|

By Joseph Wershba

"Nothing enhances a man's

reputation as much as his funeral." William Randolph Hearst had to wait

a half century for a revised obituary. Considering the alternative, it was a

worthwhile wait. In films, television, books and book reviews, Hearst is

enjoying a posthumous resurrection. He has broken out of his Orson Welles

transmogrification as yellow journalism's ineffable monster and now

luxuriates as one of publishing's great--and perhaps greatly

misunderstood--giants. It should not take long before the name of William

Randolph Hearst settles comfortably beside the ever-revered journalistic

names of John Peter Zenger and William Lloyd Garrison. Can beatification be

far behind?

Two things to remember about Hearst:

First, "Citizen Kane" was a movie--one of Hollywood's greatest--but, withal, a movie. It was not a

biography, not a documentary; it frequently bore little likeness to the real

Hearst, especially to Hearst's ever-loyal mistress, Marion Davies, who could

have been the finest screen comedienne of her time had Hearst let her be

herself. Second, Hearst was always passionate about his crusades--even though

the latest crusade might contradict the previous one. But he was never all

one thing or the other, never a true socialist, never a fascist although

different critics in different periods of his long career made their case

against him in his own words. Hearst was Hearst. His principal interests were

circulation--political power--and himself. Never mind his critics who called

him a pathological egotist who listed Julius Caesar and Napoleon among his

role models; Hearst insisted his true model was always Thomas Jefferson. More

than anything, however, Hearst was a true believer--in himself. Once he

established a truth in his own mind, his fleet of newspapers, magazines,

newsreels and all the engines of propaganda at his command were wheeled into

artillery fire against the non-believers.

This was the man who almost made it to

Mayor of New York City, almost made it to Governor of New York State, almost

made it to President of the United States. To such a man, attention must be paid.

But what was curious about the "new

look" of Hearst--the editor-publisher who was for so long the scourge of

communism in schools, trade unions, motion pictures, churches and government

itself--is that there was little in-depth examination of one of his greatest

and longest-lasting crusades:

The Bolshevik Revolution.

Hearst was for it. Not against

it.

From the winter of 1917-18 until the

winter of 1934 Hearst was one of the greatest American friends Communist

Russia ever found. Hearst welcomed the Bolshevik Revolution, characterized

its leaders as true democrats, sympathized with its aspirations, urged its

diplomatic recognition and continued to be a well-wisher of the Soviet Union--until Adolf Hitler burst upon the world.

Context: Hearst had fought passionately

against U.S. involvement in the Great War that began in

August of 1914. Much of his readership agreed with the populist line that the

war was a struggle amongst imperialist nations for conquest and pelf, and

meant no good for the common man who would have to fight and die for the

wealthy. For the two and a half years before Woodrow Wilson took America into the war--in April of 1917--Hearst had been

trenchantly anti-British, so much so that he gave the impression of sympathy

for the Kaiser's Germany. But once America was in the war, Heart's editorial heart bled

pure patriotic gore. No one hated the Huns more than this former sympathizer.

Hearst's critics, however, smote him ceaselessly as disloyal, seditious,

treasonous, un-American and even a propitiator of pro-German espionage. He

was a well-hated man.

Having failed to achieve direct

political power as Mayor, Governor or President, Hearst sought mastery

through influence. In November, 1917, he marshaled his New York newspapers behind John F. Hylan for mayor. The

opposition decreed that a vote for Hylan was a vote for Hearst and a vote for

Germany. Hearst's editorial response came in the slogan

of that old (and misrepresented) British standby: "Patriotism is the

Last Refuge of a Scoundrel." The European War, already drenched in the

blood of millions, thirsted for more. French and British reinforcements were

rushed to the Italian front; the Italians, according to Hearst's New York American, were conducting a

"masterly retreat"--something the Italian generals had gained a

reputation for perfecting. And worse trouble for both sides was brewing

eastward.

A two-paragraph squib, stuck away on

page three in the November 3rd issue of The American," was headlined: "Bolsheviki

Crushed in Russian Elections." 643 towns had given the Bolsheviks

only seven percent of the vote. (Though the word "bolshevik" meant

majority, in November 19l7 they were actually a minority.) There were

disquieting stories out of Petrograd quoting Prime Minister Kerensky that Russia was worn out and needed help desperately.

