|

Copyright ã 2003 Kenneth Koyen.

All Rights Reserved [Terms and Conditions] Snapshots of Mary Welsh Hemingway By Kenneth Koyen

|

|

|

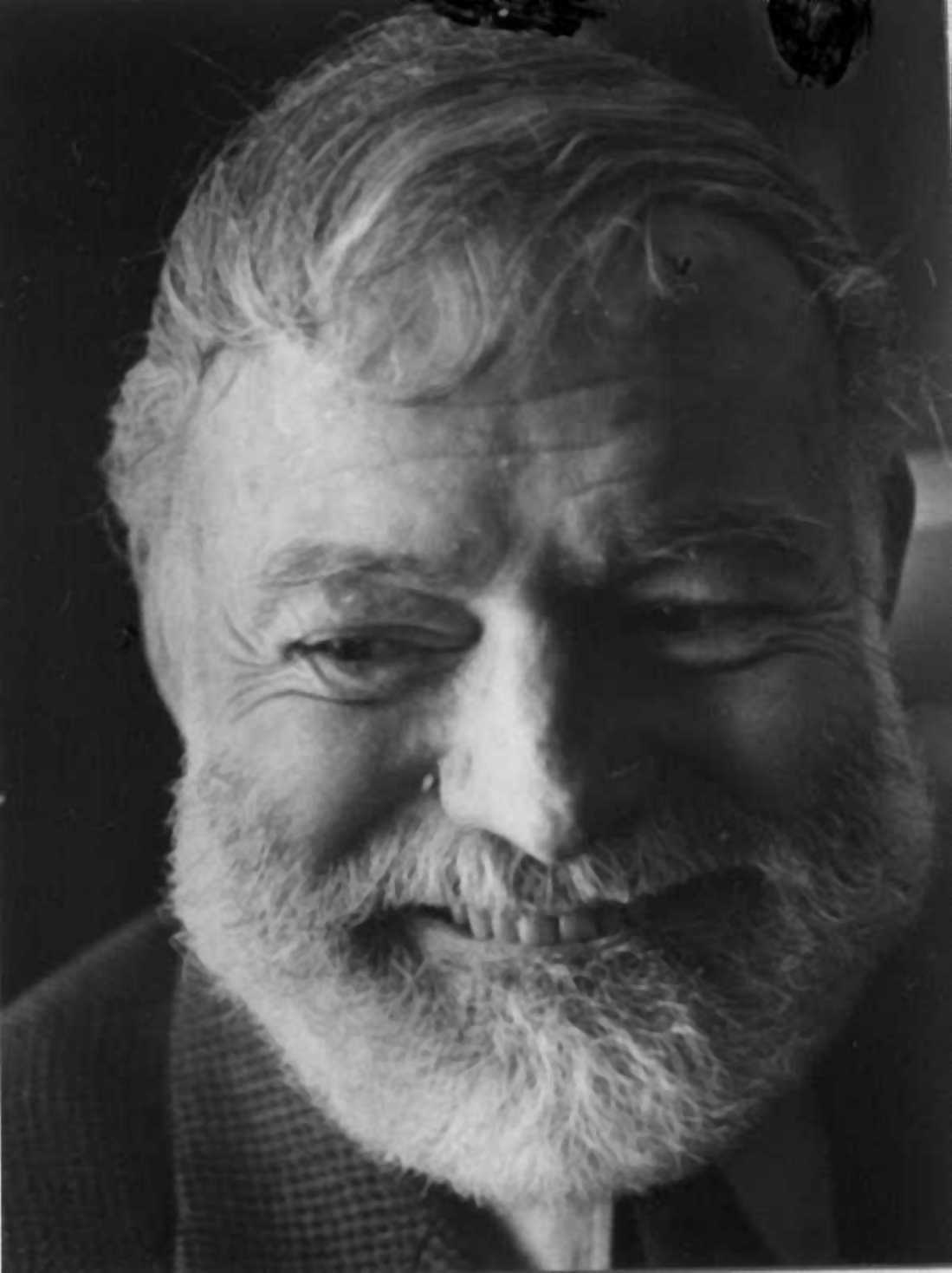

Photo by Morris Warman The legendary Ernest Hemingway.

