|

Jack Newfield: From the Radical Outpost By Eve Berliner |

|

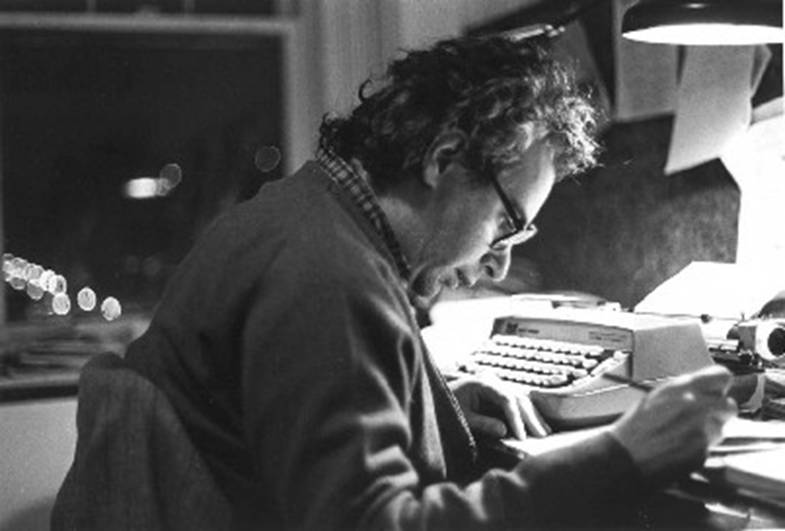

An intense, young Jack Newfield at work, 1973. By Eve Berliner An enemy of corruption, subjugation,

exploitation, a pugilistic street fighter for the abused, Jack Newfield is a

journalist of sacred rage. His constituency is the victims,

underdogs and rebels of this earth. He has taken on the likes of Don King,

Louis Farrakhan, Edward Koch and the judicial establishment of the City of That profound sense of injustice came

early to this child of Bedford-Stuyvesant, His mother struggled valiantly, never

quite recovering from the loss, never remarrying or ever having a date. Her

mandate was to work. By the time Jack entered Public School 54, she was slaving away five days a week in a department

store in downtown They were essentially the last white

family on the block, the suspicion of authority innate, the alliance with the

powerless forged. * * * It was to be Jackie Robinson who would

inflame and inspire him, Jackie Robinson who came up to the Dodgers in 1947

when Newfield was nine years of age, a fanatical Dodger fan, reading about

him day in and day out, Robinson who would prevail with daring and heroism

and pride in the face of vilification. "He was the first outsider/underdog

I identified with. "Eight years ahead of the Supreme

Court's ruling, baseball was integrated in a ballpark that was walking

distance from my house in 1947. And I read the Post. I read Jimmy

Cannon every day and saw the bigotry, the discrimination – bean balls,

exclusion -- that was all directed at Robinson. People resenting his

existence in the Major Leagues. "The first time I ever saw him play

was on "I had a deep identification with

him and with * * * The great journalistic influences came

early. "The best thing that ever happened

to me was discovering the Jimmy Cannon/Murray Kempton New York Post

when I was nine years old. They made me want to become a journalist. " "Cannon in the 40's was a great

liberal. He crusaded for Jackie Robinson even before he came up to the

Majors. He was able to humanize all these black athletes for me as a kid,

reading about Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson. He was a poet of the city, of

Broadway, of "I.F. Stone was the first model of

investigative journalism. I discovered him in college. To me he was like

Sherlock Holmes. From him I learned you've got to read all the documents,

read all the transcripts, annoy the bureaucrats to give you the memos. Read,

read, read. That was the lesson I took from Stone. "Later it was Mailer. I was deeply

influenced by Norman Mailer's journalism. Mailer was a founder of the Village

Voice when I went to work there. I had read his fiction and knew that

Mailer went to Boys High, my own high school, and I was very aware of him. He

graduated in '41, I graduated in '55. When he started to write journalism, Advertisements

for Myself and The Presidential Papers and his famous Esquire

piece about the Democratic National Convention -- I still think that it's the

single greatest piece of magazine journalism I've ever read -- it was called

"Superman Comes to the Supermarket" about JFK's nomination in 1960. It was the first piece that

caught the * * * Mississippi -- the heart of darkness --

summer of 1963, Jack Newfield, part idealist, part anarchist, part innocent,

on the frontlines of struggle. "The summer of '63 was very scary.

Houses were getting firebombed. Blacks were afraid to drive in a car with

whites. This was the year in which Goodman, Cheney and Schwerner

were killed. " "By 1965 things were a little less

tense. I got chased a few times and filed a complaint with the FBI." * * * Newfield had been drawn in to the civil

rights movement by his best friend, Paul DuBrul.

They became involved in organizing the "Youth March for Integrated

Schools." He literally marched on "It was the first time I ever heard

King speak. And that day King spoke about voting rights. And King blew me

away. This was April, 1959." By February, 1960 he was involved in

sit-ins at Hunter College where he was studying journalism and working in a

little office on 125th Street organizing support demonstrations for sit-ins.