Kerensky subsequently corrected any wrong impression his words had made. He

promised firmly that Russia had no intention of quitting the war.

On November 7, 1917, Hearst's two New York newspapers--the Journal and the American--joyously

reported the impressive victory of Hearst's protege, John F. Hylan. For Hearst,

it was a victory over the unholy alliance of Tammany Hall, big business, Wall

Street, monopoly and plutocracy.

Also November 7, 1917: the Italian armies had turned a masterly

retreat into a full retreat from the Tagliamento Line. The British--actually,

the Canadians on the Western Front--were reported to have taken

Passchendaele, one of the war's greatest graveyards.

And on November 7, the Bolsheviki seized

power. Hearst's front page streamer:

"NEW REVOLT IN PETROGRAD."

The Bolsheviks, self-styled followers of

Marx and Lenin, had the support of considerable numbers of Russian troops who

no longer would permit themselves to be used as cannon fodder for ignorant

Russian generals to squander without end. Lenin's slogan was simple and

powerful: Bread, Land, Peace.

Bread for the starving masses; land, to

be seized from landowners and given to the destitute peasantry; peace, with

the Kaiser's Germany, to get Russia out of the war. The power to create a new social

order would be vested in workers' and peasants' councils (Soviets) with

delegates from the soldiers.

In Lenin's profuse writings, speeches

and organizing efforts, he made it clear that capitalist power (the

bourgeoisie) must eventually be swept away, to be supplanted by a workers'

dictatorship (the proletariat). This dictatorship of the proletariat would

revolutionize the entire social order, it would eliminate classes and thus

eliminate class warfare and eventually lead to the "withering away"

of state power.

However, until the "withering"

happened, the Bolsheviks would provide the leadership of state power. Any

opposition by the bourgeois enemy would be crushed without pity. The

Communist Party would be the "vanguard"--the controlling force.

Hearst readers were left in little doubt

as to the all-encompassing nature of the Bolshevik Revolution. Despite all

the chaos of the spreading revolution, chaos compounded by

counter-revolution, civil war and foreign intervention, the confusion in

newspaper reports was understandable. But even at this remove in time, the

Hearst papers' reporting on the first days of the Bolshevik revolution stands

up as accurate.

But where did The Chief--William Randolph Hearst--stand?

Hearst still wanted an honorable end to

the Great War. He moved carefully. On December 28, 1917, the New York American--in an unsigned

editorial--commented that the Bolshevik peace proposals were certain to be

accepted because "The German PEOPLE and the German ARMIES are very

largely in accord with the Russian proposal of peace without annexations or

indemnities or commercial boycott." This was followed on January 7,

1918 in another American

editorial: "The peace terms of Russia are basically the same as those of the United States, and the peace terms of the allies should be

made to conform with the peace terms of those essentially democratic

nations."

January

28, 1918, another

unsigned trial balloon in the American. Whether it was Hearst's balloon or

the individual editor's, it was nevertheless a trial because it was not to be

repeated in any form for another thirty days. The headline said: "In

a True Sense the Great War for Human Freedom is Won." It read:

"How stands the word's great war

today? Which is winning? Imperialism or Democracy?

"The world is democratized at this

very minute.

"All the governments in the world

are powerless now and henceforth to hinder that fact."

[Redder than the Rose? Wait. There's

more.]

"The common people of the

earth--Bolsheviki, proletariats, internationalists--call them what you

will--are marching steadily to victory over the dominions and powers, over

the autocracies, the money-lords and the constitutions, laws, institutions

and traditions which have for thousands of years saddled and bridled the Many

for the Few to ride and spur.

"The old order is not changing. It

HAS changed. It awaits only exterior peace to vanish away completely in swift

revolutionary uprisings in every country in Europe.

"Amid the thunder of the cannon and

the roll of the war drums, the race of Man has overleaped the breadth of

centuries in three hugely eventful years, and the vanguards of progress and

uplift stand at this very hour where, but for the impetus of the world's

agony, they might not have stood for a hundred years or more to come...

