|

Baptism in Belfast By Jack Deacy |

|

|

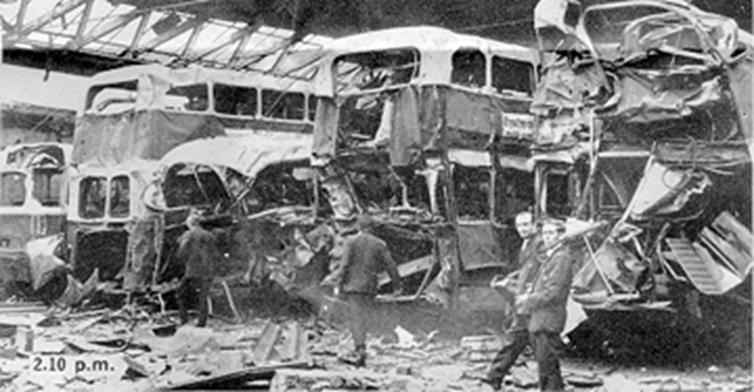

Bloody Friday, July

21, 1972, Belfast explodes as the IRA detonates a murderous sequence of 20

bombings throughout the city in a carefully orchestrated timetable of

terror. Nine people are dead, 150

injured. Above, the Smithfield Bus

Station, the first target hit. |

|

|

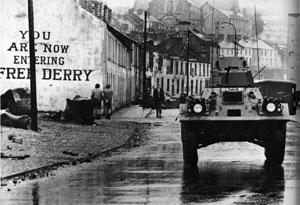

Bloody Friday, July 21, 1972, a day of carnage in Belfast,

Northern Ireland. |

Within ten days of

the attacks, British tanks move into the Bogside area of Free Derry. |

|

Baptism in Belfast By Jack Deacy

After the Northern Ireland "troubles" resumed

in 1969, journalist Jack Deacy made several trips to Belfast, reporting for

the New York Daily News, New York Magazine, the Village Voice and the Dublin

Evening Herald. In 1972 he moved to Belfast to get a closer look at the

latest round in the 400- year-old conflict between Britain and Ireland and

between the Protestant and Catholic communities in Northern Ireland. What

follows is a report on his first few days in Belfast in July 1972.

On the afternoon of July 21, 1972, I

found myself standing in

front of a modest row house in the Ballymurphy section of Belfast,

Northern Ireland. Waiting. I had spent the night there as a guest

of Seamus Drumm, an Irish Republican Army (IRA) gunman and member of

Ballymurphy's notorious A Company. Ballymurphy was a sprawling Catholic

public housing estate and IRA stronghold set on high ground overlooking Belfast's

city center. Others

soon began gathering in front of their homes. At exactly

two o’clock, the sound of an exploding car bomb in the city below carried up

the hill. A great cheer went up from the crowd. A man nearby started

counting. “That’s one,” he shouted. A few minutes later, the flat thud of

another bomb below. "That's two," the man shouted. Cheers and

applause. Over the next hour a car bomb exploded every few minutes until the

man stopped counting. A huge, low grey black cloud now engulfed the city

center. The IRA had

placed and exploded 20 car bombs within a square mile radius in Belfast. Nine

dead and more than 150 injured. Among the dead were a 14-year-old boy and his

mother. They were out shopping. Others died in the city's main bus terminal.

Absolute terror and death in a small space. The day

became known as Bloody Friday. It was my baptism in Belfast. * * *

Two days

before the Bloody Friday bombings, I linked up in Dublin with Jack McKinney,

a Philadelphia Daily News columnist and tv and radio personality in the City

of Brotherly Love. McKinney and

I had become friends and I was to take over his Belfast apartment where he

had lived for a year working on a book. Crowds of international sports

journalists and other swells were gathering in Dublin to attend the fight

between Muhammad Ali and a journeyman named Al “Blue” Lewis. A former

boxer himself, McKinney was handsome, charming, fearless, intellectual,

street smart and a risk taker of high degree.

He loved to drink and dine, tell stories and chase women. McKinney had

erudite tastes. His favorite things were boxing and opera and he was a

commentator and critic of both. And as I was soon to discover, he also believed

in getting emotionally involved in the stories he covered. He took sides. In

Northern Ireland his side was the Catholic minority. In Dublin,

he had IRA man Seamus Drumm in tow. Drumm was a fanatical boxing fan and his

hero was Muhammad Ali. In Philadelphia McKinney had become close to the

Dundee brothers, including Angelo, Ali's trainer. This gave us a free pass

into Ali's dressing room about a half hour before the fight. Ali was

stretched out on a training table, his hands folded behind his head. He was

cool and calm and talked non-stop, jumping from one subject to another.

