|

A Sports Writer Looks Back – and Back By Ira Berkow |

|

|

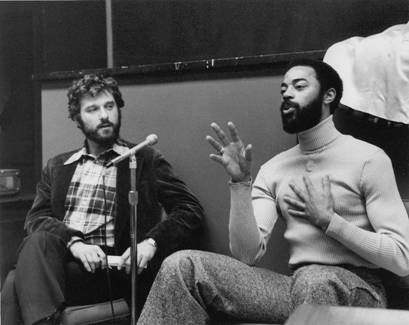

Ira

Berkow with Walt Frazier, star guard for the New York Knicks, with whom he

would go one-on-one at his summer basketball camp in the Catskills, 1976. |

Berkow’s pals. |

|

By Ira Berkow Yes,

it’s true, as many believe, working for The New York Times has distinct

advantages for a writer. One day, for example, in the 1980s, I was in the

Yankee clubhouse talking with Dave Righetti, the left-handed pitcher. I had a

good working relationship with Righetti, having done a story on him when he

was in the minor leagues, which established a kind of rapport between us. I

pulled up a chair and chatted with him, and then asked him a question, which

I don’t now remember. “If

I give you the answer,” he said, “the guys here will read it and they’ll get

pissed off.” There

was a silence. “Hell,

I’ll tell you,” he said, looking around the clubhouse. “These guys don’t read

The New York Times.” Which

reminds me of another Yankee pitcher, and another question – and answer. Goose

Gossage was one of the most feared pitchers in baseball, with a wicked

handlebar mustache and an even more wicked fast ball. In the clubhouse,

again, I said to him, “Goose, everybody’s afraid of you. Who are you afraid

of?” He

thought for a moment. “New York waiters,” he said. And

sometimes you may have to risk your pose of professionalism for a proper

cause, such as pleasing a couple of kids. I refer to a time in 1971 when I was

about to go to Chicago to interview Muhammad Ali, in training for a

heavyweight title fight with Jimmy Ellis. Before leaving New York I ran into

a woman I knew and told her what I was planning. “Oh, could you get an

autograph for my two boys?” she said. “They’re such big fans of Ali.” “No,”

I said, “it’s not professional. I can’t ask a subject I’m writing about to

give me an autograph.” “Oh

please,” she said. “The kids would love it!” “Well,”

I said, “if the occasion arises, maybe. But don’t count on it.” Soon

after, I spent a day with Ali, and at day’s end I said, “Champ, I hate to do

this, but would you mind signing an autograph for two small boys?” “No

problem,” he said. I handed him my note pad and pen. He asked the boys’

names. I told him and, for some reason, added, “Their mother has trouble

making them clean their room.” He

wrote: “To Timmy and Ricky, from Muhammad Ali, Clean that room or I will seal

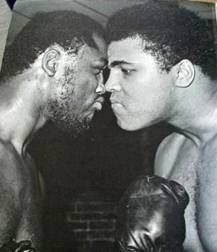

your doom.” A

year or so later, I was with Ali’s arch rival, Joe Frazier. I decided to ask

him for an autograph for the same two boys, just to see how he would handle

it, and told him the same thing about their mother’s problem with their

housekeeping. He

said, “If their mother didn’t have trouble making them clean their room they

wouldn’t be boys.” And then he signed, “Best wishes.” That was all. But to me

it said so much about the two personalities, Ali and Frazier. Both were dead

on, by their own distinctive lights – Ali and his creative “Rope-a-Dope”

style, Frazier barreling forward and “smokin’.” One

of the pleasures of being a sportswriter for the last 42 years – at the

Minneapolis Tribune, for the national feature syndicate Newspaper Enterprise

Association and, for the last 26 years, at The New York Times – are the

people you meet (such as those mentioned above) and the places you go and the

events you attend. I covered the 1972 Munich Olympics, the 1989 earthquake

World Series, the spine-tingling 1991 Super Bowl in which the Giants won,

20-19, as well as the hospitalization at Walter Reed of a former star Notre

Dame basketball player who had her left hand shot off in the Iraq war – her

shooting hand, no less, and the one with her wedding ring (the hand was later

recovered and the ring returned to her). I

also had the opportunity to play pickup basketball with Oscar Robertson at

the Y lunchtime games in Cincinnati (the Big O still had his deft shooting

touch at age 58), go one-on-one with Walt Frazier in his prime at his summer

basketball camp in the Catskills (remarkable how much he grew in front of me

as he got more and more serious, and I got smaller and smaller), was at the

other end of a Rod Laver serve during his practice session (the ball happened

to hit my racket, like a brick, and nearly broke my wrist), faced Cy

Young-award winner Denny McLain in a pickup game in Lakeland, Fla., when he

was getting back into shape after his 1970 suspension from the Detroit Tigers

(I was amazed at how well he concealed the pitch until it seemed it was

nearly on top of me, before fanning), and once offered to spar a round with

Joe Frazier (just to experience what it’s like being in the ring with a

heavyweight champ), when he was at the Concord Hotel training for a title

fight against Buster Mathis. Frazier, as it might be recalled, had a left

hook like a wrecking ball. “Did

you ever box?” asked his white-haired trainer, Yank Durham. “Growing

up in Chicago there was a gym in the local police station where we kids would

fool around,” I replied. “Are

you in shape?” “I

ride my bicycle around the Village, where I live, a few times a week.” “Hmm,”

said Durham. “Okay. Then my man will only break two or three of your ribs.