"We are well aware that this is not

the view of the chancelleries and the ministries and that it is not the

common view.

"But we think it is the just view,

the really statesmanlike view, the foreseeing view--and the view that will be

finally approved and ratified by the progress of events and the final verdict

of time."

But was it the view of William Randolph

Hearst, the single most influential publisher in the United States? Editorials in the Hearst press--signed or

unsigned as this one was--invariably reflected the view of the owner. In this

case the owner begged to differ with his editor: the first editorial did not

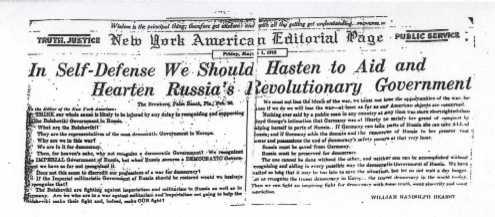

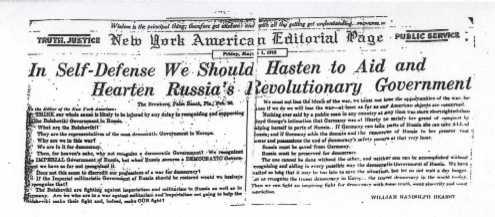

go far enough. Thus, one month later, March 1, 1918, in a half-page editorial, eight columns wide,

William Randolph Hearst told his editors and the world where he stood on the

Bolshevik Revolution. The headline read: "In Self-Defense We Should

Hasten to Aid and Hearten Russia's Revolutionary Government" The body of the

editorial, in the form of a signed letter:

"The Breakers, Palm Beach, Fla., Feb 26

"To the Editor of the New York American

"I think our whole cause is likely

to be injured by any delay in recognizing and supporting the Bolshevik

Government in Russia.

"What are the Bolsheviki?

"They are the representatives of

the most democratic Government in Europe.

"Why are we in this war?

"We are in it for democracy.

"Then for heaven's sake, why not

recognize a democratic Government?

"We recognized THE IMPERIAL Government of Russia, but when Russia secures a DEMOCRATIC Government we have so far

not recognized it.

"Does this not seem to discredit

our professions of a war for democracy?

"If the imperial militaristic

Government of Russia should be restored would we hesitate to recognize that?

"The Bolsheviki are fighting

against imperialism and militarism in Russia as well as in Germany. Are we who are in a war against militarism and

imperialism not going to help the Bolsheviki make their fight and, indeed,

make OUR fight?

"We must not lose the ideals of the

war, we must not lose the opportunities of the war, because if we do we will

lose the war--at least as far as our American objects [sic] are concerned.

"Nothing ever said by a public man

in any country at any time was more short-sighted than Lloyd George's

intimation that Germany was at liberty to satisfy her greed of conquest

by helping herself to parts of Russia. If Germany can take part of Russia she can take ALL of Russia; and if Germany adds the domain and resources of Russia to her present vast power and possessions the

end of democracy's safety occurs at that very hour.

"Russia must be saved from Germany.

"Russia must be preserved for democracy.

"The one cannot be done without

recognizing the other, and neither one can be accomplished without

recognizing and aiding in every possible way the democratic Government of

Russia. We have waited so long that it may be too late to save the situation,

but let us not wait a day longer. Let us recognize the truest democracy in

Europe, the truest democracy in the world today.

[emphasis added] Then we can

fight an inspiring fight for democracy with some truth, some sincerity and

some conviction.

--William

Randolph Hearst"

That was the Hearst policy as early as

March, l918, and despite the vicissitudes of revolution, counter-revolution

and immeasurable slaughter, that cornerstone of Hearst policy--to give

Communist Russia diplomatic recognition and save her for democracy--would

continue for another sixteen years. Two weeks after the signed Hearst

editorial (March 11) an unsigned editorial appeared in the American under

the headline: "It is an Outrage to Call the Bolsheviki Traitors to Russia." The editorial inveighed against the

spirit of mob violence being pursued by anti-Socialist orators; it pleaded

for a hard look at the history of Czarist barbarism, tyranny and cultural

darkness in pre-Bolshevik Russia, it upbraided the deposed Kerensky for

prolonging Russia's agony in the war, and defended Lenin,

"whose patriotism no intellectual man in Europe ever challenged." The editorial added:

"The Bolsheviks were compelled to

sign an unjust, inconclusive peace for Russia alone because of apathy abroad and treachery at

home. The United States of America did not recognize the Bolsheviki as the

Government of Russia--although they certainly are the actual and

representative

Government of Russia--because the aristocracies of Europe did not want the proletariat of Russia established in power.

