|

Eros Unbound |

|

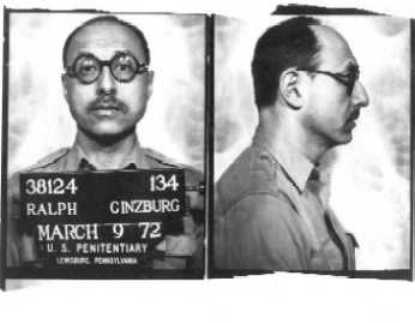

By Ralph Ginzburg

Publisher Ralph Ginzburg's

penitentiary mug shots, |

|

By Ralph Ginzburg What's it like to be a newsman charged

with a crime and suddenly be confronted by a hostile press? It happened to me

in 1962 and the aftermath has continued to warp my career to this day. I had studied journalism at CCNY, was

editor-in-chief of its downtown campus newspaper, and on graduation in 1949

began my professional career as a copyboy and cub reporter at the New York

Daily Compass, successor to the pioneering PM. Two years later I was drafted

into the Army during the Korean war and assigned to Upon discharge from the Army I shifted

into broadcasting and magazines (NBC, Reader's Digest, Collier's, Writers and other intellectuals

throughout the world celebrated it. Even the U.S. State Department bought

copies to exhibit at USIA libraries overseas as exemplars of American

periodical publishing. But bluenoses here at home railed against

the publication and one, the New York smut-hunting Catholic priest Morton

Hill, persuaded U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy to have me indicted, as

Father Hill later boasted, for distributing "obscene" literature

through the mails, a federal crime. The indictment sought punishment of

$280,000 in fines and 280 years in prison. But newspapers ignored my every attempt

to defend myself against |

|

these moronic allegations. I announced

press conferences at various sites around town: at the Benjamin Franklin

statue on Newspaper Row, at my magazine's offices, on the steps of the

General Post Office. All were listed in the AP and UPI

daybooks but nobody showed up -- with one exception: Gay Talese,

then a star reporter for The New York Times, appeared at my Post Office press

conference where I presented an impassioned rebuttal of my attackers' charges

and answered his few questions. I distinctly remember that he jotted down not

a single word of my remarks. The Times ran no story the next day and Talese went onto become vice president and a director of

P.E.N., the international organization dedicated to combating censorship of

authors and publishers. After a brief trial in June, 1963, I was

convicted in U.S. District Court, The High Court's Salemesque

judgment, authored by the oft-lionized-as-a-liberal William J. Brennan, also

upheld my conviction, along with its bloodletting fines and prison sentence

of five years. Three days later, on March 24th, The New

York Times intoned: "The Supreme Court has struck the proper balance in

a field where there are extremely difficult issues of law and public

policy...Mr. Justice Brennan and his majority colleagues have shown wisdom

and moral courage in the subtle and arduous task of upholding the law against

obscenity while still protecting liberty of expression... "Ginzburg

was clearly publishing pornography...The Court inescapably concluded that Ginzburg had no scholarly, literary or scientific

interests; he was strictly an entrepreneur in a disreputable business who

took his chances on the borderline of the law and lost... "The pornographic racketeers have

cause to worry and their defeat is society's gain." I read the Times and Supreme Court

opinions in horror. At the Court, the vote was five to four, with five

disparate opinions among the nine Justices. It was a legalistic free-for-all.

Finally, a majority of five panicky Justices prevailed, convinced that I was

a menace to society who had to be put behind bars. Suddenly, when it was too late to aid my

defense, newspapers became highly vocal. Stories, editorials and

letters-to-the-editor appeared everywhere, most concurring in the Supreme

Court's ruling (and written, I've always suspected, largely by individuals

who had never seen EROS). From clipping services, the stories poured into my

offices by the thousands. But I was not without my champions. Several leading lawyers, writers, artists, and even a number of non-Catholic clergymen, were |

|

outraged by the Supreme Court's ruling.

Novelist Sloan Wilson, a heroic stranger who appeared at my office from out

of nowhere one day, organized an emergency defense committee which raised funds

for full-page newspaper protest ads. These eventually succeeded in having my

prison sentence reduced from five years to three, and in gaining my parole

after I had been locked up for eight months. Again, shortage of space prevents me

from quoting the dozens of renowned figures who were aghast over my

conviction. They included Melvin Belli, James

Jones, the ACLU's Mel Wulf, Nat Hentoff,

Ashley Montagu, Yale Law Professors Alexander

Bickel and Tom Emerson, Clay Felker, Louis Untermeyer, I.F. Stone, Barney Rossett,

Ken McCormick and others of stature. Their fury is quoted in full in my

prison memoir, "Castrated: My Eight Months in Prison" (Avant-Garde Books, 1973, and published almost en toto in, ironically, the Sunday magazine of The New York

Times -- after I had been tried and imprisoned). But I would like to quote just one of my

defenders, the playwright Arthur Miller: "After all the legal, moral and

psychological arguments are done, the fact remains that a man is going to

prison for publishing and advertising stuff a few years ago that today would

hardly raise an eyebrow in your dentist's office. This is the folly, the

menace of all censorship -- it lays down rules for all time which are

ludicrous a short time later. "If it is right that Ralph Ginzburg go to jail, then in all justice the same court

that sentenced him should proceed at once to close down ninety percent of the

movies now playing and the newspapers that carry their advertising. Compared

to the usual run of entertainment in this country, Ginzburg's

publications and his ads are on a par with the National Geographic." The lesson of this lamentable saga is

clear: American newspapers can be counted on to defend freedom of the press,

but only one kind: their own. |