|

Judith Crist: Queen

Mother of Critics ‘Love with a Fanatic’s Passion’ By Eve Berliner |

|

|

“The critics who love are the

severe ones. We know our relationship

must be based on honesty.” – Judith Crist |

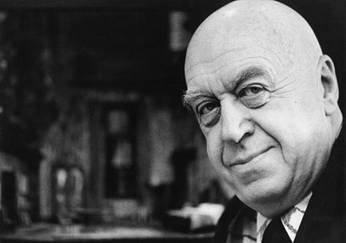

The director Otto Preminger,

notorious for his tyranny and his temper.

Twentieth Century Fox Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton

whose scandalous love affair created a worldwide senation during the making

of Cleopatra. |

|

By Eve Berliner She was the queen mother

of critics, her pen mightier than the sword in those critical years of the 1960’s

and 70’s, in the torrent of the cinematic revolution, her search for truth

fearsome and provocative. There is a fragility to

her now, at age 85, Judith Crist‘s startling blue eyes grown intense and

sentimental with memories of a life in film. It began in the depths

of the great movie palaces of her youth, her inner magical life, entranced

the first time her mother took her to the movies, the moving clouds and stars

in the palace sky, “Judy, Judy, sit down.

You look over here at the

screen,” uttered her mother. Her first real film

memory, vivid to this day, is The Gold

Rush, “Chaplin performing the ballet dance with fork and rolls, eating

his shoelaces as if they were spaghetti, tipping the cabin at the edge of the

precipice!” The rush was indeed unforgettable. She fell in love with

the movies with a fanatic’s passion.

It became her secret life, sneaking nickels and dimes from her

mother’s purse in high school, cutting classes irreverently and joyously at Her early inspirations

were the distinguished critic James Agee who wrote for “The Nation” and Frank

Nugent of The New York Times. The power of the

critic? “Not much. It’s mainly for the edification and delight

of other critics and cinephiles.” She was known as “the

critic most hated by “The most glorious

epithet ever hurled at me appeared in Time Magazine, anonymously: ‘Snide, sarcastic, supercilious bitch!’” Otto Preminger labelled

her “Judas Christ.” New York Post critic

Richard Watts admired “her skill with the stiletto.” And, Judy’s ultimate

favorite, the brilliant director Billy Wilder, who commented that inviting

Crist to review one of your films was “like asking the Boston Strangler for a

neck massage.” The Herald Tribune

years: “The best years of my life.” Began as a feature

writer on the “social significance page” for $27.50 a week in 1945, working

with Helen Reid and her boss, Dorothy Bromley Dunbar, Joe Hertzberg the much revered city editor. Became a general assignment reporter for

eleven years, second-string drama reviewer to the great Walter Kerr, and

finally, editor for the arts. “He is one of my few

Gods who never did diminish. I

worshipped him in every sense.” But the struggle to be

given “a voice,” her own critical voice, at the Herald Tribune took twenty

years of imploring and being told “It’s not the right time for my kind of

criticism.” The fateful turning

point was the protracted 114-day With the resolution of

the newspaper strike, things were in flux at The Trib. Herbert Kupferberg was

appointed editor for the arts. And on Six weeks later, she

became famous [infamous] with her scathing review of Spencer’s

Mountain, starring Henry Fonda and Maureen O’Hara, being shown at Radio

City Music Hall. “A film that for sheer

prurience and perverted morality disguised as piety makes the nudie shows at

the One month later the

storm of Cleopatra detonated, Crist in the center of the

maelstrom, the movie, an

extravaganza of riches, a grossly spectacular epic and the most expensive

film ever made in “At best a major

disappointment, at worst an extravagant exercise in tedium,” wrote Crist. Burton does not appear for the first hour

and twenty minutes, she points out, with another hour and 15 minutes before

their first tepid embrace, Miss Taylor’s “accents and acting style jarring

first with those of [Rex] Harrison and

later with those of Burton. She is an

entirely physical creature, no depth of emotion apparent in her kohl-laden

eyes, no modulation in her voice, which too often rises to fishwife levels.” “With the mystique of

Cleopatra missing, “…Even in their most

dramatic moment, when Cleopatra and Antony are slapping each other around in

her tomb, one’s most immediate image is of Miss Taylor and Mr. Burton having

it out in the Egyptian Wing of the Metropolitan Museum.” “The mountain of

notoriety has produced a mouse.” Crist achieved

“overnight” fame. She won the New

York Newspaper Women’s Club Award for her scorching review. 20th Century Fox cancelled its

ten ticket table and demanded its money back.

Joe Mankiewicz quietly sent a personal check to the Club to compensate

for the loss and over the years became lifelong friends with Judith. They

never spoke of Cleopatra. * *

* “Yes the sixties and the seventies were the

Golden Age, the great filmmakers who emerged and the movie stars in their

prime – and the newcomers. What a

burgeoning – the foreign films and the great filmmakers and the passion. “Woody Allen was reminiscing

in a recent letter to me about a major film festival in which we all wore

buttons that said ‘Fellini’ or ‘Antonioni.’

Woody was an Antonioni man. I

was an ardent Fellini person. “Yes, it was a kind of

golden age. I don’t mean to be in any

way derogatory but there was nothing to compare with some of the animated

movies of today – Ratatouille –sensational,

and Toy Story. From the standpoint of technology it’s

another Golden Age. And the actors of

today: “I go anywhere to see

Viggo Mortensen. I’m an avid admirer

of George Clooney. A belated admirer

of Leonardo DiCaprio. I also like Matt

Damon, Brad Pitt, Tommy Lee Jones, Russell Crowe, a very interesting actor. “I go to the movies once

a week with my kids, my son and his wife.

We geriatric ladies go on weekends to the early morning movie and talk

it all over at brunch.” Judith Crist has

maintained her intuitive affinity for the young – their cauldron of energy

and creativity and dreams of glory –

and drawn joy from it over half a century as an Adjunct Professor of

Journalism at the Columbia School of Journalism. Her students love her. Her favorite all-time class – the class of

1971 [of which David Pitt was a star.] The memorable Judith

Crist Film Weekends held in She gazes at a

photograph of her beloved husband of 45 years, William B. Crist, a public

relations consultant who passed away in 1993, who she only now has come to

realize, bore a strong resemblance to a young Paul Newman. Her son Steven Crist, is chairman of the

board and publisher of The Daily

Racing Form, brave like his mother. We conclude with an

excerpt from Judy’s caustic review of the 1967 Otto Preminger film, Hurry Sundown, which subsequntly won

the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award for Criticism. “For to say that Hurry Sundown is the worst film of the

still-young year is to belittle it. It

stands with the worst films of any number of years.” The prize was presented

at the banquet by Mayor John V. Lindsay, who was handed a telegram from the

great Preminger which he read aloud to the audience: “Congratulations on your night of triumph

from the man without whom all this would not be possible.” “The last word, as

usual, was his,” laughs Judy. |

|