"The modern revolution has not yet

arrived except in Russia, but it will come. Every day of war is bringing

it nearer and surer. 'We will renew the fight,' said Lenine [sic]

pathetically and patriotically, 'when we receive the support of the

proletariat of the world.' But the proletariat of the world are not in power,

except in Russia, and the autocracies and the privileged classes of the world

in this war for 'democracy' would rather see Russia defeated and dismembered,

destroyed and lost to democracy than see the proletariat of Russia survive

and the new revolution succeed."

Thus, the Bolsheviks had found a

constant friend in William Randolph Hearst--leader of the Premature

Recognitionists.

His newspapers regularly inveighed

against the "yellow peril" of Japan; they carried his signed editorial against Russian

Cossacks who were conspiring with Japan to invade Vladivostok. There was mounting talk that the United States would intervene with its allies in unofficial

war against the Bolsheviks; indeed, American soldiers on the Siberian front

moved against the USSR, ostensibly to rescue some allied troops who had

been surrounded. Hearst papers came to the vigorous defense of Lenin, Trotsky

et al. The American editorial of June 3,1918 was headlined: "It would be Wise to Cease

Sneering at the Bolsheviki." The Reds, in effect, had quit the war. But

the Hearst editorial was a lengthy ode of praise and sympathy:

"It is the part of statesmanship,

wisdom and justice for the American people to inform themselves of the real

character of the Bolsheviki and to understand that the Bolsheviki have

committed no act of treason or disloyalty to their allies; that they have

done nothing that we in their circumstances would not have done; that they

are today working out the problems of democracy as they can never be worked

out by war in Russia.

"Let the American people understand

the Russian people, let the American people sympathize with their difficult

problems and their democratic aspirations and be determined to encourage and help

them in every possible way. Let them discountenance the denunciation of the

Bolsheviki by men who pretend THEY are for this war for the sake of

democracy, but who hate the Bolsheviki because the Bolsheviki are real

democrats.

"Let the Russian masses be once

convinced that the American people and the American government are really

with them, and all doubt of victory in this war will be over. The whole force

of Russia will be on the side of America."

* * *

February

1, 1924: the British

Labor Government of Ramsay MacDonald announces that Great Britain will officially recognize the Government of

Soviet Russia. Mussolini's Italian fascist government confers diplomatic

recognition on Bolshevik Russia that same week, followed by Norway and Czechoslovakia. France delays recognition until October, and Japan recognizes Russia three months later, January 1925. The defeated

Germans had already cemented diplomatic bonds of friendship with the

Bolsheviks in 1922.

But despite the powerful campaign of the

Hearst newspapers across the country, a campaign for recognition that had

begun in March 1918, the United States would remain adamantly opposed for ten more

years.

Why had England and the others recognized the Soviet Union? For Hearst, the answer was simple. Diplomatic recognition

had nothing to do with friendship. It had everything to do with the

possibilities of trade. From an editorial in the New York American, February 8,1924, titled: "Why So Slow to Recognize

Russia":

"Despite the inspired opposition of

our State Department, the United States cannot much longer delay the official

recognition of Russia…It is a matter for regret that our own just appraisal

of the situation has not, long before this, determined renewal of

relationship between the United States and Russia. As it is, the example of Great Britain is certainly a sad one to follow. We may be sure

that no exuberant ideality dictates British recognition of the Soviet Republic.

"Not even chivalrous sympathy

between a Labor Government and the Russian proletariat is responsible for

this move.

"Only enlightened self-interest

prompts British international policy--or, for that matter, any other nation's

foreign policy.

"Indeed, there is the only safe

basis for relationship--among the nations--and not the misguided sentimentalism

of some Americans who would make us the selfless missionaries among the

nations.

"When Great Britain recognizes Russia, it means that Britain wants and expects increased trade and

corresponding improvement for her own economic condition.

