|

The Wit and Wisdom of the Mafia By Selwyn Raab |

|

|

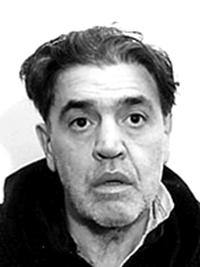

Vincent “The Chin” Gagante, a New

York Mafioso notorious for wandering the streets of New York in his bathrobe,

simulating madness. |

Carmine Galante, a Bonanno family

potentate gunned down while lunching at a restaurant in Bushwick, Brooklyn. |

|

The Wit and Wisdom of the Mafia By Selwyn

Raab

Another approach

occurred on Sullivan Street in Greenwich Village. I attempted to chat with

Vincent "Chin" Gigante whose relatives insisted that he was a

mentally distressed, punch drunk ex boxer, not the underworld titan of the

Genovese crime family. Two beefy companions of Mr. Gigante almost trampled me

as I scurried to safety. I did squeeze a

memorable rejoinder from James Failla in the 1990s while researching a story

about his role as the Gambino family's not-so-secret controller of the

city's private garbage carting industry. Known as Jimmy Brown for favoring

that sartorial shade, I intercepted him on his way to a weekly meeting with

supplicant carting contractors. Failla uncoiled a terse

rejection:" Eat (an expletive rhyming with hit.)" Covering Cosa Nostra

means you're on your own. All that is required is perseverance and a

disregard for insults. I stumbled into the beat through a side door. In the

1960s, I was handling sedate education stories on the old World Telegram and

The Sun when a school construction scandal erupted. There was stark evidence

of crumbling roofs, shoddy work and renovations that endangered the safety of

thousands of students and teachers. Combing the backgrounds of the

building-trades companies unearthed a pattern of phantom investors, rigged

bids and bribes to school officials. Much of the malfeasance was engineered

by behind-the-scenes Mafiosi. Later as a reporter for

the Telly, WNBC, PBS, and The Times, I kept running across Cosa Nostra

fingerprints on numerous aspects of government, law enforcement, the judicial

system, unions and everyday life. It required little sagacity to determine

that, by the 1970s, the Mafia operated a surrogate state in the New York

metropolitan area. Unfortunately, for much of the 20th Century New York's

governmental authorities were largely indifferent to these criminal inroads.

The majority of media editors were of a similar mind. They preferred reporting

on the occasional sensational homicides, internecine wise guy wars and

colorful gangster celebrities in place of costly, long-range inquiries to

document the Mafia's economic clout and manipulation of government agencies. At The Times, which I

joined in 1974 to cover criminal justice and governmental misdeeds, the Mafia

was generally regarded as an unrewarding assignment. It was viewed by most

reporters as a career dead-end with scant prospects for landing plum

promotions. I inherited the beat with the proviso that I would pursue

non-Mafia investigative stories and that mob reporting would focus on their

stranglehold over vital economic interests. It was a wide arena, including

the construction industry, union racketeering, garbage carting, the Garment Center

and the Fulton Fish Market.

The easy part of the

Mafia saga is waiting for arrests and relying on the customary spin from

prosecutors and investigators. The reconstruction of a major undercover case

can be intriguing but it is one dimensional. Lawyers for accused Mafiosi are

equally predictable, normally spouting uninspired, boilerplate denials. Uncovering background

material to flesh out the culture, motivation, tactics and underlying

sociopathic elements of the American Mafia was the ultimate challenge. After

all, the Cosa Nostra prides itself as being a secret society and most efforts

to mingle with their stalwarts were rebuffed. Fortunately, persistence can

pay off. One dividend came from

Anthony Accetturo, the admitted head of the Lucchese family in New Jersey in

the 1980s and 1990s. In his teens, Accetturo used a crutch to batter

opponents and was dubbed "Tumac," after a ferocious caveman in a

film, "One Million BC." Upon learning that his new bosses wanted to

whack him, Tumac defected, suddenly eager to recount his experiences and explain

why he had switched sides. A friendly New Jersey official arranged

prison interviews with Accetturo and "Tumac" provided rare insight

and scoops about the history and the strength and weaknesses of the American

Mafia.

|

|