|

Copyright (c) 2001 Ralph D. Gardner. All Rights Reserved, Terms and Conditions.

My Saturday Afternoons with Albert Einstein By Ralph D. Gardner |

||

|

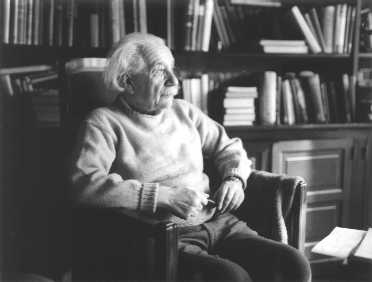

Courtesy of the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study Albert Einstein in his office at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, 1954. |

Ralph Gardner, 12, on a bench in Washington Square Park, the year 1935 . |

|

|

By Ralph D. Gardner

Being only eleven at the time, I had no idea that the year I was introduced to Albert Einstein -- 1934-- was among the most crucial in his life. During his visit to the United States, the Nazi government in Germany, where he was born in 1879, confiscated his property and revoked his citizenship. To Einstein, the most prominent scientist of this century and, at the time, an outspoken critic of Adolf Hitler, the German action was no surprise and, on receiving this news, Einstein accepted an offer to join the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he remained until his death in 1955. During my own career in journalism here and abroad I met heads-of-state, military leaders, literary giants and entertainers, but I do not recall a more companionable gentleman than Albert Einstein. Perhaps I was invited to meet him because I could speak German, a result of living with my maternal grandparents. My grandmother and her family arrived from what was then Bohemia when she was an infant. Though English was spoken to others, they conversed in German among themselves. Daily, at mid-morning, the family gathered for coffee at my grandmother’s brownstone, and though little was said to me, I absorbed the language. At the age of four I moved with my parents to an apartment building on Fifth Avenue where many interesting tenants dwelled over the years. Governor Al Smith lived there, as did the actress Ann Harding, Clare Boothe Luce, journalist A.J. Liebling, Stan Laurel, George Sanders, Peter Lorre and others. I met Albert Einstein through one of our neighbors, the petite, red-haired wife of distinguished Federal Judge Julian Mack. One Saturday morning, Mrs. Mack phoned my mother to say that Professor Einstein was coming to tea. Would I like to meet him? She somehow knew I spoke German, with which Einstein was most comfortable. During this period Dr. Einstein was a frequent visitor and I was present on four or five of these afternoons. Mrs. Mack and I would wait for him downstairs -- never for long because the professor arrived punctually. As he was regularly pictured in newspapers and movie newsreels, I recognized him, as did passersby. He was then fifty-five years old, considerably younger than I am today, and his dark hair and bushy mustache were turning gray. Einstein traveled from Princeton seated at the rear of a four-door luxury convertible touring car -- itself, attracting considerable attention -- that presumably was made available to him by Princeton friends as he, himself, was not wealthy. He and I talked in the Mack’s penthouse, and he seemed genuinely interested in what I said, usually in answer to his questions. Mrs. Mack busied herself in the preparation of tea, sandwiches and cakes, and the judge usually entered just before we were seated. Smoking a well-worn stubby pipe, Professor Einstein asked about my family and generously complimented me on my ability to speak German. "Do you like music?", he asked. "Yes," I replied, not really sure that I did. "Can you play some instrument?" "No sir." He told me he could play a violin. There was a chessboard set up between our chairs. "You play chess?" "No." I fear he’d think I couldn’t do anything. "Would you like to learn?" "Oh, yes." "Come. I’ll teach you." Until we were called to the table, the professor demonstrated the moves of each piece. "You practice," he said. "Next time we’ll play a game." Mrs. Mack told my mother that Einstein asked that I come back, and so I joined the great man on subsequent Saturdays. We played chess, with him suggesting how to avoid my wrong moves and how to maneuver pieces to better advantage. I don’t remember ever winning, though we probably never completed a game before tea was served. Tea finished, Einstein and I shook hands as he and Judge Mack entered the judge’s study for their own discussions, which doubtless were the purpose of his visits, and I departed. I later learned that they both actively helped victims of Nazism -- many were distinguished scientists -- to escape and to find jobs in American universities, which could have been a reason for their meetings. Albert Einstein became a United States citizen in 1940 and expressed his love for America in letters and books which often were written in German. In "Ideas and Opinions," a collection of his writings, he observed: "What strikes the visitor with amazement…is the joyous, positive attitude toward life. The smile on the faces of people in photographs is symbolical of one of the greatest assets of the American. He is friendly, self-confident, optimistic -- and without envy." I had no further contact with Albert Einstein until 1951 when, given a photo portrait of him, I mailed it to him and asked that he autograph it for me. Doubting that he recalled our tea and chess at the Macks, I noted that his patience and kindness to an eleven-year-old boy remained a heartwarming recollection. He did remember, and inscribed the photograph for me. And that portrait remains a most treasured possession to this day.

_____________________________ Ralph D. Gardner is a former New York Times editor and host of a talk show on books.

|

||