"Met Bob Moses there and Bayard Rustin."

In 1962, he began writing pamphlets for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating

Committee (SNCC]. By 1964 he was writing about these

matters on the pages of the Village Voice. Newfield returned to "I spent a lot of time in * * * The assassination of the dream -- John,

Martin and Bobby -- came hard to Jack Newfield who had come to love, to know

deeply as friend and biographer (then in progress) of Robert Francis Kennedy. June 5, 1968, Jack there in the ballroom

of the Ambassador Hotel when the moan rose like a wave across the room -- men

and women weeping and praying, wailing, pounding the floor -- and Bobby was

dead, the last hope of America gone. "Though it's really unknowable, I

think that if Bobby had lived to be President we would have ended the Vietnam

War much sooner, renewed the war on poverty; we would have had a totally

different policy toward blacks than Richard Nixon had. Kennedy was still a

work in progress when he was killed -- just 42 years of age, King 39 when he

was killed. Could have been around together another 30 years on parallel

tracks." The friendship was a great treasure. Lingering memories: "The joy in

people's eyes, particularly Mexicans and blacks when he came through their

neighborhoods. He used to let me ride in his car with him during the "I think it was the murder of his

brother that was the defining event of his life. After that he identified

with anybody who had a hurt, a loss, and when he got elected to the Senate he

became a moral witness to poverty." "With King I didn't quite grasp

that he was the greatest American of the 20th century when he was alive and

it's only through the course of time that I now have come to understand how

amazing King was in his capacity to grow and his ability to stay sane in the

late 60's when so many people around him were going nuts, becoming terrorists

or dropping out or getting into drugs or hating America or giving up on

integration. King never lost his commitment to an interracial society, to

democracy, to non-violence, to reason." * * * For Jack Newfield, the sport of boxing

has always been a kind of paradox of brutality and art. "I've always considered boxing a

guilty pleasure," he states. His explosive 1995 book Only in

America: The Life and Crimes of Don King is a scathing portrait of

the flamboyant, brutal and corrupt boxing promoter and the dark corrupt

underworld of boxing. "I now know a lot of fighters who

are almost all black and Latino who have been exploited. I view fighters as

exploited workers, uneducated, like the farm workers of the 1960's and the

miners of the 1930's. Fighters are the only athletes without a labor union. Baseball, football, basketball, hockey, all have a union.

They're victimized and exploited by the promoters and I view my writing about

boxing as another way to defend the working class against the rich

plutocrat." "Sugar Ray Robinson was the

greatest fighter who ever lived. When I met him late in life he talked to me

about how much he hated fighting. In 1947 he killed an opponent in the ring

in Of Ali: "Hurts my heart whenever I

see him. I see him pretty regularly at events and I give him a hug and he

taps me on the chin and my heart breaks because I know all the punches he

took in fighting and in the gym contributed to his condition."Sugar

Ray Robinson had Alzheimer's, Joe Louis had dementia

and Ali. The three greatest fighters who ever lived all ended up with tragic

medical conditions. It's like a curse. "I'm very ambivalent about

boxing." * * * Newfield pleads guilty to the suspicion

that he is on more than a few hit lists: slumlords, labor racketeers, nursing

home operators, arsonists, errant politicians. "Sued by Farrakhan for $44-billion.

Thrown out of court. "Koch [City for Sale: Ed Koch

and the Betrayal of New York City, 1989] is the one who really

tried to hurt me by trying to get me fired repeatedly when he was Mayor. Even

tried to buy the Voice to fire me. Sued me at the Post about

three years ago. "Don King screams and yells. Has a

lot of bluster, calls me bad names. "The judges -- they hate me. I've

written the Ten Worst Judges list eight different times. Four of them sued. All

dismissed before trial by other judges. "Never been sued successfully. I'm

very careful." * * * And so after a journalistic reign at the

Village Voice from 1964 to 1988 as a reporter, columnist and senior

editor, a brief but wonderful two and a half year stint as a columnist and

senior investigative editor at The Daily News, he resigned on

principle as a member of management to support the striking workers in 1990.

"In some ways that was much harder to do than going to As for life at the Post under

Rupert Murdoch [October '91 to present], "I only met him once in my

life. I'm forever grateful that I have the freedom to write columns that

dispute the whole editorial section. I can write ten columns knocking D'Amato

two years ago or criticizing Giuliani or Pataki or Newt Gingrich or Clarence

Thomas when the editorial page is supporting these people. And I'm very, very

grateful for that. To my amazement the Post gives me more freedom than

the Village Voice did at the end." Jack Newfield and his family have

resided in Jack Newfield, in the end, a muckraker,

a voice of conscience, a voice of sacred rage, in the tradition of Murray

Kempton, his guiding light. |