|

Stan Brooks: Radio

Newsman On the Move By Eve Berliner |

|

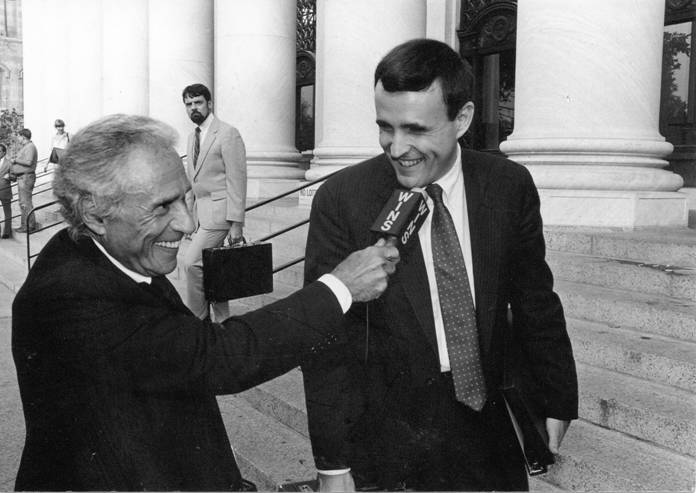

1010 WINS Senior Correspondent, Stan

Brooks, with then U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York,

Rudolph Giuliani, on the steps of the Federal Courthouse in Foley Square, New

York City, 1988. |

|

By Eve Berliner He’s the voice of the city,

on the move, a part of its pulse, its passion, its tragedies great and small,

ace radio newsman Stan Brooks for over 40 years a part of the city’s very

insides. He was a child of the

Bronx, small and shy, 182nd Street and Walton Avenue home ground, played

in the streets, stickball, hockey (on roller skates), marbles, urban baseball

(against the walls) and for a 13th or 14th birthday,

was given a fortuitous little printing press out of which was born “The

Walton Avenue News,” the inception of his journalistic career. He listened to Uncle Don

and the old radio serial shows, his favorite, NBC’s stentorian-voiced Kenneth

Banghart. His real interest was in the

newspapers that his father would bring home with him each evening: The New York Post, The Journal American,

PM, Compass, Star. He wrote for his high

school newspaper, “The Clinton News”[DeWitt Clinton H.S.], a general news

column entitled, “Babbling Brooks,” which he presented in a Walter Winchell

staccato of dots, dashes and bulletins. His heroes were Lou

Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, the Brooklyn Dodgers and his brother, Alan Brooks,

sports editor of “The Heights Daily

News” at NYU, his inspiration, [now a doctor]. In later years, it would

be the great New York Times reporter Meyer Berger who commanded his high

respect. (“He would dance on tables.”) And then, there was the

trombone (add Tommy Dorsey to that list of idols) which now sits on a stand

in his bedroom, a gift from his three sons who had it repaired, repolished

and relacquered, sitting ready, in suspended animation, for his not imminent retirement when he plans to

seriously return to its study. Brooks had been drafted

out of City College into the Infantry in 1945 landing him overseas post-World War II as a trombonist in a

dance band entertaining the troops in Hawaii!

The aspiring trombonist returned to the states, graduated from Syracuse University and became a reporter and

editor at Newsday for the next 11 years.

His son George, a virtuoso jazz saxophonist, took up the mantle of

music. They were the rock ‘n

roll days of the sixties, 1010 WINS, home of the Top 40 and Murray the K, a

godlike figure known as the 5th Beatle; three big rock stations on the

airwaves: WINS, WABC and WMCA, The

Good Guys, Stan Brooks at the helm as director of news at WINS: “Westinghouse had a

serious commitment to news but disk jockeys like Murray the K didn’t want any news. The December 1962 newspaper strike that

lasted 114 days changed all that. We beefed

up news – ½ hour at 5:30 every evening, the usual 2½ minutes on the hour

raised to five, five minutes on the half hour expanded to ten.” It was the brainchild of

Joel Chaseman, vice president and general manager of WINS, subsidiary of Westinghouse Broadcasting. The

idea had been germinating in his mind for some time. Clandestinely, he came

down to Stan’s office late in 1964. “How about going

all-news?” he asked. “What’s all-news?”

responded Brooks. “I was sworn to secrecy,

a real cloak and dagger kind of situation.

