|

By |

||

|

|

||

|

By “Surely God must have been with me

when I picked Jackie,” Branch Rickey said after he looked back at his

unprecedented signing of Jackie Robinson to a baseball contract in 1947. When Robinson died in 1972 of

diabetes and hypertension, some white sports columnists wrote that his coming

was no big thing and would have happened sooner or later. Others, more cynical, described Rickey’s

motive as greed. But the fact is that

before Rickey no one had done it or even seriously proposed doing it. That’s his legacy. And I guess it’s mine too since when

I received a publisher’s contract to write a biography of Rickey, I knew I

had to find out why so believing and trusting a Christian conservative and

Republican supporter of Cold War policies would dare to change the game he

revered forever. Very quickly I

understood the central role his religious faith played. And for most of his post-Jackie life he

peppered his speeches with references to the absence of fairness and justice

for Black people and other minorities. “Why is there an epidemic of racism

in the world today,” he began a talk on one steamy summer day in the late

fifties in I was born in Actually, we lived a myth, namely

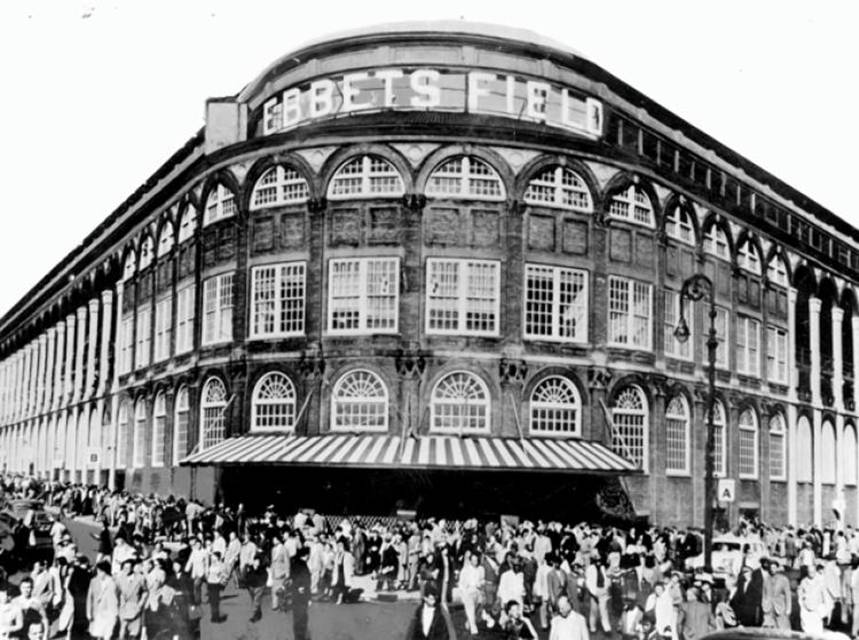

that Until then, Ebbets

Field was my cathedral and passion for the Dodgers my faith. One thing about Rickey was that he

understood the extraordinary hold the team had on its fans. When he was forced out by Walter O’Malley –

he who kidnapped the team and fled to LA (Old joke: An armed “They were wonderful years. A community of over three million people,

proud, hurt, jealous, seeking geographical, social, emotional status as a city

apart and alone and sufficient. One

could not live for eight years in He was referring to a tradition where

speed and technology could never quite supplant his ingrained 19th century

deep-seated belief that baseball, and the profound city loyalties it

fostered, symbolized continuity in a world fractured by irreparable

disruption and unforgivable high crimes.

