|

The Old Grey Lady: The Way It Was By Robert D. McFadden |

|||||

|

New York Times The

grand entrance to the venerable old lady. |

New York Times Street of memory |

||||

|

By Robert D. McFadden

Look at the twirling,

surreal clock hands if you like. There’s really no need. You can tell the

deadline looms by the savage shouts of the men, by the crescendo of

thundering typewriters and jangling phones, by the fever rising in this

cavernous newsroom of iron gray and bare steel in Midtown Manhattan. Through the haze of

cigarette smoke, you can see reporters cradling receivers and pounding Smith-Coronas

and Royals; shirt-sleeved copy editors, a few in green eyeshades, hunched at

horseshoe desks; important men conferring under the windows and college boys

hurrying up the aisles to roars of “Copy!” You can feel the

place vibrate, a plunging roller-coaster, and the great presses underground

have not yet begun to rumble. It is a Friday evening, May 19, 1961, my first

night as a copyboy at The New York Times. I have just turned 24, and while

I’ve been a reporter at three stepping-stone newspapers, I am terrified and

thrilled at being — at long last — in this exotic setting of disciplined

chaos. If the center of the

world is the third-floor newsroom of the venerable Gray Lady at 229 West 43rd

Street, its epicenter is an unimposing, waist-high desk called “the post,”

with a railing that separates the ranks of reporters from the bailiwicks of

editors. It’s a symbolic barrier, but as I will learn, most things at The

Times are symbolic as well as real: rarely do careers here cross the

reporter-editor divide, with the exception of the top editors, nearly all of

whom are former reporters. Sammy Solovitz, a

growling, chain-smoking, 4-foot, 9-inch tyrant who is the boss of the

copyboys, presides at the post. His fingers are stained yellow, and he has

the darting suspicious eyes of a jailer. “Co-py!” someone shouts

from the maelstrom. “That’s you kid,” Sammy

rasps through his cigarette. I am suddenly part of

the action, earning my $45 a week. I rush out for the copy Charles Grutzner

has just ripped out of his machine. He does not look up. He’s already banging

away on another take. What I retrieve is just

a fat paragraph, and it’s not written on a single piece of paper, but on a

10-part “book” — an original copy (my favorite oxymoron) and 9 flimsies

separated by carbons. In a deft snapping motion that is surprisingly hard to

learn, Sammy tears the book apart for distribution to the editors. The

original goes to the backfield and the copy desk. From the post, you can

survey much of the block-long newsroom. It is a shabby Valhalla, with

soot-streaked, 17-foot ceilings cluttered with beams, pneumatic tubes and a

bewildering maze of ducts, pipes and suspended lighting fixtures.. The walls

are battleship gray below, and dingy beige above, an uneven line. The décor

is functional: calendars, clocks, maps, bulletin boards, filing cabinets,

fire extinguishers. The concrete floors are

covered with grayish-yellowish tiles streaked with an effluvia of crushed

cigarettes, spilled coffee and tobacco spittle. There are no ashtrays, and

the edges of desks are mottled with burns. Brass spittoons are long gone, but

wastebaskets serve the curmudgeons. The whole place is adrift in paper:

tottering in stacks, skewered on spikes, littered over the floors, heaped on

desks. The newsroom, I quickly

discover, is an archly formal workplace. Everyone is addressed as Mister,

Miss or Mrs. The men wear suits and neckties, though they are mostly rumpled

and askew. There are no time-clocks to punch, but no one arrives late or

leaves without an editor’s “Good night.” Reporters are summoned over an

intimidating loudspeaker that booms: “Mr. Manley! Report to the City Desk!” Bylines, always rare in

The Times, are still reserved for senior writers or exceptional reporting

efforts. They too are stilted. It’s Robert, not Bob; Thomas, not Tom. And the

paternal Times, not its children, will decide what to call writers in print:

A.M. Rosenthal, not Abraham M. Rosenthal. Assignments and

instructions are given with no-nonsense severity: polite, but no questions

please. The newsroom wears a cloak of old-fashioned gentility, and as later

becomes clear, it masks a great deal — the bottle in a drawer, the poker game

at the back, the gift-wrapped cases of liquor at Christmastime. But it also

covers an undercurrent of ruthless competition and an uncompromising

intellectual honesty. The general news

department in 1961 is a nearly exclusive bastion of white men. Edith Evans

Asbury and Laurie Johnston are among the few women on the local staff outside

the realms of food, society and women’s news. But newspapermen still talk of

Anne O’Hare McCormick, the pioneering foreign affairs correspondent, who won

a Pulitzer in 1937 and died in 1954. There are only three

black men in the newsroom now: Layhmond Robinson Jr., a reporter covering

politics; Theodore Jones, a general assignment reporter, and Robert

Claybrooks, a news assistant on the city desk. Black men in white gloves take

you up and down in the elevators, the cafeteria has black and Hispanic workers

and nearly all the porters who clean the premises overnight are black. The newsroom is a

hidebound hierarchy, and where you sit (if you sit at all) signifies your

rank and is as important as any title. Star reporters are arrayed like saints

across the front: Homer Bigart, Peter Kihss, Foster Hailey and Murray

Schumach. They all reside on one side of a line of pillars; the rewrite bank

on the other side does not count, although it is vital and highly respected.