|

Mary

Welsh Hemingway |

|

By Kenneth Koyen The first time I met Mary Welsh was

during "The Phony War." It was the spring of 1940. Eight months

before Although I had taken French language

classes in college, I was far from fluent. I decided to better myself. As my

work at the paper began in the afternoon, my mornings were free. I enrolled

in a French language class for foreigners given by the Alliance Francaise. It

was held in the Sorbonne. I found about 20 people in the class. Most of them

were Poles who had fled the German invasion of their country. They appeared

to have the means to re-establish their lives in a new venue. One woman did not appear to be part of

the Polish group. She was not. She was American. We introduced ourselves. She

said that she was Mary Welsh and that she was a correspondent for the London

Daily Express at the paper’s I learned later that she was 32, the

daughter of a She landed a job at The Chicago Daily

News writing womens’ page stories. On a holiday trip to As our French classes went on we merely

nodded at each other. We did not chitchat. We gave our attention to our

instructor, an attractive young French woman who spoke English as well as she

spoke French. I cannot certify that our French improved markedly. But I do

know that the classes ended abruptly on May 10. Then the German Army launched

its assault against the Allies. "The Phony War" was over and the

world learned a new term, "Blitzkrieg." With the fall of I looked up a friend, Will Lang. He was

running the re-established bureau of TIME and I was introduced. I said,

"Hello," to Mary and reminded her that we had met as fellow

students. She briefly acknowledged the fact. I got the impression that she

did not wish to discuss any relationship with other men, no matter how

innocuous, in front of Hemingway. During the luncheon, Hemingway commanded

the conversation, I listened eagerly for a memorable quote that I could

retell. There were none. Their talk was about story coverage, past and

future. Mary had left the Daily Express. She and Hemingway were each

writing for TIME and As the talk continued I learned that

Hemingway was grandly billeted at the Hotel Ritz. It also became evident that

Mary was sharing his quarters. Mary’s maiden and writing byline name was, of

course, Mary Welsh. But her correct, legal, name was Mrs. Noel Monks. She had

married Monks, an Australian journalist, not long after she first arrived in Mary had met Hemingway in As the war continued Mary busily filed

her stories to TIME. But not long after our luncheon she attracted far more

attention from what she said than from what she wrote. She accused Andy

Rooney and two other correspondents of plagiarism. Rooney was then a staff

writer and war correspondent for the Army’s newspaper, The Stars and

Stripes. Rooney, who had met Mary several times, was astounded. The charge that he stole a story and words

from her copy still rankles Rooney. Today he says, "It’s just not

anything I would have done." The longtime, irascible sage of television

adds, "This was one of my earliest claims to fame." In 1945, a year after Hemingway and

Welsh began their lives together, Gelhorn divorced Hemingway. Mary managed to

divorce Monks in 1945, seven years after their marriage. After the war

Hemingway and Mary continued their adventurous celebrity existence together.

They traveled widely. He wrote his novels to popular and critical acclaim and

honors. They lived in his house in Before their marriage a woman friend of

Mary’s, who had had an earlier affair with Hemingway, spoke to Mary. The

friend warned that Hemingway could be "beastly." According to The

New York Times, he had once described Mary as "a useless, smirking

war correspondent," and "a scavenger." He once threw wine in

her face in front of friends. He once smashed her typewriter. The Times later

described her wedded existence as a "bruised life." They remained together even as matters

became more difficult for Mary. Hemingway began to decline mentally. He

suffered from delusions. He had a considerable fortune, but he feared

needlessly that his banker was mishandling it. Hemingway thought that the

U.S. Government had agents, including the FBI, shadowing him about

non-existent tax fraud. Because of these and other episodes,

Hemingway was examined and treated by physicians and psychiatrists. He was

taken to institutions, including the Mayo Clinic, and received a series of

drastic electro-shock treatments. Against Mary’s wishes he was released from

the Mayo Clinic and returned home to Ketchum. Early on the morning of The sound woke Mary. She left her

bedroom and raced down the stairs to find the body. She reported to the

police and press that Hemingway had shot himself accidentally while he was

cleaning his gun. She wrote later that she did not know why she said that. A.E. Hotchner, a writer and a frequent

companion of Hemingway, wrote that he could not fault Mary for covering up.

Hotchner thought that Mary was unprepared to accept what had happened and

unable to explain it. "What difference does it make?" he asked. Her

instinctive reaction was understandable. Suicide might tarnish the image of

the powerful writer, the fearless adventurer. Hemingway had once offered Dorothy

Parker, the wit and writer, a better word than "Courage." It was,

he said, "Guts." He defined "Guts" as "Grace under

pressure." But there was no "Grace" in suicide. It could be

seen as surrender and a final act of defeat. The police and the coroner ruled

that Hemingway’s death was suicide. Mary passed the following years writing

her autobiography, "How It Was." It was published in 1976. It might

well have been subtitled, "The Importance of Being Ernest’s Wife."

Overlong at 537 pages, it stressed passages of affection and love. On a lower

key, the difficulties, including those of the last years. The "it"

in the book’s title referred, of course, to life with Hemingway. Without

Hemingway the book could not have been written. If it had, it would not have

been published. Mary moved to In her last few years she became an

invalid and seldom left her

|

|