"The same argument holds for our

similar action. When Great Britain recognizes Russia, it means her acceptance of the stability of a

government that has been able for more than six years to maintain itself

against internal foes and against all manner of unsympathy and open, active

enmity from most of the powerful nations of the earth.

"It is not for the United States, born in revolution, to pass hostile judgment

upon another revolutionary government, firmly de facto and therefore

worthy of recognition as the government de jure of the Russian

people."

British recognition of Russia coincided with a period of significant events.

Lenin had died only a few days before. But the revolution he fathered went on

without him. In retrospect, the easiest part of the revolution had been the

seizure of power in October-November,1917. Then had followed the Great Civil

War which lasted, roughly, until 1920. A baker's dozen of foreign powers--the

United

States included--had sent troops into Russia, first to keep the Germans out, then to do the

Russians in. The intervention had failed, from Moscow to Vladivostok. The allies, in Churchill's phrase--had failed

to "crush Bolshevism in its cradle." But the country lay

devastated. Military communism had given way to a temporary restoration of

capitalist trading known as the NEP (New Economic Policy). The

"dictatorship of the proletariat" had been refined into the

dictatorship of the Communist Party. The Hearst press noted that Trotsky was

calling for the liberalization and decentralization of power from the party

directorate to the broader base of workers and peasants. The Russian people

were hearing of a hitherto obscure Bolshevik named Josef Stalin. And in Munich, a Bavarian citizen named Adolf Hitler went on

trial, with General Von Ludendorff as co-defendant, both charged with treason

against the German Weimar Republic.

In the United States that first week of February l924, the heart of

Woodrow Wilson expired; he had dreamed of a League of Nations which would keep the world safe for peace.

Hearst had spurned and castigated that dream as much as Wilson had spurned and castigated Hearst.But on the day

of Wilson's death, the Hearst papers and the nation paused

to mourn greatly his passing.

And then both Hearst and the nation

returned with insatiable appetite for details of the greatest scandal of

government corruption the American twentieth had yet produced: Teapot Dome. Teapot Dome,

the attempted bribery of President Harding's cabinet member, Albert Fall, by

oil speculators seeking release of naval oil field reserves for private gain.

It was a story that fulfilled all the

dire prophecies of William Randolph Hearst. For almost thirty years he had

warned that predatory monopolistic capital always sought to corrupt

government officials, and that democracy could never be secure until it had

expunged this menace from the nation's body politic.

Further: for the Hearst press, Teapot Dome helped to explain why the rulers of the American

government had refused to extend diplomatic recognition to Bolshevik Russia.

February

18, 1924, from an

editorial in Hearst's New York American:

"Revelations in Washington make it perfectly clear to the intelligent

citizen why Russia has not been recognized by the United States. The scandal in oil is only typical of the condition

to which our government and our politicians have fallen. It is the curse of

the political control by organized, rapacious Big Business..

"There is just one remedy--that is

to remove the conditions, remove the temptations which make men dishonest. Remove

the contact between government and Big Business whenever and wherever

possible.

"Whenever it becomes necessary for

a government to deal constantly with a quasi-public function like the

railroads or the telephone or telegraph companies, or the coal mines or the

mine fields, the government should take possession of them and operate them

as a public function..

"It is the kind of corruption in

government which is making America--which ought to have been the first nation to

recognize the Russian republic--the last to do so."

And Hearst's other New York paper, the Journal, piled it on:

"Great Britain and Italy recognize Russia. Shall we ride with the band or wait and hang on

to the tailboard of the calliope? Meanwhile, other nations get in on the

ground floor of Nature's greatest storehouse of resources and possibilities.

"If [Secretary of State] Hughes

can't recognize Moscow because he thinks she tried to get us to trade Uncle

Sam for a fellow with long whiskers, Mr. Hughes should have refused to sit in

a cabinet meeting with Mr. Fall, who cut more ground out from under Uncle Sam

than anybody else.