You see, the Champ, he don’t know how to play.” “Hmm,”

I replied. “I think, Yank, that I’ll take a rain check.” The

sports department has sometimes been referred to as “The toy department” of

the newspaper. Perhaps at least since Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier

in the major leagues; surely after newspaper reporters and editors discovered

that they were often printing the lies of the brass and the administration

during the Vietnam War, and then during the Watergate scandal when again

newspapers were slow to understand that the Constitution was being subverted

by Nixon and his cohorts, all of this influenced how even sports were being

reported with greater depth and insight and investigation. The

sports department was indeed a part of the rest of the paper. And the

responsibilities that were incumbent on city-side reporters, and the

Washington press corps, for two examples, to get the story, and get it right,

arrived at the door step of the sports departments. And less and less, it

seemed, were we living the adage of Chief Justice Earl Warren who said “I

always turn to the sports pages first, which records people’s

accomplishments. The front page has nothing but man’s failure.” We are still

recording “accomplishments ” – David Cone pitches a perfect game, or a Nadia

Comaneci scores a gymnastic 10, or Vinatieri kicks a 48-yard field goal with

no time left on the clock to win a Super Bowl – but “man’s failure” has

increased in coverage. Did Bonds use

steroids to break home-run records? Did he perjure in grand-jury testimony?

Why can’t women play golf at the august site of the Masters? Why aren’t there

more black coaches in college football ranks? Were the Duke lacrosse players

rapists or falsely accused? The front page is now not the only province for

these stories, but often that front-page story is covered by a sports

reporter. Along

these lines, one of my most satisfying stories took place after the

earthquake in San Francisco, which occurred just before the third game of the

World Series there. Bridges collapsed, buildings toppled, fires raged. San

Francisco lost its electricity for a short while and went dark at night,

citizens brought out home-made flares to light up intersections. The Series

was delayed 10 days. The several Times reporters on the scene were asked to

cover the earthquake. One of my assignments was to find a hero. On a fall

October morning, amid much devastation on the streets, I asked around, and

around. Someone

mentioned a firefighter who had saved a woman in a burning building. The

informant didn’t know the firefighter’s name, or his fire company. I kept

asking around, and found out. His name was Gerry Shannon, age 44, and a

veteran of 19 years as a firefighter. He was assigned to Hook and Ladder

Engine No. 9, and was asleep when I got to his station house. He awoke to

come downstairs to talk to me. It

happened only hours after the earthquake hit at 5:04 p.m., Pacific time.

Shannon and his fellow firefighters were battling blazes along Beach Street,

near the Bay. He heard a moan from a collapsed house. It was a woman. When

the earthquake struck, she was on the second floor. The floor had opened like

a trapdoor, and she tumbled down, the rest of the building crashing down

around her. Her

name, as he later learned, was Sherra Cox, a 55-year-old woman, and she lay

trapped under a door and a doorjamb for what seemed an eternity to her. She

smelled fire – the buildings around her were aflame – and felt the creaking

of wood. She feared she might be burned or crushed to death. She told

herself, “Don’t panic.” She prayed, and tapped, hoping someone would hear. Shannon

heard the tapping sound from within the rubble of the house. He instinctively

crawled through a dark space and began to dig his way toward the tapping. He

yelled, “Where are you? Where are you?” He

heard a woman’s voice, “I’m here! I’m here!” He

found that a wooden beam from the doorway had fallen across her body and

that, by incredible good fortune, it had kept the rest of the building from

burying her alive. All

around outside, sirens whirred, shouts were heard, but Shannon listened only

for the woman’s voice. The space was too small for him to maneuver with his

fireman’s helmet and turnout coat, so he removed them. Now, in blue T-shirt,

he crawled through the debris and rubble, skinning his arms and knees as he

clawed and wriggled through. After about 30 minutes he got to her. He was

able to reach out and touch her. “She grabbed my fingers,” Shannon recalled,

“and it was so tight I didn’t think I could get loose.” He

told her, “I’ve got to go back for equipment.” “Don’t

leave me,” she said. “Don’t leave me. I don’t want to die here.” He

explained that he had to get a saw to cut through the wood beams. “Promise

you’ll come back,” she said. “I

promise,” he said. Shannon

retreated on hands and knees, knowing he didn’t have much time, got the equipment and hurried back. He sawed through one

beam, had trouble with another– “I thought, `We might not make it’” – used a

hatchet to that one, and pulled Sherra Cox from the building, and, in the

glow of fires, helped her onto a stretcher on the street. I

wrote this exclusive story, of this remarkable man and the storybook rescue,

and it drew national attention. When

the Series resumed, 10 people were picked as “heroes” of the earthquake to

throw out the first ball for Game 3. Gerry

Shannon, in civilian clothes, was one of those true heroes, taking his place

close to the mound, as even our “baseball heroes” in the dugout applauded. As

I watched, I thought, “I know Gerry Shannon,” and, as hard-boiled a reporter

as I purport to be, a tear came to my eye. ________________________________________ Pulitzer Prize-winner Ira

Berkow, retired from the New York Times on February 1, where he had been a

Sports of the Times columnist and feature writer since 1981. He is the author

of 17 books, most recently the memoir “Full Swing: Hits, Runs and Errors in a

Writer’s Life,” published last April. |

|