|

Copyright „ 2003 Herbert Hadad.

All Rights Reserved [Terms and Conditions]

Learning the Ropes By Herbert Hadad

|

|

|

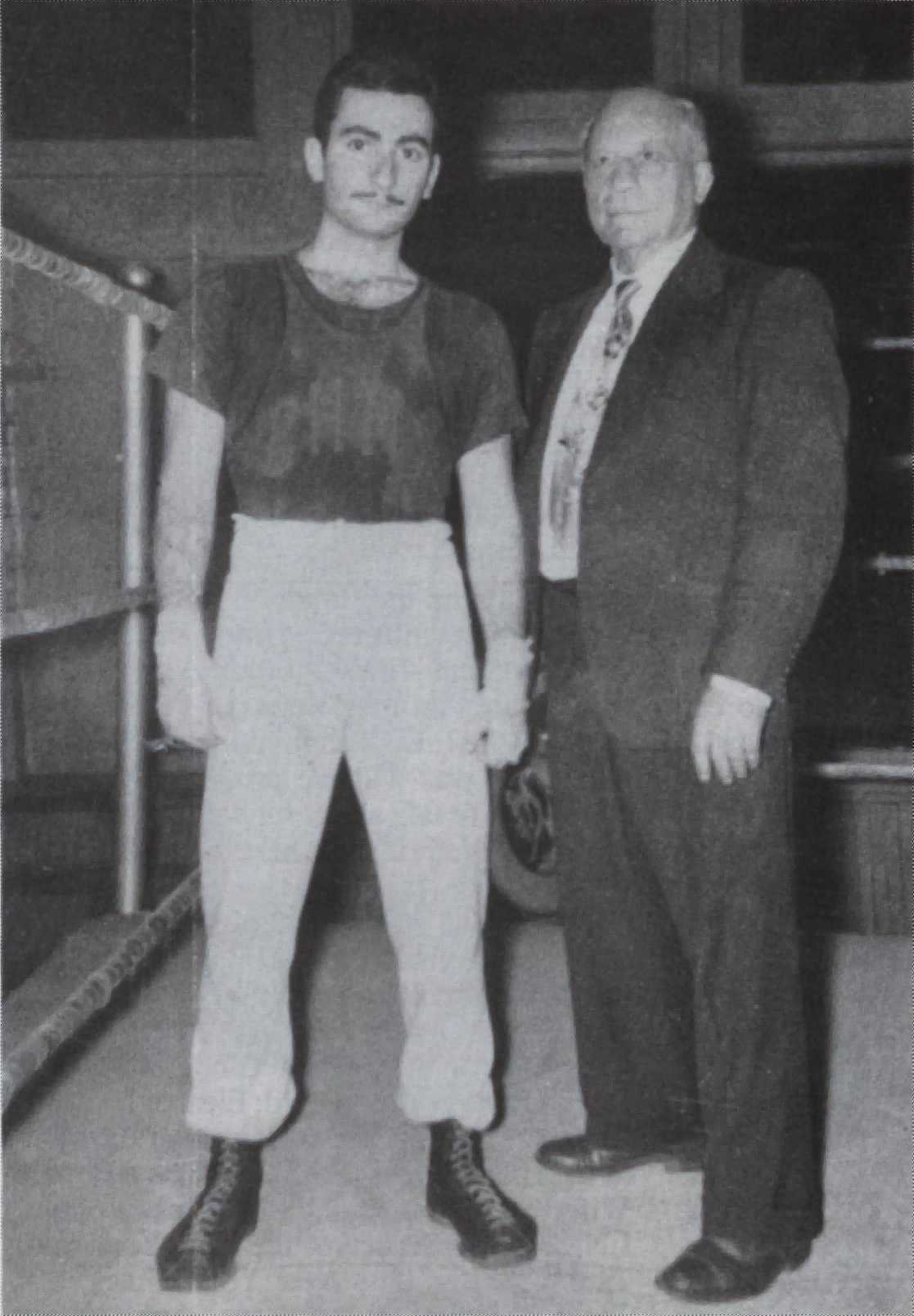

Herb Hadad and the legendary Al Delmont, New Garden Gym, Boston, Massachusetts |

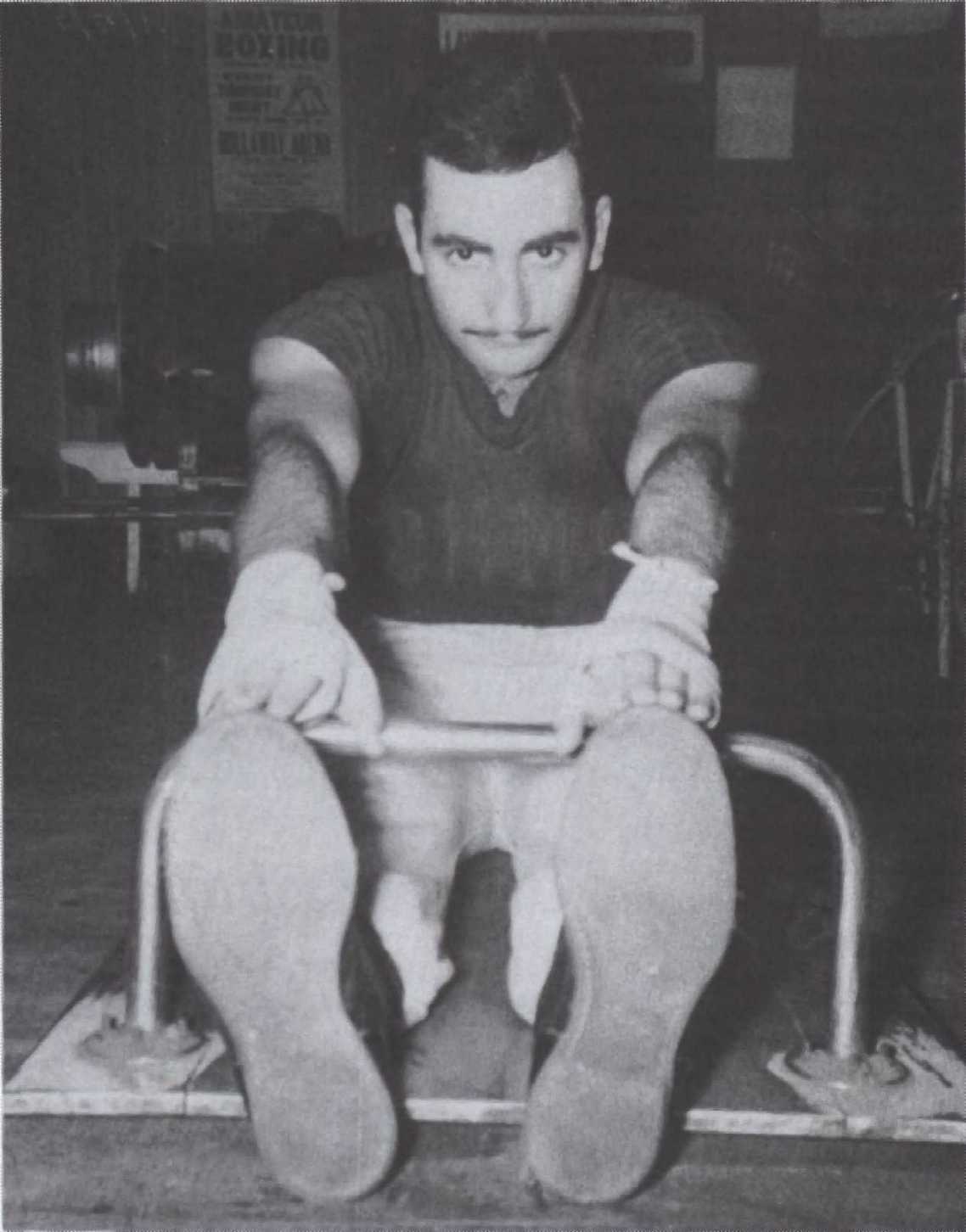

Herbert

Hadad in his glory days as a featherweight fighter. |

|

By Herbert Hadad Escaping a drab autumn afternoon, my

date and I ducked into a Greenwich Village tavern, and perched on stools like

slightly damaged icons were three of the greatest prizefighters in American

history. I left her side and floated by Rocky Graziano and Jake LaMotta and

reached to shake the glorious right hand of Willie Pep. "I saw you fight

in the old Mechanics Building on Huntington Avenue in Boston. You were

sensational. You were my favorite fighter in the whole world," I said.