The unseen heroes are Times correspondents in Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin

America, in Washington and across the nation. Behind the city room

stars, an army of talented reporters, also seated in order of rank, stretches

away toward 44th Street. They work at steel desks whose central feature is a

disappearing typewriter bolted to the underside of the desktop; it can be

rolled up to work on, or down into a hidden well. It is monstrously heavy;

you could lose fingers if it slips. Chairs are the swivel type, although Mr.

Schumach prefers an uncomfortable straight-back chair because, he says, it is

less likely to be stolen. Further behind the city

reporters, back by the 44th Street windows, glass-topped partitions stake out

territories for specialized news departments: culture, financial-business,

sports, ships and aviation. There are cubicles for the critics — Brooks

Atkinson, Harold C. Schonberg, Bosley Crowther and others. And there is a

niche for a bevy of writers who compose the hourly radio news bulletins on

WQXR.

New York Times The old

Sunday Department responsible for the weekly Magazine, Book Review, Drama and

News of the Week in Review sections. On the 43rd Street side

of the post, the newsroom editors camp at islands of steel desks shoved

together for the city, national and foreign news operations, each with a

U-shaped copydesk as an appendage. Nearby are the picture and soc-obit desks.

Besides society news and obituaries, the latter handles theater reviews, news

of the arts and other odds and ends. Frank Adams, the city

editor, is pointed out to me. He is a portly, florid man responsible for 200

reporters and editors and a news report heavy on municipal affairs and

written with plodding fidelity to facts and figures, but with little flair

for the literature of journalism. I’m told that good staff writers, including

Gay Talese, chafe under the yoke. In a year, after my apprenticeship as

copyboy, news clerk and news assistant in various departments, Mr. Adams will

send me a note saying I’ve been promoted to the reporting staff. In a corner behind the

archipelago of editing desks is the inner sanctum of Turner Catledge, the

managing editor. Around his office is a little railing that fences off his

bullpen of assistants. It is the O.K. Corral of senior editors empowered to

dictate the content and placement of major news in The Times. These gunslingers

include Theodore M. Bernstein, Lewis Jordan and Robert Crandall — a cabal of

largely anonymous men who, given the gist of the top 20 stories from around

the world, will draw up a front page in two minutes, showing the historical

perspective, relative importance and relationships of the day’s news. They

make marvelous sense of it all for millions, including news editors across

America. Scanning further along

the 43rd Street side, there is the radio room, where crackling receivers

bring in the transmissions of the city police and fire dispatchers, and

reports from the Coast Guard, from ships at sea and other news sources,

including short-wave broadcasts from foreign capitals around the world. In the southeast corner

is the wire room, the nerve center of telegraphic operations. More than a

million words come through this room every day, and 185,000 of them are

printed in The Times. Here are Telex machines carrying messages to, and

dispatches from, 30 Times correspondents around the world, 23 Washington

reporters and scores of reporters and stringers across the country.

Here, too, are batteries

of teletype machines pounding out the bulletins and daily budgets of The

Associated Press, The United Press, The International News Service, Reuters, Agence

France-Presse, Tass and other global news services. The AP alone has a dozen

machines. Several more carry reports from Washington, and a cable is reserved

for London bureau traffic, which serves as a funnel for news reports from all

over Europe, the Middle East and Africa. At the horseshoe-shaped

copy desks, slot bosses in the center distribute copy to editors on the rim,

who bend over their labors with a lifetime of skepticism, making liberal use

of black pencils to slash away excess verbiage or rewrite flabby leads,

scissors and paste pots to rearrange paragraphs, and copies of Roget’s

Thesaurus to craft headlines that will fit in The Times’s narrow columns,

eight across a page. To many reporters, copy

editors are fussy grammarians, sticklers for spelling and butchers of copy.

To many editors, reporters are careless louts obsessed with adjectives. It is

only a cultural abyss, one of many on the paper. The truth is that reporters

and copy editors are more alike than they admit. All are well-read if not

well-educated, students of literature, history, political science, economics,

the law, arts and sciences. And they are guided by impartiality, fair play

and common sense. As I look around this

room, I ask myself: Do I have what it takes? My journalism degree from the

University of Wisconsin seems less important than my experience on The

Wisconsin Rapids Tribune, The (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal and The

Cincinnati Enquirer. I’ve been hired by Richard D. Burritt, an assistant

managing editor, at a time of transition in journalism, with an aging

generation of largely self-taught generalists, many of them two-finger

typists, giving way to college-educated men and women with specialized

talents and presumably broader visions. But most of us must begin humbly. I and the other

copyboys, constantly on the run, carry the edited copy from wire baskets on

each copydesk to a set of pneumatic tubes at the east end of the newsroom.

