|

Farewell to Mac By Dennis Duggan |

|

|

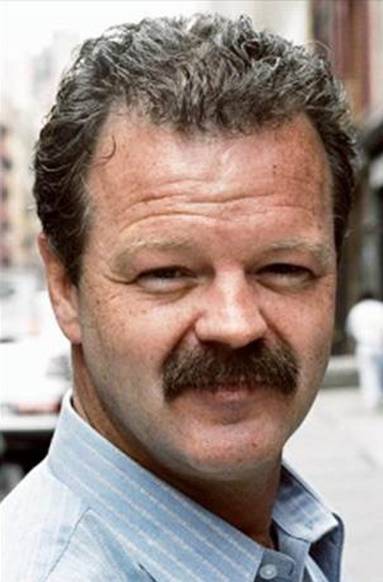

The great Mike

McAlary. |

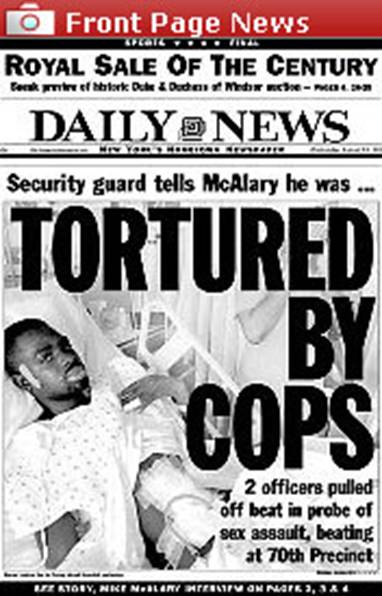

McAlary's revelations

of police torture that stunned a city. . |

|

By Dennis Duggan Mike McAlary wrote almost every one of his

columns as though he were going to be hit by a truck. That was a dictum set forth by

Murray Kempton, one of McAlary’s idols. They were as different as

night and day but they were bonded by their passion for

newspapering. I spent many days and many nights in

McAlary’s company, the days were in New York Newsday’s city room on He died on Christmas Day of cancer.

He was 41. A few months earlier in a heart-breaking scene in

the New York Daily News City Room he acknowledged the cheers of his

fellow reporters and said that he hoped he would live long enough to see his

children grow up and to be able to walk on the beach with them. Tears flowed that day and last

December 25th at Charlie Sennett, who worked with McAlary

at both the New York Post and the Daily News, recalled his days working

alongside McAlary who the Times said was "the city’s dominant tabloid

reporter of the last decade," wrote this moving tribute

to McAlary. "So Mac is gone. I’ll never forget

being a young cop reporter at the Post and the News and being able to claim

him as a friend. "I’ll never forget the

way he ran his finger down a small, black book of contacts

and told you exactly which detective to call in “I’ll never forget how

he liked to sing at Elaine’s. "I’ll never forget his

stamina." Sennett, now with the Boston Globe,

recalled being up all night at a cops’ social club in "Kriegel (Daily News sports

columnist Mark Kriegel) and I would be a mess sleeping on the floor or

the couch and Mike would be up early reading the papers and making his

calls." Best of all, says Sennett, was when

McAlary complimented you on a story. "The story rocked," he would

say. I know just how generous Mac was first

hand. I covered the trial of John

Wayne Bobbitt and his wife Lorena in a The day after the trial I got the only

interview with her at a nail salon where she worked. She did my nails as we talked and at one

point dug her little paring knife too

deep into my cuticle. "Ouch," I exclaimed. In my lead, I wrote that I was luckier

than her husband. My hotel phone rang that day. It was Mac on the phone

laughing and telling me, "That really rocked!" But it was Mac’s cop reporting that

began at New York Newsday that attracted attention. He was hired by the

newspaper’s editor Don Forst who had first hired him to work as a

high school sports reporter at the Boston Herald American in 1980. "He had the fire,"

Forst

who is now editor of the Village Voice told me. "He had passion for his

work and he had fun doing it," said Forst who

tried to convince McAlary to stay at the paper promising him that he would

become a columnist. "That was the year we brought Jimmy

Breslin over from the Daily News. Mac saw an opening at the

News and went there to become a columnist. It was a swap." I hated to see McAlary leave the paper.