Pep, wiry and bony-faced and surprisingly tall for a man who fought at 126

pounds, introduced us to his companions with their famous flat mugs and

hoarse voices, but then we coaxed him away and he allowed us to buy him a

drink. He seemed pleased and embarrassed by the attention. Twice the

featherweight champ, Pep had been the subject of a nasty article in a

national magazine. It had made fun of his life in retirement, his business

dealings and marital troubles, and suggested he had left several of his

marbles back in the ring. "It was unfair, Willie," I told him.

"It was bad journalism." You may not know that many fighters are

sentimental saps outside the ring, and Pep began to worry that I was upset.

"Itís okay, kid," he said. "Itís okay. I call roll with the

punches." I reminisced about his trademark move in

the ring. No matter how often you saw it, the maneuver seemed more magical

than real, something invented by a master cartoonist. The opponent would wind

up and throw a big right, but by the time it arrived Pep was gone. Dumbfounded,

the fighter would turn and discover Pep waiting behind him, ready to bop him

in the chops. I asked the ridiculous. "How did

you do that, Willie?" He grinned and kneaded my left shoulder

with his famous right hand. "I ought to get back to Rocky and

Jake," he said. I was beside myself with excitement. Outside on MacDougal Street, my date

Evelyn, who would become my wife, allowed me to rewind the encounter like a

fight film and run it over again, pausing at favorite moments. "Remember

how I told him he was the best and he got shy and hung his head like a little

boy?" I said. "I think he liked you," she replied. Willie Pep would have liked me a lot

less if he had known one important fact I had withheld. Not so many years

before our meeting, I had wanted to be the featherweight boxing champion of

the world. And I would have tried to destroy him or anyone else who stood in

my way. I come from a rather religious home.

"Thou shall not smite, although an occasional eye for an eye may be

justified" was the message I remember. My mother and father, sister and

brother loved me and I them. We had plenty to eat. I was no more or less

popular than the other kids in our Roxbury neighborhood. I was in college,

tussling with the rudiments of economics at Northeastern. I had a co-op job

as a copy boy at the Boston Globe, which I had sized up as fun without

a future. People said I had a sense of humor. Yet some combustible

combination of ambition and rage and yearning for recognition and wealth not

promised by my station propelled me into the dangerous business of boxing. It

sent me to war. One day I packed a gym bag and headed for a place where I

heard real boxers trained. I climbed the stairs to the second floor of a

small, shabby building on Friend Street, half a block from Boston Garden,

pulled open the door, and entered a brand new world. Young men, black and white,

shadow-boxed, lit into heavy bags, slapped the speed bag with rat-tat-tat

precision, took hurled medicine balls in the stomach, grunted through

sit-ups, met in musty corners of the large room receiving the cunning and

wisdom of their trainers, whose fashions consisted of cardigan sweaters and

towel-draped shoulders. An adjoining room contained lockers and showers. But

the centerpiece of the big room was an elevated canvas ring where fighters

sparred above the watchful eyes of handlers and hangers-on. The rhythm of all

activity was dictated by an automatic bell, which rang in intervals of three

minutes (for work) and one minute (for rest). A strange man materialized. He wore a

gray felt hat and open-necked, white shirt and had a fat, moist lower lip by

which he spit slurred words. He also carried a deadened right arm that he

tapped with his left hand and swung up when needed to support his clipboard.

"What can I do for you?" he said, not unkindly, and told me the

monthly fees for training at the famous New Garden Gym. I remember my reply exactly. I was

determined not to be scared, so I ended up sounding like a wise punk. "I

think Iíll try one of your better $5-a-month accommodations," I said. For several weeks I trained in

isolation, talking to no one except Angelo, the man who had rented me a

locker. Every afternoon I spied fighters and tried to mimic their routines.