* * *

November, 1933. Soviet Foreign Commissar

Maxim Litvinov sets sail for the United States to fulfill--at long last--the Hearstian

objective of Diplomatic Recognition.. The regular features section of the

Hearst November 5th American Sunday edition, was alive with commentary

by world-known figures--something like today's op-ed articles--and

exceedingly sympathetic to the pro-Soviet view. Leon Trotsky, a protean

figure of the Bolshevik Revolution was writing from exile, whither he had

been forced and hunted down by his tenacious rival, Josef Stalin. The

headline over the Trotsky article read: "Trotzky [sic] Sees Vast Trade

Advantages in Relations Between U.S. and Soviet. Their Economic Collaboration

Would Attain A Sweep Unheard of in History." Trotsky's words followed:

"If there still remains on our planet that is torn by disorder, in the

atmosphere of new war dangers and bloody convulsions, an economic experiment

that deserves being tried out to the end, it is the experiment of

Soviet-American collaborations. In another article, novelist Maxim Gorki's

piece on Nikolai Lenin was headed: "Lenin Glowed with a Passion to

End Human Woe in Russia, Gorki Declares." And Anna Louise Strong hailed the identity of

interests--peace and trade--between the average Russian and the average

American.

But 1918 and 1933 were times with a vast

difference. Japan's conquest of Manchuria forebode its assault on China. Hitler made it clear he would re-take Germany's lost territories--and more. The Great

Depression engulfed the world. The United States had never seen such long breadlines.

Hearst had helped Roosevelt get the Democratic nomination, and become

president in 1933. But Roosevelt had alienated Hearst with New Deal regulations

and spending programs. The hard-edged Hearst of 1933 was not the horn-blowing

revolutionist of 1917. Hearst was no longer in labor's corner; he saw unions

as a threat to his newspaper empire. Taxation was driving him to the wall.

Yes, he still backed diplomatic recognition--but only if the Russians, in

return, used any money loaned to them by the U.S. to buy American goods and services. In short,

recognition was not the conferring of a favor, but a mutual convenience based

on quid pro quo.

Still, recognition of Bolshevik Russia

had been a Hearst crusade.

There was time for a subdued three

cheers and one last hoo-rah. On November 17, America recognized the Soviet Union. On November 22, Hearst's American permitted

itself that subdued editorial three cheers.

"On the initiative of President

Roosevelt," the editorial said, "the United States and Russia have

at last resumed normal relations on terms that are entirely honorable, mutually

advantageous and in harmony with 'a happy tradition of friendship' which

existed between these two great peoples for more than a century.

"As the Hearst newspapers in their

long advocacy of the restoration of friendly relations with Russia have repeatedly pointed out, friendly political

relations promote trade relations, and trade relations, when maintained on a

fair basis, promote friendly political relations.

"Consequently, the return of

Russo-American relations to normal should mean the revival of a commerce

between Russia and the United States that will greatly benefit both countries and

strengthen the ties that bind the two peoples in the same powerful friendship

which they once were proud to claim and with renewed pride they can claim

again."

(In hindsight of the acrimony that would

soon begin between Hearst and the godless Bolshevik government, the editorial

sounded almost as tortured as Peter Sellers, the American president in

"Dr. Strangelove," informing the Soviet premier that a U.S. rogue

bomber was about to incinerate one of his cities--whilst all the time

protesting his deepest affection and undying respect for the Soviet premier

and his people.)

There was, however, one big hoo-rah

left. Arthur Brisbane, Hearst's star columnist, chief editorial writer, often

regarded as Hearst's conscience, a multi-millionaire himself, but a longtime

cheer leader for the radical current in American life, Brisbane composed an essay of unrestrained joy to the

world. It was fed to 125 newspapers, both Hearst and others in the King

Features syndication. The headline on Brisbane's column in the New York American, November 19:

"Three Cheers for Roosevelt"

"Russia Recognized at Last"

"Hard Blow for Depression"

"By Arthur Brisbane

"Copyright 1933, King Features

Syndicate, Inc

"Miami, Fla., Nov. 18--At last this country decides to

"recognize" and deal with Russia. The public will exclaim:

"Thank heaven that's over."

"Russia is more than twice as big as the United States, its population is by forty millions greater

than ours, and all at work, by the way; its wealth and natural resources may

prove, under a government for the people and not for the Czars, Grand Dukes

and Monte Carlo's gambling tables, to be even greater than our

own.