He was a throwback to the earlier days of the two-fisted, hard drinking reporters of my era.

I don’t think McAlary spent a day of his life in a health club running to nowhere. He was too

busy soaking himself in the city’s brine and becoming the kind of breaking

news writer who left the rest of us with our mouths hanging open. When he left New York Newsday he wrote

in his first book "Buddy Boys," which was about police corruption

in the 77th police precinct in "To

Dennis, "It’s your

town. "They’re

your streets. "I’m just

renting. "All the

best. "Your Friend,

Mike McAlary " In writing this tribute I talked to friends

all over town including the many he made in the New York Police Department.

He forged a special and rare relationship with people in law enforcement,

many of whom are suspicious of most of us in the

press. I sat in Greg Lasak's office on the

third floor of the State Supreme Court Building on Besides Lasak, the number two man in

Queens District Attorney Richard Brown's office, there were former

Police Commissioner Ray Kelly and John Timony, now police commissioner in Abner Louima stood alongside one aisle

of the church with the Rev. Al Sharpton. It was McAlary's impassioned and exclusive

accounts of Louima's alleged torture in 1997 at the hands of cops in the 70th

precinct in "In some ways," said Mac,

"this had been my biggest cop story. Almost like homering in my last at

bat. It had changed the case, and it had changed the city somewhat. It had

changed me a little, too." At the time he wrote the Louima stories

he was dying of colon cancer of which

he said; "The Cancer life, I have discovered, is not unlike waking up on

death row. "Ordinarily, I'm not bitter or even

panicked. I'm fine so long as I don't obsess too much on the possibility of

never being a grandfather to my 12-year-old son's kid or missing my 10-year

old daughter's wedding or being unable to teach my 5-year old boy how to

throw a curveball." He finished writing his first

non-fiction book, "Sore Loser," and was hard at work on the second

book when he died. His friends are said to be working to complete that

book. I noticed a copy of "Sore

Loser," about a He pulled the book and opened it to show

me the salutation Mac had written for him at a party in Elaine's held shortly

before his death. It read: "For Gregory, my special

and gallant friend. "You have showed your humor and

intelligence across the years. Your friend, Mick McAlary." Lasak had been at the hospital just a

week before Mac's death. It was now a matter of time for the great reporter

who was surrounded by his family and friends. "He went into the shower and I said

goodbye to him and he waved goodbye to me," said Lasak who had presided

over some of the most sensational trials in I asked Lasak what was it that had drawn

McAlary to the cops and the cops to him. Cops, as former First Deputy Police

Commissioner John Timoney said, don't usually like reporters. "Most cops

look down on newspaper reporters," said Timoney, a tough cop from Lasak confirmed those remarks by Timoney

adding that "He had an aura about him. And he was trustworthy. He

wouldn't hurt you just for a story. Detectives took to him and they have to

rely on their instincts in their work. He was the kind of guy who looked you

in the eye and he never misled you." "He was brash and he was cocky but

under all that he was a sincere man who loved his work. Right up to the end

he was breaking our onions. He was being Mike." He was still being Mike when young

Newsday reporter Al Baker went to see him in the hospital a few days before

his death. Baker, who had worked with McAlary at

the Daily News, admired the columnist for his round-the-clock work ethic, and

for his smarts. "He was always saying to me,

'C'mon, let's go!" Baker recalls. "He had his computer hooked up to

the Internet and he said 'this makes you smarter.'" At the hospital, Baker was told by

Kriegel not to show emotion at Mac's bedside. "Mac reached his hand out

to me and said 'I love you' and then he whispered, 'Go, be great.'" Just being Mike. |

|