Nights I co-oped at the Globe. Mornings I did roadwork, either

in Franklin Park or around Jamaica Pond, squeezing smooth, round rocks as I

ran to strengthen my hands and wrists. I read Ring magazine. I

learned that a great fighter of a bygone era had perfected his moves by

emulating the speed and stealth of cats. I began to study the neighborhood

cats. One day as I punished the dangling heavy

bag, whacking it until it flew toward the ceiling at the end of its chain, a

man in a brown suit and hat, an unlit cigar in his right hand, approached me.

"Anybody handling you?" he asked. He was sixty, maybe seventy years

old. He was small and handsome, like Picasso with a flat nose. I told him no.

"Want somebody?" I was very excited, although I had no idea who he

was. "You have to promise to listen to me and not all the malarkey

thatpasses for boxing advice in this gym. Iíll be your trainer and your

manager. When youíre ready, Iíll take a cut of your purse. I wonít be greedy.

I wonít let you get hurt." Then the legendary Al Delmont,

considered by many the premier bantam- weight boxer of the earlier decades of

the twentieth century, conducted the first of countless lessons that prepared

me for life in the ring and, as it turned out, way beyond the ring. He put down his cigar, got into a boxing

stance, and gave the bag a right-hand shot. A tremor went through it,

but it hardly moved. "You were pushing with your punches. Thatís why the

bag swung all over the place. A good punch starts down in your feet, comes up

your legs and across your waist, up through the shoulders, and down your arm.

Your fist shouldnít move more than six inches." What followed were months of induction

into the arcane knowledge of how to rob your opponent of his dreams and put

him out of his misery as quickly as possible. Al, as he allowed me to call

him, worked me into exhaustion, blocking, rolling underpunches, jabbing until

my left arm was almost numb, faking with my shoulders, learning to keep the

right cocked for that perfect split second, saving the uppercut for the

unwary fool. He taught grace but not mercy. "He

drops his right, slam him in the ear with your left hook. He pulls up his

head and prances like a peacock, slide in and let him have it in the Adam's

apple." Although I became weary in the gym, he

believed he was preaching temperance. "Everything must be done in moderation,"

Al was fond of saying. "Not too much training or running or women."

I was so pleased that he thought I might have a reckless sex life that I

never corrected him. A short time later, back in school to

spar with Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes, I took part in a boxing class

at Cabot Cage. The instructor matched me up with

another student, and we began the round. I waited for an opening and tried

out the six-inch right hand Al Delmont had revealed to me. It exploded

against the guyís head. He went down and out. Someone rushed for water. In my

hubris, I was too awestruck to be scared. They brought him around and back to

his feet. I apologized and he told me not to worry. Al booked my first fight. I called in

sick at the Globe, not intending to cheat them but concerned about the

ribbing I would take if the scholar-warrior returned vanquished to the city

room. The stadium in East Boston was big and bright and noisy. The audience,

I later learned, included a group of pals from college, my dad and younger

brother, and the neighborhood gang, a few of whom were jealous of my new

notoriety and had come to witness my union with the canvas. Nearsighted, I

could not make out faces in the crowd and, in fact, could not see my opponent

with clarity until we were almost on top of each other. During introductions, I got more

applause than Hector Valdez, but when the bell rang for round one, all sound

ceased and I stepped into an interior realm inhabited only by me and my

opponent. He tossed several flurries of punches and drew blood from my left

ear, but he didnít seem to have the skill to intercept my jab. Between

rounds, Al Delmont said I would have to fight harder or I could lose. I raced

out and jabbed and jabbed and waited for the moment and delivered the right cross.

Valdezís knees buckled and he fell against me and clinched. "Fall down,

for crissakes. Iím gonna kill you," I whispered. "I canít, I canít,

they wonít pay me," he answered. The bow-tied referee glided in.

"No talking," he said and pried us apart. The announcer collected the votes, and I

was the winner by a unanimous decision. The referee held up my arm. People

applauded and cheered. I crossed the ring in the ritual that dictates you

praise the fighter for his courage and the manager for his skills, and

returned to my corner. "Thank you, Al," I said. He smiled.

"This is your night. Keep all the earnings." In the locker room

under the stadium, a man pulled some cash out of a white envelope and gave me

$25. I was a professional prizefighter. |

|

ALIGN="CENTER"><