|

Copyright

(c) Maury Allen 1999. All Rights Reserved. [Terms and Conditions.] Jackie Robinson: An American Hero By Maury Allen LOS ANGELES DODGERS

Jackie Robinson takes off from third and steals home in one of the

most dazzling feats of World Series history! Game One, The 1955 World Series,

8th inning, the

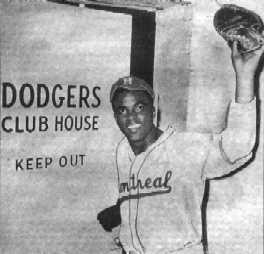

Jackie Robinson reporting to the Brooklyn Dodgers from the minor

league Montreal Royals, 1947.

|

|

By Maury Allen The game of baseball is about runs, hits

and errors, 70 homers by Mark McGwire and seven no hitters by Nolan Ryan, a .367

lifetime mark by Ty Cobb and 511 wins by Cy Young. It is about more than 15,000 people who

have made it to the big leagues from Hank Aaron in alphabetical order to

Dutch Zwilling over the last 130 years of organized record keeping. It is about people who get an instant

moment of fame, not even Andy Warhol's 15 minutes, such as Moonlight Graham,

a one gamer for the 1905 New York Giants until W.A. Kinsella made him famous

in Field of Dreams, and Walter Alston with an at bat for the Cardinals

in 1936. Only a Brooklyn Dodger World Series win in 1955 and a brilliant Hall

of Fame managerial career saved him from lifelong obscurity. It is also about the recognition of the

judges, the writers of baseball and the recognition of the peers, the players

of the game. Half a century ago, in 1949, that all

happened for a man named Jack Roosevelt Robinson, a figure of momentous

standing in American history. He was named to the game's highest honor, the

Most Valuable Player in 1949. Robinson was not just about baseball. He

was about equality, about decency, about morality, about injustice, about

ending a wrong with a right after more than 60 years of Kids across the country, well back into

the last quarter of the 19th century, dreamed of playing big league ball as

they hit rocks with sticks on city lots and farm fields, college parks and

neighborhood lots, cement school yards and grassy diamonds. Only white kids

could make that dream live. Black kids could only hawk their athletic wares

in Negro leagues. Then along came a man named Branch

Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers who wanted to right that

wrong and make a little money along the way. On Rickey had tried out his plan a few days

earlier on the famed radio baseball announcer Red Barber, a son of "I'm going to sign a black

man," Rickey told him. "I'm going to quit," Barber

told Rickey. Barber's wife, the mother of his

daughters, had other ideas about the economy of the Barber household without

the "Think about it," Lila Barber

said. Barber thought about it, agreed to stay

on the job, became even more famous and richer after Robinson arrived in

Ebbets Field and announced years later how much he liked and respected the

future Hall of Fame Brooklyn Dodgers second baseman. Economics is what it was all about in

1945 when Robinson signed and again in 1947 when he finally made it to the

big club in There were grumbles about playing with

the black man from southerners Hugh Casey, Dixie Walker and Bobby Bragan.

There was support from a New Yorker named Ralph Branca, a Californian named

Duke Snider and a Kentucky Colonel named Harold (Pee Wee) Reese. Reese, who died at his "This was in October of 1945 and I

was on a ship coming back from Navy duty in the South Pacific," recalled

Reese. "One of the radio operators came up to me and told me the Dodgers

had just signed a nigger ball player. I didn't react much. What I

cared about was getting home, back to my family and back to baseball." The guy came back to Reese a few minutes

later and blurted out, "The Nigger ball player is a

shortstop." Now Reese cared. He would soon be back at shortstop in Others helped too, including the

southern manager Clay Hopper, who first told Rickey he would rather die than

manage a black. When he saw how Robinson hit, fielded, threw and especially

ran, he fell in love with him. Robinson joined the Dodgers after spring

training in No mention of race. No mention of

history. No mention of the reactions of Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther

King, Lena Horne, Joe Louis or, for that matter, Harry S. Truman, President

of the United States. A Negro was now on the roster of the

Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team. There may have been dancing in the streets of

|

|

What if this guy with the black

face, pigeon toed walk, big body, squeaky voice and perfect diction fell on

his bottom? What then? A lot of guys came along who couldn't hit big league

pitching, danced away from curve balls, lost their feet in the bucket at home

plate, couldn't cover ground in the field or choked when the count was 3-2

and the lead runner was 90 feet away. What then, indeed? Robinson failed to get a hit in his

first big league game off Johnny Sain, the right handed half of the famed

Boston ditty, "Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain," in reference to

the skills of Warren Spahn, the game's winningest lefthander and Sain, a

tough starter and later a tougher reliever. Then a few hits came, a few stolen bases

and some fine fielding plays at first, a position he had never experienced

before. The racists sent the hate mail, screamed from the stands and called

out obscenities over an anonymous hotel telephone. That's the way it had

always been for blacks, hooded men in the night, rarely one on one in

reasoned discussion about who it was that made people white or black after

all. Things got hot when the Dodgers played

in "That meant so much, so much,"

Jackie Robinson told me years later. "It was just a kind and incredible

gesture." "I took some heat about it when I

went home to Things turned. Robinson began getting

more hits. He started running wild on the bases and Robinson batted .297 with 29 stolen

bases that first year. He was named the winner of the Rookie of the Year

award, the highest honor for a new player in the game. The award now bears

his name and when players receive the Jackie Robinson Rookie of the Year

award they understand the history. The Dodgers won the pennant that year

and played the Yankees in the World Series. They lost in a bitter seven game

Series but Robinson was the talk of the town, the way he hit, fielded, ran

and led his team, only a few months after fighting off hate mail and death

threats. He was like most second year players in

1948, a little too cocky, a lot overweight from banquets (also a movie of his

life), a little too anxious to cash in on his sudden success. He managed to

hit .296 after a slow start, stole only 22 bases and missed out on the World

Series as the Braves ("Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain") lost out

to the Cleveland Indians. A black man named Larry Doby starred for

the Indians, the second black in the game, and the most famous Negro League

player of all time, Satchel Paige ("Don't look back, something may be

gaining on you") pitched in one game at age 42 or 46 or 48, depending on

the story Paige was telling that day. Fifty years ago, 1949, was Robinson's

most brilliant season. He was 30 years old that season, far older than most

third year players in the history of the game. He peaked with a league

leading .342 average and 37 stolen bases. He beat out the great Stan Musial,

who hit .376 the year before and .338 in 1949 and swept the MVP title 50

years ago. What was most significant was that the

honor was gained on the field, had nothing to do with Robinson's birthright

and almost ended discussion about race for the rest of his playing days. Robinson was a fading star in 1955 when the Brooklyn Dodgers finally won a World Series over the Yankees and quit after a lackluster 1956. He had been traded to the Giants over that winter but had already decided he had enough. He left with a loud roar, a controversial article announcing his retirement in Look Magazine. |

|

He was inducted into the Hall of Fame on

Jackie Robinson died on His legend took off again in 1997 as the

50th anniversary of his arrival in the game was celebrated. Numerous books

and articles about him appeared. His widow, Rachel Robinson, stepped forward

to remind a new generation of his legacy. Baseball honored his memory by removing

his uniform number 42 from the back of any other player in the game's future. Fifty years ago he was the MVP of

baseball. There is a strong case to be made that

Jackie Robinson was the game's ultimate Most Valuable Player.

|