"Financiers foolishly lent money to

Russia, particularly to the comic opera Kerensky.

"Now they weep because Russia won't pay. It should be remembered that Lenin,

who is to Russia what George Washington and Abraham Lincoln are

to the United

States, saw his brother die under the knout, an unpleasant Russian lash,

by order of the czar. [Poetic License. Lenin's brother was hanged for

complicity in the assassination of an earlier Czar--and did not see his

brother die.] He would not feel like paying the Czar's debts, and Lenin's

devoted disciple, Stalin, who set aside the whole calendar of Russian saints

to put the embalmed body of Lenin in their place will not pay the Czar's

debt.

Also, the Czarist-Kerensky debt to the United States amounts to only $289,073,000, not much compared

to the twenty-two thousand million dollars that Europe owes us, including interest. Concerning that debt, Europe says calmly:

"Don't you hope you may get

it?"

"And we don't refuse to recognize Europe.

"The truth is that our "Best

Minds," up to their necks in a depression of their own making, have been

afraid that Russia's experiments would succeed and put dangerous

notions in the American minds. That is why those best minds have not wanted Russia recognized.

"Russian recognition will do more

than a hundred theories to end our depression. President Roosevelt is to be

congratulated. Everyone hopes that he will enjoy and profit by his visit to Warm Springs, Georgia and come back with another idea as good as

Russian recognition."

[Here endeth the Brisbane column.]

Evidently, Roosevelt had no good ideas left. Hearst began a

long-running hatred of the President, calling many of his views communistic

and strongly implying that the President was a communist himself. Hearst

quickly developed an implacable hatred of the Soviet Union and promoted a keen interest in the good works

of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler--an admiration that would, of necessity,

end when the United States went to war with Nazi Germany.

* * *

William Randolph Hearst departed this mortal

coil in August of 1951. For more than four decades his was the most powerful

single voice in American communications. For much of his life he was, in his

own oft-repeated words, "a militant progressive," a conscientious

radical. For almost two decades he had raised his voice on behalf of the

Bolshevik Revolution.

It will forever be a closed book on how

much the government of the United States was influenced by Hearst on the question of

recognition--and how many young readers were drawn to the American Communist

Party through the sympathetic characterizations of Soviet communism in the

Hearst press. One can only salivate with speculation of how Joe McCarthy and

J. Edgar Hoover would have red-baited W.R. Hearst with guilt by association,

simply by identifying his signed editorials.

Indeed, Hearst and his Hearstlings had

already prepared a defense against charges that Hearst had been a

propagandist for Bolshevik Russia. The way was prepared as early as 1924 when

Hearst's bureau chief in Moscow

wrote:

"Five years ago, the Russian

Revolution, the vastest democratic tide which ever swept over a section of

the earth, was attacked from without by all the great military powers of the

world. Intervention stultified the normal development of the social upheaval

which rocked Russia. Instead of democracy, it forced militarism upon

the freedom-hungering people of this country. Instead of decentralization,

autonomous self-government, it imposed an absolute dictatorship of the

Central Committee. Early in 1919 this dictatorship was proclaimed and it has

remained in effect ever since."

This was the judgement of Moscow bureau chief Isaac Don Levine who, within 15

years, would be shepherding Whittaker Chambers through the State Dept with

accusations against Alger Hiss. Levine's reference to the Bolshevik

revolution as "the vastest democratic tide which ever swept over a

section of the earth" was close to Hearst's view of 1917-18. But

Levine's conclusion that it was foreign-power intervention which stultified

the Bolshevik's revolutionary democracy would not have sat well with critics

who believed that what was at fault from the start was the inherent

contractions between Bolshevik dogma and Bolshevik deeds.

Ten years later, after the glow had fled

the rose, Hearst insisted he was right all along--that the czars had been

overthrown by a Social-Democratic revolution during the first world

war--which was good--but then a minority within the Bolsheviks had usurped

power with the connivance of German militarists--which was bad. The evil ones

had betrayed Russia. What was just as reprehensible, they had

betrayed the trust of Mr. Hearst and his newspapers. And that was why Hearst

found it necessary, first, to condemn bolshevism in Russia, and second, to oppose communism in all its manifestations

in the United

States. And anyone who opposed Hearst's crusade was a Soviet dupe--or

agent.