The tubes look like something out of an anatomy textbook: veins and arteries

soaring up, separating, disappearing into the lofty ceiling. I meet the clerk in

charge of the tubes, an Ivy Leaguer in a three-piece suit with a Phi Beta

Kappa key on a gold chain across his vest. He has degrees from Harvard and

Columbia, speaks three languages and is just now drawing a map of Africa,

freehand, with national boundaries and capitals. My ambitious heart sinks as

he rolls up the copy I’ve given him, puts it in a cylinder and sends it away

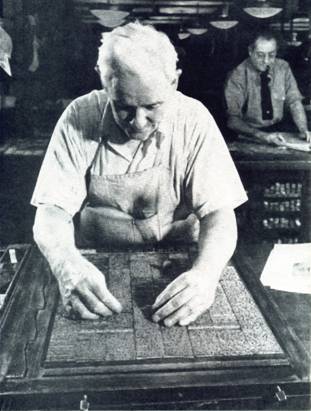

— whoosh! — in a burst of suctioned air to the fourth-floor composing room. After the deadline,

Sammy takes me up to see where the tubes come out. We ride in a tiny elevator

— a vertical coffin with room for two that often carries three or four,

groaning slowly between the white-collar third floor and the blue-collar

fourth floor, yet another in-house cultural divide. The door opens at the

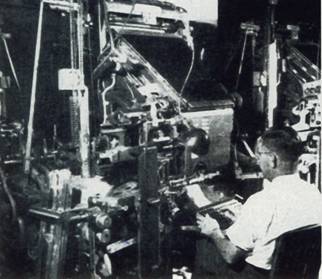

composing room and we spill out into another world: a Martian landscape of

Mergenthaler Lineotypes where printers like pianists play bizarre keyboards

(“etaoin shrdlu”), casting words into hot type, set backwards a line at a

time until a tray is assembled for the inked galley proofs and the page

lockups. The non-words “etaoin shrdlu” are the first 12 keys in two rows at

the keyboard’s left; they’re used to fill out a garbled line of type,

indicating it should be discarded in a “hellbox.”

Nearby, ink-stained

proofreaders sweat under the lights, trying to catch errors. It is hard to

imagine how they concentrate in all this noise and activity — a din of

clattering typesetters, the swirls of rushing people, mallets banging on

steel frames. It is a muscular place, governed by strange customs and alien

terms, and I try not to stray far from the elevator. But just a few feet from

the door, I am able to watch the final work on the Page One lockup. All the

elements of the front page — the type for articles and headlines, the

photo-engraved picture cuts, the weather and edition information that flank

The New York Times logo at the top — are set into a steel frame, called a

chase, atop a waist-high table known as the stone. Dave Lidman, a makeup

editor with a kindly face, motions me over and takes some of the mystery out

of the operation. He checks the whole page, reading type that is upside down

and backward. If he spots an error, he does not touch the type. It’s against

the union rules for an editor to handle type, he explains, so he must ask a

printer to make fixes. When Dave is satisfied, the frame is tightened with

blocks of wood and screws. Mallet blows are struck to ensure that the type is

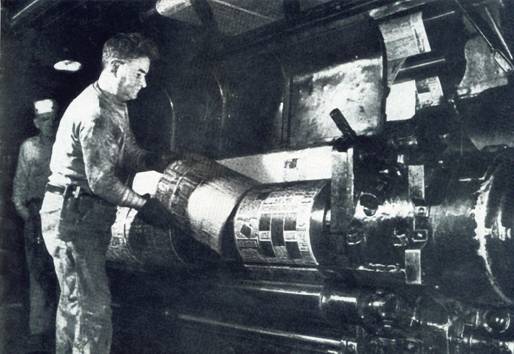

level and nothing is loose. Then, Dave explains, the

locked page is wheeled to a matrix operation, where a cardboard-like mat is

pressed down on the locked-up type with enormous force — 2,100 pounds per

square inch — under a cylindrical roller. The mat, a positive image of the

page, is dropped down a chute to the stereotype room five floors below. There, the mat is curved

into a half-barrel shape and molten lead is sprayed against it. The resulting

metal plate is an exact replica — in negative again — of the page set in type

in the composing room. The plate, when cooled in a bath of water, is fitted

onto a cylinder of the press. Paper rolling over the inked plates will pick

up the positive image.

