|

Al Campanis: Exiled from Baseball Was Justice Done? By |

|

|

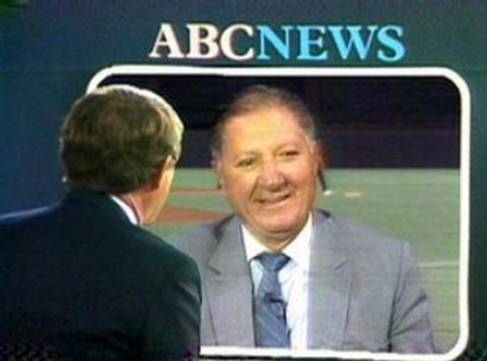

Al Campanis, fired on

April 6, 1987 as general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers for controversial

racial remarks concerning blacks in baseball, during an interview with Ted

Koppel on the late night program, “Nightline.” |

Campanis had a brief major

league career as second baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers and the minor league

Montreal Royals, before becoming a scout for the LA Dodgers and rising to

general manager. |

|

By Murray Polner I often think of Al Campanis, a true baseball

old-timer I knew, who was drummed out of the game he so loved in 1987 because

of his foolish remark on the television program, “Nightline,” about black

players lacking “the necessities” to be managers or front office

executives. He’d been a Montreal Royal

shortstop in 1946 playing alongside Jackie Robinson at second base, barnstormed

off-season with a racially integrated squad, a Brooklyn Dodger scout who

unearthed Roberto Clemente and Sandy Kourfax, and who reached the apex of his

profession as General Manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers and took them to

four pennants and one World Series title. He even prevented a former black

Dodger from killing himself. And then he was suddenly, abruptly,

unexpectedly, and permanently blacklisted. In late 1987 or early 1988 Al Campanis

phoned. Out of a job since that TV performance,

he asked if I would help him write his autobiography. He had come to me, he

said, because I’d written a biography of his former mentor and boss Branch

Rickey. The next week I drove up the coast from Laguna Hills to Fullerton in

Orange County in southern California where Al and his wife lived in a modest

suburban home not far from Angels Stadium. Born out of wedlock in 1916 in Kos, part of the

Dodecanese Islands (once part of Italy but returned to Greece in 1947)

Campanis and his mother arrived in the U.S. when he was six. He graduated New

York University, played football there though loved baseball more, and then

joined the Navy. Once discharged, he

began playing minor league baseball. On at least

four or five occasions I drove north to Fullerton, where Al and other

expatriate former Brooklyn Dodgers had moved in 1957 when Walter O’Malley

kidnapped the team and moved to L.A.

(As the hoary joke among unrequited Brooklyn fans went and still goes,

a diehard Brooklyn fan walks into a bar with a gun and sees Hitler, Stalin

and O’Malley. Guess who he shoots?). We talked and talked, drank coffee, ate sandwiches

and sat around his comfortable but hardly luxurious kitchen, his wife always

gone for the day. He was about 71, tall, agile, a still-vigorous, handsome,

if aging athlete with a commanding tone. A man accustomed to lead, or so I

thought when I first met him. He spoke quietly of his past, how Rickey taught

him how to evaluate baseball players and the skills needed to build a

successful ballclub. He was especially proud of a small book he had composed

detailing what he had learned and practiced, The Dodger Way to Play Baseball,

and autographed a copy for me and offered me as well a signed photo of

himself. Looking back, I felt like a

cub reporter, honored to be treated as an equal, a feeling which gradually

left me the more we met and talked. Soon, I could see the man was badly hurt. On other days he was more relaxed, warmer, less

interested in impressing me. He wanted

an honest book, he said, one that told his life story good and bad. He

proudly spoke of players, some black, he had treated fairly and honorably,

like Roy Campanella and of course Robinson, who he taught various infield

skills while playing together for the Dodger’s top farm club Montreal in the

International League. And he spoke of

how a deeply depressed John Roseboro, once a star catcher for the Dodgers,

tried to commit suicide in his office when Campanis persuaded him to drop his

gun. It was as if he was asking, desperately,how can anyone call me a racist

bigot? He was unhappy and wounded, profoundly regretful,

and thoroughly crushed. “Even prisoners get parole or probation, don’t they?”