He and I were the only people at the station who knew about this. Didn’t want the disk jockeys to know, the

outside world. One of the networks

might get the early jump on us. It was

a top secret operation.” Brooks surreptitiously

journeyed by train to Philadelphia, Chicago, Minneapolis, St. Louis,

searching for talent, listening to “the morning rush,” amassing a staff of

broadcasters and engineers and formulating a plan for the station: its format, its conception, its

content. It would be a revolution in

news, the immediacy of breaking stories as it happened 24-hours-a day, man in

the street interviews, people who talk like New Yorkers talk, keep the

station sounding like New York. The station signed off

on April 18th as a music

station at 5:30 in the evening and reawakened the next morning as the first

major all-news radio station in the nation:

April 19, 1965. It was the Great

Northeast Blackout of ‘65 that put it on the map and secured its place in history``0.. WINS was the only radio station to stay on

the air. An engineer had managed to

hook up the phone line directly to a transmitter in New Jersey. The studio, on the 19th

floor of 90 Park Avenue, had no lights, no electricity; they worked by candlelight. “Everything had to be

live. You couldn’t record anything. There was no power. Reporters had to go

down 19 flights to get the story and then walk up 19 flights to go on the

air. They did it all night long. Then stations began calling up from all

over. ‘Give us feed on the

blackout. Ready 3…2…1…’ “New York City

was plunged into darkness …” adlibbed Brooks in a night of frenzy to

remember. Six weeks later Mike

Quill took the Transit Workers out on strike, bringing to a halt all subway

and bus service for the subsequent 12 days, the city paralyzed and weary, an

ominous beginning for the mayoralty of John V. Lindsay. WINS became for New

Yorkers the crucial voice in the crisis and even helped facilitate a

settlement by acting as a kind of mediator between Quill and his arch foe

“Lindsley,” both utilizing the air waves to send messages to one another. He has covered the most

significant stories of our time: The

civil rights crises, the Watts riots, the William Calley trial of My Lai

infamy, Chappaquiddick, the turbulent

Vietnam War demonstrations of the 60’s when he was tear-gassed outside the

Justice Department after a tumultuous rally on the Washington mall, the

Chicago Democratic Convention of 1968, the bloodbath on the streets, Malcolm

X’s funeral, the Clay Shaw/JFK assassination trial, Hurricane Camille, the

Swiss America plane crash at Peggy’s Cove, Newfoundland, (he was there on

vacation, first reporter on the scene), the crash of TWA Flight 800, Cape

Canaveral, 1967, when Gus Grissom and two other astronauts were killed on the

launch pad in a raging fire – and his six day trip to Saudi Arabia in the

initial days of Desert Storm to cover the Harlem Hell Fighters, National

Guardsmen from the 142nd St. Armory in New York. But it was Attica that

was the most wrenching, the uprising, siege and slaughter inside Attica

Correctional Facility which began on September 9, 1971 and ended four days

later in a barrage of gunfire by New York State Police that left 29 inmates

and 18 hostages dead with 89 wounded, the final storming of the prison at the

behest Governor Nelson Rockefeller after days of tense and unrelenting, but

hopeful, negotiation. “Attica was the most

emotional for several reasons. I was

there for five days outside the prison wall, 4 hours sleep a night, 15/16

hour days. Flew up 12:30 on the first day.

Didn’t leave until 2:30 the next morning. Up again at 5 or 6. The families of both guards and prisoners

gathered at the gates. The prisoners all black and Hispanic from the area,

the guards all white country boys, farm boys from Attica and Batavia. Rumor had it that guards were being held at

knife point and that one had had his throat slashed but it turned out not to

be true. I could feel for

everybody. I wanted to cry for these

people.” “9/11, of course, was

emotional in a different way, stunning, startling, horrific.” Blockaded at Foley

Square by cops who prohibited him from moving closer to the catastrophic

scene, he would witness the exodus of thousands of people from Ground Zero,

the distraught evacuees covered with ash, the firetrucks racing up the

streets spewing the stuff, trucks with searchlights going in, finally finding

a working telephone in a Chinese laundry behind the courthouse, his wife Lynn

frantic as she fled the Municipal Building where she worked, headed uptown

toward home, running into an electronics store in the Village to purchase a

radio, her heart beating profusely until she heard her husband’s voice and

knew he was alive. Through it all, his love

for his work. Stan Brooks, 78 years

of age, a cub reporter at heart, full of energy and radiance, always

searching for the next great story as he oversees the procession of mayors

from Beame to Koch to Dinkins to Giuliani to Bloomberg, from his cat’s eye

vantage point in City Hall. “I have no idea what

each day brings,” Stan Brooks notes quietly, “My life is not my own. Wherever they send me, whatever they want

to do with my body,” he laughs. |