|

Copyright ã 2003 Herbert Hadad.

All Rights Reserved [Terms and Conditions] Looking for Mr. Goodbar By Herbert Hadad |

|

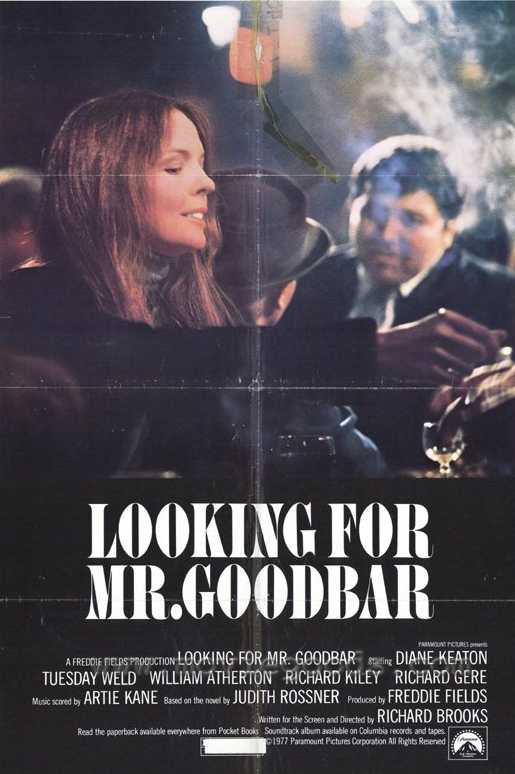

Paramount A complex and chilling film that inspired fear in the hearts of

young single women on the prowl.

|

|

By Herbert Hadad Mr. Goodbar, the symbol of which

terrified a generation of New York women in the latter part of the last

century, was a real person with a different name. I

found the real Mr. Goodbar within 10 days of his crime. I called Mr. Goodbar

but Mr. Goodbar never returned my call. Let

me tell you the tale. I was a newcomer to New York journalism, working for

the New York Post, and the murder became my first important story. With a

little digging and a lot of luck, I found the alleged killer -- his name was

John Wain Wilson -- and the District Attorney's office asked that I put away

my notes and keep the discovery a secret. "We

think you've got the right guy but if you print anything you'll spook him and

kill the case," they said. My

editors went along. After waiting for the D.A. to cinch the case and hand

back my exclusive -- the story that would help make my reputation -- I got

impatient and called Wilson myself. He

lived in an apartment in Chelsea. "He's not here just now," said

his older roommate. "He's visiting his family in the Midwest and should

be back in a week or so." The

roommate gave me the right dope, but it was incomplete. Wilson came back in a

week or so from the Midwest, but he was manacled to about five cops, who

tossed him in a downtown hostelry called The Tombs. The

Goodbar story began one morning as I sat on the Post's rewrite bank. (A

rewriteman, as most of you know, is the one who takes the research, as well

as the exaggerated and sometimes hysterical observations of the reporter at

the scene, and crafts them into a readable yarn.) "Kinky murder on the West Side,"

said the City Editor, Larry Nathanson. "Take it on line 6." What

I got was a description of a young female victim, beaten on the head with a

small piece of statuary as she lay in her own bed. The headmaster of a school

for the handicapped had called when she'd failed to show up at her teaching

job for a few days. Someone was let into her apartment and made the

discovery. The only other bit of information was that she was last seen alive

leaving a bar near her building with a young man. Being new to the paper, I was especially

eager to make a good impression. Within minutes I was reeling off paragraph

after paragraph of crisp prose on the size and quality of the apartment

building, the ambience and habitation of the bar where Roseann Quinn -- the victim's

real name -- had apparently met her killer, the rhythm and color of the

street late at night. "This is damn good stuff,"

exclaimed the editor. "Where're you getting it?" I tapped my moist forehead. "I live

next door to the All-State Café and across the street from Quinn's place,

with the Gristede's on the first floor," I confessed. An intimacy developed between the

principals of the crime and the chronicler. She was already Roseann, my

victim, and I was going to do all I could to make the story bigger and better

-- and maybe even crack the case. For the next several days I used my spare

time visiting the grocers, cleaners, newspaper stand and other spots where

Roseann likely shopped. They were the same merchants I used and were inclined

to be helpful. A few knew her -- the dry cleaner by name from writing up

tickets for clothing left -- as a pretty, quiet young woman who walked with a

slight limp. I

reached the headmaster. She was kind and patient with the children, he said,

and came from a good and pious family in New Jersey. They were of no help. After a while, the story began to cool.

Until I learned that police had visited a midtown office and asked lots of

questions about a young male employee. No one had said anything outright, but

the cops left the impression they were looking for Roseann's murderer. I had

a friend at the company. "I'll lose my job if they trace this

back to me," he said. I blithely promised him anonymity. He then told me

about Wilson, the tall, slim, handsome man who had been taken on as a

mailroom clerk and who had become a favorite of the young women. "He

loves to take them downstairs for an ice cream soda, and they love

going," my informant said. "Beyond that, I don't know much about

him or his habits." But he gave me Wilson's name and remembered

that Wilson stopped coming to work - vanished, in fact - about two days after

Roseann Quinn's body was found. If he was right and Wilson was indeed the

killer, it meant that Wilson came to work the morning after the slaying and

continued to make his soda-fountain dates, but that something made him run a

few days later. The

contrast of the killer and the wholesome youngster sipping malteds was

intriguing, and I think we could have run the story without the suspect's

name. But someone allegedly smarter than I was offered the information to the

D.A. instead, and there went that day's story and most of the ones after

that. As

most of us know, the case became really famous following publication of the

book, "Looking for Mr. Goodbar," and the movie adaptation. They

dramatized the danger and shallowness of New York night life as young women

tried to meet eligible young men. For the record, it was later disclosed that

Roseann and Wilson met in the All-State Café on West 72nd Street between

Broadway and West End Avenue and then proceeded to her apartment across the

street. When Wilson declined or became incapable of romantic endeavor,

Roseann either kidded or taunted him. He became enraged and beat her to

death. So Wilson was returned from the Midwest, and

the court reporters anticipated a real juicy trial. But then came the call I got from the Post's

legendary court reporter, the man with his own table at Forlini's restaurant

on Baxter Street behind the courthouse, Mike Pearl. "You hear from Wilson yet?" he

asked. "No." "Well, you won't. Scratch Wilson. He

just hung himself in his cell." |