How, he once asked in a speech, can anyone explain the murders of one

and a half million Jewish children by the Nazis and their allies? In 1936 I saw my first Brooklyn

Dodger game with my Hebrew school class, shepherded by our rabbi’s brother,

sadly a Yankee fan. Bucky Walters, a Philly third baseman converted into a

pitcher with a windmill motion faced my favorite, Fred Frankhouse,

the idol of By the next year or so, with money I

had earned as a delivery boy for a delicatessen and a garment center company,

and regularly fortified with a sandwich and banana provided by my mother who

had somehow begun to understand what baseball meant to me, I took the subway

to Ebbets Field and sat alone in the bleachers. I’ve never forgotten certain special

players now ancient history like Gene Hermanski,

the first Dodger to welcome Robinson and whose photo appears with Rickey on

the cover of my hardcover book and who tried unsuccessfully to get all the

players to wear Robinson’s number 42 because of threats against his

life; slugger and Hall of Famer Joe Medwick who came from

the Cardinals in a trade pushed by cheapskate Cardinal owner Sam Breadon and executed by cheapskate Cardinal GM Branch

Rickey and was promptly accidentally beamed by Cardinal pitcher Bob

Bowman; third baseman Joe Stripp, dubbed without imagination by a sportswriter

“Jersey Joe” because he came from New Jersey and whose major contribution was

being traded for four players for Durocher; catcher Babe Phelps who was afraid to fly

and preferred trains and buses; Luis Olmo, the team’s first Puerto Rican position player; Ralph Branca, who

surrendered the infamous homerun to the Giant’s Bobby Thomson in 1951 (the

Giants stole the Dodger catcher’s signal by telescope, as the Wall Street

Journal reported a half century later), and was an early supporter of Jackie

Robinson; Canadian outfielder Goody

Rosen and Brooklyn-born pitcher Harry Eisenstat, my

favorite Jewish players (there weren’t many but Branca

later revealed he had a Jewish mother)

and Chris Hartje, an obscure backup catcher

in 1939, who hit a double before leaving baseball forever, drafted into the

Army preparing for WWII. To keep up on all their doings I was

a voracious reader of two gossip scandal-drenched and loud-mouthed tabloids,

the NY Daily News owned by the New Deal and FDR-hating Joseph Medill Patterson, and the other Hearst’s Daily Mirror,

sketchy and shallow, which featured Walter Winchell,

who I admired until he became Joe McCarthy’s ugly echo. Both papers though were blessed with

opinionated columnists, as did the Brooklyn Eagle, which to its everlasting

credit hired Walt Whitman for a two-year stint as its editor in 1846. When the Dodgers won the pennant for

the first time in twenty years in 1941, the Eagle spread a 12 pt. “WE WIN” across Page One

and Peewee Rosen and I played hooky to cheer on the players as they were

driven by in open cars in downtown And then there was the Daily Worker,

perpetually blind to Stalin’s monstrous crimes while falsely claiming that

its Party and sportswriters had played an important role in persuading Rickey

to sign Robinson. That Rickey, an

inveterate anti-Communist and Cold Warrior, paid any attention to Communists

is not believable and there is no evidence that he ever listened to

them. Then, too, he would never have

accepted what a non-Communist writer, the late leftist Jules Tygiel, erroneously wrote, namely that the Party and

especially the Daily Worker “had played a major role in elevating the issue

of baseball’s racial policies to the level of public consciousness,” a deeply

flawed conclusion with little or no supporting confirmation. In my opinion, the best article on

the subject disputing Tygiel’s inaccurate judgment

remains Henry D. Fetter’s definitive study, “The Party Line and the Color

Line: The American Communist Party and

the Daily Worker and Jackie Robinson,” which puts the alleged contribution of

the Communists to rest. In truth, as I

also found long before, l was that Rickey’s faith-driven dream and Robinson’s

great courage led the way to the historic end of racial segregation in

baseball. My baseball. A bucolic gamer, endless and timeless. Slow, unchangeable and reactionary, even as

it struggles nowadays to absorb the challenge of analytics and sabermetrics. I

know: It’s excessively commercial,

subservient to corporate control, silent about pointless American wars and

gravely harmed by an inexcusable imbalance between thew

haves and have-nots. I know, I

know. But it’s still baseball, my

baseball. And now, it’s my Mets too. |