New York Times A

pressman placing the stereotype plate on the press. When all is ready, the

pressmen stand back, a bell rings, a button is pushed and the gargantuan

presses, fed by great rolls of newsprint and tons of ink, begin to roll. The

noise is deafening. Indeed, many pressmen are congenitally deaf. Soon the

paper rolls are speeding at 1,200 feet a minute, and the presses are churning

out 400,000 newspapers an hour. It is a two-part paper, averaging 60 pages on

weekdays and a whopping 436 pages on Sundays. The first edition is in.

There are two more and a postscript to go before the night is over. Back in the newsroom, an

eerie quiet has settled in, as if a storm has passed. Darkness has walled in

the windows. The phones are silent. Many reporters have gone, but the rewrite

bank and the copydesks are still manned. The newsroom is a mess. Wastebaskets

overflow with crumpled paper and cardboard coffee cups. Brown stains snake

over desktops. Cigarette butts carpet the floor. Sammy sends me and

another copyboy down to the mail room for bundles of the City Edition now

rolling off the roaring presses in the subterranean dungeons. You can feel

the vibrations in the mail room, a droning, reverberating hall of conveyor

belts and frenetic activity. It is just off the lobby and conveniently next

to the bays where the trucks wait to be loaded for deliveries to homes,

newsstands, train stations and airports. The weekday circulation is nearly

700,000, and double that on Sundays. A grouchy mailer warns

us to stand back from the conveyor belts and scoops up armfuls of papers for

us. They are warm and smell of newsprint and fresh ink that immediately rubs

off onto our hands. We carry them up and distribute copies to all the

reporters and editors. A rewriteman sends me

scurrying for clips on a big-shot who has died. I trek west down a long hall

that comes out in the morgue, an enormous, brightly-lighted room packed with

filing cabinets that rise to the ceiling and run back to a vanishing point.

At the counter (“No Admittance!”), I fill out a request for the morgue

attendant, who disappears into the stacks. Soon, he returns with a file

folder jammed with tattered, yellowing clips on the dead big-shot. “Okay kid,” Sammy says

when I get back. “You can go out for the papers now.” He means the other

papers — The Herald Tribune, The Daily News, The Daily Mirror, The New York

Post, The Journal-American and The World-Telegram & The Sun. He gives me change to

pay for them, and down I go again, in the elevator, through the marble lobby,

past the guard and the cluster of press agents and other news addicts waiting

for papers hot off the presses. Out in the cool night air, I breathe in the

truck fumes and the illusory romance of the city. Down at the corner,

Times Square opens like a jeweled kaleidoscope: a blaze of moving neon

lights, the Camel billboard blowing smoke rings, marquees advertising sin,

the madrigal of traffic played by Father Knickerbocker, the crowds of

tourists and pickpockets, preachers and three-card monte sharks. Chubby

Checker is doing the newfangled twist at a club across the way. At the crossroads of Broadway

and Seventh Avenue rises the Times Tower, the paper’s home from 1903 to 1913.

It’s a slender, beautiful skyscraper, but puny compared to the “annex” that

became the Times’s historic 20th Century headquarters, a 14-story pile of

stone and steel with a mansard roof that somehow blends an architecture of

indestructibility with the graceful lines of a French chateau. News bulletins in

running lights trickle around the fourth-floor exterior of the Times Tower.

At its base is a newsstand plump with local and out-of-town papers. I buy

copies of the local competition and head back. A night editor quickly scans

them and clips stories we’ve somehow missed. There are always a few. The

cuttings are handed out to rewritemen, who will work the phones and chase them

down for the later editions. By 2 a.m., all the exclusives are broken. At 2:30, I and another

copyboy are assigned a final task by Sammy: to gather up and bundle every

scrap of reporters’ notes and wire copy in the newsroom. We pack it all in a

giant ball, tie it with string and haul it to a storage room for a month or

two of safekeeping. It often happens, I am told, that the old notes and wire

stories are needed to verify or correct published material. By 3 a.m., the skeleton

staff is given the “Good night!” As we step out into 43rd

Street under the white “Times” globes, Sammy, a rewriteman and a few editors

head across the street to Gough’s, the watering hole of Timesmen. I’m invited

along. Despite the late hour, Gough’s is still busy. We mingle with

compositors, pressmen and other lobster shift stragglers, many wearing square

hats crafted from sheets of tomorrow’s Times, some “talking” in sign

language. Over a couple of beers

at the bar, the day is rehashed, the old stories are retold. For my part, I’m

filled with awe at this day. It’s hard to grasp how the paper has come

together — a million words, the work of thousands, all churned into an

erudite rendering of yesterday’s world, and against the deadlines. I’m

exhausted, but feel good about what’s ahead. A world of possibility has

opened up. The Times — this institution, this idea, this place of steel and

stone — seems indestructible. But who knows? Note:

This article first appeared in Ahead of The Times, an in-house Intranet site

of The New York Times. |

|||||