|

Riding the Rails By Larry Stessin |

|

|

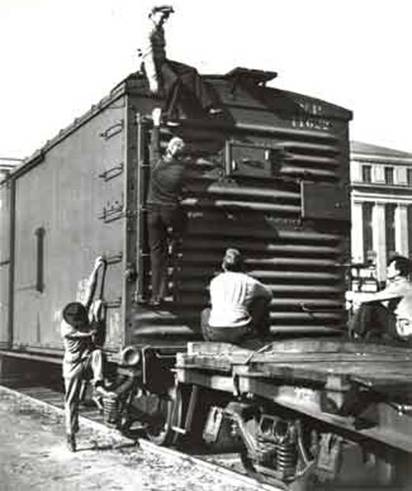

Courtesy of the

National Archives In the depths of the Great

Depression, hoboes climb he catwalk of a passing freight, circa 1932. |

Walking the rails.

Photo by John Vachonx Hopping a freight train in search

of the elusive dream. |

|

Riding

the Rails By Larry Stessin "One evening as the sun went

down The In song and story the American hobo

was a true romantic, a knight of the open road who crisscrossed this country with a

pack on his shoulder and a few coins jingling in his jeans. He was drawn as a free

spirited rover dedicated to a simple world of milk and honey. To ballad

makers Hobohemia was a fanciful guitars and "bazoo blowers" whose

harmonicas, corroded with tobacco juice, made raucous music to the accompaniment of grinding

wheels and hissing steam. It was this false romanticism that lured me to ride the rails rather than sell apples on a

street corner during the depression of 1932. It was a very dark night when I approached a

stationary freight train on the west side of Once the train settled down to a

steady speed I crawled towards a vacant corner and joined the snoozers. It was daybreak

when the shadows I first saw when I vaulted the freight car turned into two

dozen seedy-clothed men sprawled on a floor covered with

straw and old soggy newspapers pounded

into the shape f pillows. I experienced no anxiety in my new environment,

having seen and hooted box car bums since I was a sixth grader. When the train stopped near and ran for a nearby stream to splash water on

their stub-grown faces, refill their bottles with fresh water and scurry back

to the choo-choo. Others remained in the car to indulge in a tipple or two

out of smudged covered flasks. The hoot from the engine gave me enough time

to scoot back and three from our clique showed the agility of trapeze artists

in hurdling into the boxcar while the train was picking up steam.

At the end of the first week, I was well up-and-up on the routines of

hobo life. Surprisingly, I learned

that few rod riders began their "careers'' with the objective of being

constantly on the road. For the most

part their initial goal was to take a long trip to nowhere in particular and

return home after having sated their

craving for wanderlust. But, in short order their money dwindled to smaller

and smaller coins and the knowledge that the depression seemed forever made

getting a job back home "pie in the sky" – all adding up to their

continued itinerary. Getting food other than by stealing from a

mama-papa shop, or an A&P store which

often displayed its fruits and vegetables on sidewalks, was a daily

challenge. In cities,

an honest-to-goodness hobo would shun the missions run by the charities or

by public agencies. The chief beef was

the long waits, the large number of

drunks on the line and the complete corruption of mother's tasty cooking. The

number one no-no was the Salvation Army which often required the hungry to

work several hours washing floors or dishes before being fed. I

hit upon a technique that rarely left me without supper and often enough for a bite the following morning. I would walk

down a street of middle-class, homes and look for a driveway with two or more

cars in it. These were the days of a

very fragile economy and two cars in every garage was a myth. To me more than

one auto parked by the house meant that the residents were having guests for

dinner. 1 would walk into the backyard, ring the bell and when someone

appeared at the door, in louder than my usual voice would ask, "Do you

have any work for a young hungry man?" Few folks were so hardened as to

shoo me away while the guests pressed their noses against the windows to catch

a glimpse of the sad voiced beggar. Soon, out came a sandwich or a plateful

of food which I gobbled down while sitting on the porch steps. My

other most important daily need was to

find a safe place to sleep. An empty cattle

car which sometimes could accommodate over fifty riders was always a

Godsend. Sometimes there was room

enough to squeeze into a space where a car could be carrying some freight or

livestock. Other than that there were three alternatives – all dangerous. One

was to wedge oneself beneath the iron rods underneath a car. Another was to

swiftly scoot up a ladder and stretch out on

the boards on top of the speeding freight carrier and sleep as the

train pitched from side to side. Or,

if one chose a passenger train, the place for a hobo to sleep was standing

between the blinds, with elbows bent around the rods which held the

thick, black leather shades - barriers

against a howling wind.

My mind was constantly concerned

where to find safer places to sleep. If mileage and a specific destination

was not a goal there were always hobo

jungles where one could nap to a warming fire. However, hobo jungles were

always at the mercy of the local police or the railway patrolmen. It was the hobo grapevine from

"bo's" coming and going which provided what was safest. Jails. It seemed that almost every town or farm area had vagrancy laws, legislation to keep the unwanted, the

shiftless, the beggars from besmirching the image of hometown. The average

penalty if caught and convicted was three months in jail. That was a hefty sentence for a

restless tribe to take. From the rumors and gossip in the boxcars there was

endless talk that vagrancy laws were not being enforced in most of the

country. Cities and towns by the hundreds – because of the depression, did

not have the will or the budgets for

the shiftless by jailing them for

months at a time. This was music to my ears and one day I decided to put this

good news to a test. My testing ground happened to be Dearborn,

Michigan where Ford cars were built. I decided to take the bold approach

although the policeman I walked up to did not need any tutoring to see that I

was not a native. I shuffled up to him and asked for a handout "for a

cup of coffee.'' He grabbed my arm

and escorted me to a jailhouse a few blocks away. The warden took over and shoved me into a cell in

which there were three others. I was surprised at the appearance of the jail.

It was spotless. The walls were wallpapered and an aroma of sweet smelling cleanser filled

the room. The warden ordered us to a corner of the cell. He then lifted a

thin mattress from one of the cots and said, "This is Henry Ford's town,

the cleanest in the country. And this

jail is the cleanest in the country.'' And with that comment he shook the

mattress vigorously and said, "See, no mice, no lice." He seemed

pleased at how he poetized the two words. I later learned that Henry Ford was

a spirited community citizen who often preached the sermon that Dearborn should

strive to be the cleanest city in the nation. He sometimes visited the jails to make sure

that the decor did not spoil the region's look. The next day I was let out, hustled into a paddy

wagon which made the rounds of the

other jails for other bad eggs, like me, dumped at the county line and

admonished never to return again. When I returned to the

"jungle'' and told the others

that the vagrancy laws were

indeed unenforced, they chimed in that they were receiving similar amnesty in other parts

of the country, but minus the grandiloquence. I had found at least one way to get

a night's sleep without the terror of injury or worse. When I ended my hobo safari I often

felt that the romance I had envisioned was no more than a long tiresome

hitchhike. Lawrence A. Stessin, an alumni of the New York Times

and Forbes Magazine, was the former editor of the Silurian News. Shortly before his death, he confided to me

that he had "killed a man" who jumped him in an open box car when

he had fallen asleep eating a sandwich.

As Larry struggled with his knife-wielding assailant, the attacker

fell backward out of the box car. When

the train pulled into the next town, Larry learned that a body had been found

beside the tracks. – The Editor |

|