McKinney introduced Drumm as "a real revolutionary from Northern

Ireland." Small, slight with the face of an altar boy, Drumm was not

your central casting revolutionary. When he went to shake Ali's hand, Ali did

a double take, put his hands and forearms to his face, covering up. "Don't

hurt me mister revolutionary, please don't hurt me," he said. "I'm

too pretty." They shook hands, a photo was taken and Ali wished him

well. The three of us were able to hang around long enough to hear

Ali's continuing monologue. He had a question for one of his Irish security

men. “Something

bothering me about Ireland,” Ali said. “Where you Irish hiding all the

niggers. I have not seen one since I

came here to Ireland. Where you got them?” “Oh no,” the security

man said. “We have many black peoplehere in Dublin. In fact most them are

Nigerians training to be doctors.

They're probably in class or home studying. That’s why you don’t see

them.” There was laughter all around. *

* * The following morning we were in a car

heading north to Belfast. McKinney was

driving with Drumm up front and former light heavyweight champion Jose Torres

and myself in the back. Soon after we crossed the border we ran into a

British Army security stop. McKinney rolled down his window. “Hey, any of you guys here boxing fans?” “Yes we are,” said the soldier, “In the back seat I’ve got Jose Torres,

the former light heavyweight champion of the world,” McKinney said. “How

would you like to meet him?” Several soldiers gathered around

the car. Torres got out and talked with them and posed for a photo with

each soldie Everybody was happy as goodbye

handshakes and backslaps ended the visit. We were waved through without a

search or a dog sniff. And from the front seat, the wanted IRA gunman waved

goodbye to his mortal enemies. We would learn later that the car was packed

with gelignite, an explosive used by the IRA. Even in the sunshine, Belfast was a

grim, grey city, a city now occupied by the British Army, a city of security

checkpoints, of segregated communities, a city of death, a city without a

future. It had a puritanical streak; swings for children in the parks were

padlocked on Sundays. It was a city of stunted red brick row houses

originally built for textile workers when Belfast's linen trade flourished.A

city where discrimination against the Catholic minority in housing, jobs and

education was enforced by the governing Protestant majority. And it was the

city where the doomed Titanic was built. In Belfast we drove directly to Seamus

Drumm's 'safe house' in Ballymurphy. In the living room we were

introduced to several IRA men who were lounging about drinking beer. Among them was the hard man, Jim Bryson,

the officer in charge of A Company who was a legend in the IRA for his daring

and his record for killing British soldiers. He had also led an

amazing escape from the British prison ship, the Maidstone, a year

earlier. In Ed Moloney's "A Secret History of the IRA," Bryson is

described as "a controlled psychopath with ice water in his blood"

who would "do things no sane man would even consider. His favorite

weapon was a vintage Lewis machine gun –

"Big Lewie" – with which he used to terrify British

patrols. Also in the group that

afternoon was Tommy "Toddler" Tolan who was with Bryson in the

Maidstone escape. During the afternoon an officer from the

IRA's Second Battalion – of which A Company was a part – paid a visit to the

house to reprimand the company. A few weeks before A Company members hijacked

a liquor truck so that there would be refreshment at their colleague's

wedding. "This is not how to win hearts and minds," the officer

told them. "Let's not have this carry on again." Torres was a big hit with the boys of

Company A. Belfast was a boxing town and to have a world champion among you

drinking and talking was something you only dreamed about. To show their

appreciation they invited Torres to join them in target practice in nearby

Casement Park Later that evening

McKinney and I dropped off Torres at a safe house in another part of the city

where he would be staying during his visit. On the way back to Ballymurphy,

McKinney had news for me. “Don’t be in downtown Belfast tomorrow

after one o’clock.” “Why, what’s going on?” “Because it’s going up.” “What’s going up?” “The city is going up. Belfast is going

up.”

* * * About an hour after the

bombings, McKinney let me know that we'd be spending the night at the home of

Frank Gogarty in the exclusive Fort William Park community. Gogarty, a small,

lean, handsome man of middle age, was a dentist with a practice in the rough

Protestant community called Tiger Bay. Many there referred to him as the

"IRA dentist." He was also chairman of the non-violent Northern

Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) formed in the late 1960s to

protest and reform discrimination against the Catholic community. But he was

also a staunch IRA supporter which led some to believe that he was

diverting money raised by NICRA for humanitarian aid to the IRA to buy guns

and ammunition. When we pulled into the driveway of the

Gogarty's beautiful old three story Victorian, an angry crowd from a nearby

Protestant public housing estate was beginning to gather in the street in

front of the home. They greeted McKinney and I with a shower of rocks and

cries of "Fenian bastards." In a lounge area off the kitchen, I met

Gogarty, his attractive French born wife, and four of their six sons. Mrs.