he blurted out one day, managing a feeble smile. What was most difficult for him was that he

had mindlessly squandered what he treasured most in life: authority,

companionship, responsibility, The seasonal Chase. Baseball. He told me that soon after the “Nightline”

debacle he appealed to Rachel Robinson for advice and she wisely, compassionately,

told him, “Forget it, Al. Move on with your life.” In all our meetings he always returned to that

late-night TV show in the Houston Astrodome, where he expected to join Don

Newcombe, the black ex- pitcher -- who never appeared because his flight had

been cancelled due to bad weather-- Roger Kahn of Boys of Summer fame, and

Rachel Robinson to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the

significance of her husband’s arrival and impact. While he was waiting, he

told me over and again, he kept staring into the dark screen of a camera, far

from the producer in New York and interviewer Ted Koppel in Maryland. And then it came: Koppel finally lobbed him a

softball asking why there were virtually no black managers, front office

executives, or owners, and whether racial bias was widespread in baseball.

His convoluted answer would follow him into his grave. “No, I don’t believe

it’s prejudice. I truly believe that they may not have some of the

necessities to be, let’s say, a field manager, or perhaps a general manager.” Al tried to explain to me how he only intended to

refer to their lack of experience. But managers have been employed without

experience and some teams preferred hiring from an all-white, old boys list

of pals. Nor did he consider the power

of wealthy white owners, “Jock sniffers” in Robert Lipsyte’s felicitous

phrase, who had often inherited or married into money and power. He was certainly unaware of what Rev. Billy

Kyles, a close ally of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., meant when he told Tim

Wendel in Summer of ‘68 that King and

his best friends closely watched sports with “an historical eye.” In our final meeting he told me he was initially

blindsided by the question and became confused and unable to respond

sensibly. No, he hadn’t been drinking though he may have been feeling sickly.

And no, Ted Koppel had not been

unfair. In parting that last day, I left believing that despite his foolish

remark he was a good and honorable man who had been badly treated by the

unforgiving world of professional baseball and our myopic moral guardians. For saying what he did he had to resign and would

never again be hired to run a baseball team (nor, for that matter, would the

brainy, courageous Robinson after he retired) despite accolades from black

players, managers and others who knew him.

Dusty Baker, the African American manager and former Dodger

outfielder, said, "You hate that any man's career is ruined in a couple

of minutes. What he said was wrong, but he was always cool to minorities when

I was there, especially the Latin players, and the blacks.” Harry Edwards, a sociologist at Berkeley

and a civil rights activist who was taken on by baseball to help develop ways

of adding more minorities to leadership roles, worked with Campanis after

“Nightline.” On ESPN’s “Outside the

Lines” documentary he explained, “It wasn’t a simple case of Al being a

bigot—to say he was just a bigot is simply wrong—people are more complex than

that. To a certain extent, it was the culture Al was involved with. To a

certain extent, it was a comfort with that culture. And at another level, it

was a form of discourse he was embedded in.” It’s an old American temptation. Punish the words, not the deeds. Don Imus,

Andy Rooney, Jesse Jackson and Rush Limbaugh spring to mind. Some like Imus

and Rooney didn’t suffer too much and managed to recover. Jesse Jackson and

his “Hymietown” remark faded and he’s carried on in Washington. Rush Limbaugh lost lots of advertisers

(temporarily) while keeping his many radio outlets and millions of loyal

fans. And according to Larry Elder in Jewish World Review, even Harry Truman

once called New York “Kiketown” in his correspondence. Richard Nixon couldn’t

stand Jews – except, maybe, Henry Kissinger – and told his tape recorder all

about it, but he survived his foul mouth and anti-Semitism – Watergate and his resignation is another

matter. So I ask fifteen years after his death:

Should Al Campanis have been pilloried

and permanently blacklisted for one blunder? Or did white fear of being

branded bigots allow groupthink to take over?

In 1987, five managers and eight general managers or team presidents

were hired, none of them black. Someone had to shoulder the blame for

institutionalized racism. Al Campanis was the perfect scapegoat. He died in 1998, but his life was over in 1987.

His punishment never fit the crime. He should have been suspended and then

allowed to return to work. Baseball owes him a belated apology. His autobiography was never written. ______________________________ Editor’s Note: Murray Polner is

the author of “Branch Rickey: A

Biography” |

|