In short, Hearst was never wrong--except

for the time when he thought he was wrong--and even then, he was wrongly

thinking he was wrong.

In his last twenty years, Hearst's

legacy was an unremitting hunt for any stirrings of communism in the schools,

libraries, churches, unions, motion pictures, book publishing, broadcasting,

government. His papers were quick to welcome Senator Joe McCarthy in whom

they recognized a kindred spirit, and with whom they traded information. It

was called the Age of McCarthyism--but William Randolph Hearst had been there

long before.

After his death, his papers came under

the control of Bill Hearst Jr. and a core of top editors. On January

15,1955, the Hearst

International News Service (INS) reported from Berlin that "William Randolph Hearst Jr., chairman

of the editorial board of the Hearst Newspapers, left East Berlin today for Moscow on a trip which he termed 'strictly journalistic.'"

The front page headline of Hearst's now-combined Journal-American was

emphatic: "Strictly Journalistic Visit" original italics).

The emphasis was reinforced by an editorial parenthesis:

"(Editor's note: David Sentner,

chief of the Hearst Newspapers' Washington Bureau, said Soviet visas for Mr.

Hearst and his party came through within a matter of days despite the

well-known and long-standing editorial opposition of the Hearst Newspapers to

communism. 'The Russians were fully aware of the long anti-communist fight of

the Hearst Newspapers when they granted the visas,' Sentner said. 'There were

no illusions about that. We were told the Communists regarded Mr. Hearst's

father as their number one American critic of the past generation.'"

The emphasis on "strictly

journalistic visit" may have been intended to assure faint-hearted

Hearst readers that young Bill was not defecting to Moscow. But the description of Hearst Senior as the

Soviet "number one American critic of the past generation" was

stretching the truth--either that, or in the best Orwellian tradition, all

library issues of Hearst papers from January 1918 through November 1933 had

simply disappeared--or never existed.

Then, in 1991, Bill Hearst, Jr.

published his memoirs and told how David Sentner suggested he go to Moscow to find out what the post-Stalin leadership was

planning. The suggestion bowled Bill over--he was sure the Soviets would

never let him in. In fact, one of his top editors predicted "the

Russians would slip some beautiful ballerina into bed with me and bingo--Siberia." But Sentner prevailed: "Bill, I

think you can break the silence of the Iron Curtain for the first time since

Stalin's death," he said, adding: "I have a hunch. Your father

campaigned against the global threat of communism ever since the first days

of the Bolshevik Revolution. The fact that he was anathema to the Commies

might be a very good reason for Moscow to give you a visa. Bill, I think they're

hurting and want to get more of their views out to the West. I believe you

may get a visa." It was clear that neither Sentner nor Bill, Jr. had

done his homework on Hearst, Sr and "the first days of the Bolshevik

Revolution," but the myth was protected once again. Hearst,Jr and his

two colleagues went to Moscow,

met the top brass, sent back their reports--and won the Pulitzer Prize.

Incidentally, Bill,Jr wrote in his memoirs that he had never seen

"Citizen Kane"--"out of principle and deference to the old

man. However, our lawyers and others who dissected it scene by scene filled

me in on the details. I feel as if I've viewed every frame." On the

basis of what he was told, Bill, Jr pronounced the film "cinematically

outstanding but morally reprehensible." It was a novel way to review a

movie.

If the "Rosebud" of

"Citizen Kane" was not the key to the core of Citizen Hearst

perhaps the Dead Hearst Scrolls of the Independence League may offer up some

tantalizing clues. The League was a minor but influential third party which

Hearst had helped found and which backed him in his struggles for high

office. Some lines from the League's platform of 1924 may illustrate the

difference between the ideal and the real in the life of William Randolph

Hearst.

"We hold that the greatest right in

the world is the right to be wrong, that in the exercise thereof people have

an inviolable right to express their unbridled thoughts on all topics and

personalities, being liable only for the abuse of that right.

"We hold that no person or set of

persons can properly establish a standard of expression for others."

table of contents

Eve’s

Magazine

|