Gogarty had been weeping . Alongside her sat an elderly French couple

who had come to Belfast on an ecclesiastical "mission of

peace." The man was a Protestant minister who a half hour earlier

had been attacked and roughed by the same Protestant mob that

hurled rocks at us. Irony knows no bounds in Belfast. Also in the lounge were

several others who I had not been introduced to but would soon get to know

when the sun went down. The evening news was on and we all

watched in silence. There were grim scenes of firemen and

policemen shoveling up body parts after the bombings. The silence

was a sign that many IRA supporters were appalled by the horror of the act.

We were served sandwiches and tea and whiskey. I certainly needed the

whiskey. By this time it was apparent that Gogarty had already taken too much

drink. As night fell, the angry crowd outside

grew louder and larger. They were enraged by the day's events. The IRA

dentist would have to pay a price. And so would his guests. McKinney took

charge. The front door was reinforced with lumber and furniture. The house's huge windows began to be taped.

Mrs. Gogarty and her French peace friends went upstairs to the third floor. Rakes, hatchets, pikes, shovels and

pitchforks were handed out. Around 9:30 the crowd charged the house. I was in front of a window with a pitchfork

as the crowd smashed the windows, threw rocks. A few attempted to come

through the windows but withdrew. They were probably as terrified as I was.

The windows of cars had been smashed and one car overturned. The front door

had held. During the lull, McKinney asked me to

try to get someone on the phone who could get the RUC or the Army to respond.

In the phone book I got the office number of the U.S. Consul in Belfast.

Miraculously, someone answered the phone and I explained that I was a

journalist and an American citizen and the house I was in was under attack by

a mob. I was put through to the Consul who was an African American fellow. I

explained the urgency of the situation and pleaded with him to call the Army

and the RUC and demand that they respond. "First of all, Mr. Deacy, remain

calm," he said. "Secondly, ."I would advise that you leave the

house as soon as you can." "I can’t leave the house. It's

under attack by a mob of Protestants. For Christ sake, call someone." "Mr. Deacy, unfortunately, the U.S.

Consul doesn't carry much weight here in Belfast. But I will do what I

can." The mob now had flaming torches. They

charged again and several of the torches landed in the house but were quickly

extinguished. I told McKinney that if they had Molotov cocktails or guns or

both we were dead meat. Over the next hour, the mob charged twice more. But

no Molotov cocktails. No guns. Now I thought I might live. About 11:30 the

RUC arrived. We could see that an officer was talking with a few mob members.

He walked slowly, hands clasped behind his back, to the front door.

McKinney let the officer in. "Here's the situation," he

said. "Some of their leaders are convinced that there are guns in the

house." "If there were guns in the

house we would have used them to defend ourselves," McKinney said. "The leaders say that if two of

them can join me in a quick walk through the house, then they will

disperse." After some back and forth, a deal

was struck. One mob leader would do a walk through with McKinney and the RUC

officer. When Gogarty, now in the lounge

drinking, heard what was proposed, he bounded down the hall and went for

McKinney. "Don't let those bastards into my house," he roared.

They'll map every room in every part of the house. And then they'll come back

and break in and kill me and my family." I was able to restrain Gogarty and get

him back into the kitchen. The house tour took place, the crowd

dispersed, an RUC squad was posted. McKinney, against all advice,

got into his windowless car, drove to Ballymurphy and brought Seamus Drumm

and another IRA man back to Gogarty’s. They each carried a modern Armalite

rifle and were to spend the night as our protectors. Just in case. I shared a room upstairs with Seamus

Drumm while the other gunman was in the lounge with McKinney and others.

A few hours later a shot rang out downstairs. Drumm was up in a second and

started quietly down the stairs. I

waited by the stairs. As it turned

out, the other gunman had broken down his Armalite rifle for McKinney. In

putting it back together, a round discharged, missing Gogarty’s son’s head by

just a few feet. On that lucky note, our long night’s

journey at Mr. Gogarty’s house came to an end. * * * I

spent another seven months in Belfast. It was to be the bloodiest year in the

30 year struggle in the North. I thought if I got close to it, I would

understand it. The opposite turned out to be true. On a rain soaked

Thursday afternoon in early 1973, I drove out of grim, grey Belfast for the

last time. I had left my romantic notions behind. I did not return to the

city for 30 years. The look of panic I saw on the faces of people near the

World Trade Center on September 11 was the same look I had seen on the faces

of people in Belfast in 1972. That look convinced me to return. When I did, I did not recognize the city.

It had been scrubbed clean, the Army was nowhere to be seen and there

was a fine spirit among people on the streets. Peace was at hand. Belfast was again a city of life. |

|