|

Arthur Schlesinger Jr: A Son Reflects By Stephen Schlesinger |

|

|

Doug Hall Photography Stephen Schlesinger and his beloved father, Arthur

SchlesingerJr. |

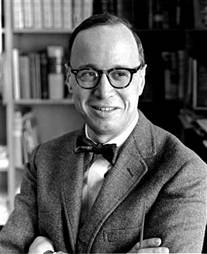

Arthur Schlesinger,

special assistant and “court historian” to the Kennedy’s, 1961.

Photo by Art Rickerby Arthur and Jack in a

moment of contemplation, the White House, July, 1962. |

|

By Stephen Schlesinger My father, the late historian Arthur

Schlesinger Jr., might have seemed like the classic, bow-tied, cloistered,

academic, but he secretly yearned to be a journalist. He was brought up in a

family in which teaching American history was the main business, a tradition

begun by his father, Arthur Schlesinger Sr., who was one of the leading US

historians at Harvard University. My father faithfully followed his father

into the same field, joining the Harvard history department after World War

II in his mid-20s, despite never earning his Ph.D. Yet throughout his life,

he was attracted to the work of reporters. This was not entirely surprising

as his own father was active in the Neiman Fellows, an organization that

brought newsmen to Harvard for a year. My father felt that journalists, with

their fingers on the pulse of the nation, had interesting, rough and ready,

careers, leading cosmopolitan and intriguing lives, often more so than academics.

“The Front Page” was his favorite movie. And, from his historian’s

perspective, reporters were all writing the first drafts of history. He had an extraordinary circle of

friends in the journalistic community. They included such luminaries as his

Harvard classmate and best-selling author, Teddy White, The New Yorker political

writer Richard Rovere with whom he wrote a book about Truman’s firing of

General Douglas MacArthur entitled The

General and the President as well as other New Yorker worthies

like the golf analyst Herbert Warren Wind, John Hersey, Edmund Wilson, EJ

Kahn and Elizabeth Drew; columnists like Joseph Alsop, James “Scotty” Reston,

Walter Lippmann, Rowland Evans, James Wechsler, Murray Kempton and Mary

McGrory; editors like The Washington Post’s Ben Bradlee, The Boston

Globe’s Tom Winship, Time

Magazine’s Henry Grunwald and Newsweek’s Oz Elliott and John

Meacham; Washington Post publishers Phil and Katherine Graham, and TV

anchors like John Chancellor and Walter Cronkite, and many others. He encouraged all of his sons to go

into journalism (though not his two daughters). My younger brother Andrew was

a reporter for The Nashville Tennessean and The Rocky Mountain News

and later a producer for ABC’s Close-Up. Today he is a freelancer. My

youngest brother, Robert, was a one-time reporter for The Boston Globe’s

Washington office and is now editor of the Opinion page of The US News and

World Report website. As for myself, despite having a law degree, I

started free-lancing for The Village Voice after graduation. Later I

founded and edited my own magazine, The New Democrat, a monthly

publication on the liberal-left of the Democratic Party in the late

1960s. Eventually I

gravitated to becoming a columnist for The Boston Globe writing the

.“L’terary Life” column. At one point, my father tried to redirect me to The

New York Times but in my youthful arrogance I forsook a chance to serve

as deputy to Harrison Salisbury as he was setting up the NY Times

Op-Ed page. Later I worked for Time Magazine. In 1978, I briefly

reported on politics for The New York Post and worked on editorials

with Rupert Murdoch who was then promising to keep The Post a liberal

daily. In the 1990s, I became publisher of the quarterly publication, The

World Policy Journal. Though my father was well-known for

his scholarly works, he, in many ways,

practiced journalism almost as much as academics. In his extra hours,

away from teaching and book-writing, he wrote movie reviews for Show Magazine,

contributed articles to Life Magazine and Vanity Fair and Esquire,

served as a monthly columnist for The Wall Street Journal, The New

York Post and other publications, and regularly wrote Op-Ed pieces for a

variety of newspapers. Through his work as a speechwriter and aide to Adlai

Stevenson, full-time Special Assistant to John Kennedy in the White House,

later as an occasional advisor to Robert Kennedy and Democratic presidential

candidates ranging from George McGovern to Walter Mondale to Bill Clinton to

Al Gore to John Kerry, he kept abreast of the central issues of his time and

wrote incisive commentaries on them. He sought out newspapers and magazines

that reached the largest audiences in order to have the widest impact on the

national debate. Part of the enjoyment he took in this arena was stirring up

verbal fisticuffs over his views. Toward the end of his life, in his late

80s, he learned how to blog and added commentaries for the Huffingtonpost.com

to his editorial arsenal. Oddly enough, within his own

academic career, such worldly ventures earned him quizzical stares from his

professional colleagues. Many fellow scholars felt that it was somehow

demeaning or improper for a highly influential and respected professor like

my father to write for popular publications. This attitude carried over, in

some respects, even to the success of his best-selling books about such

celebrated presidents as Andrew Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt, and John F.

Kennedy. Certain academics regarded the bravura reviews, enormous sales, and,

on at least two occasions, Pulitzer Prizes he received, as proof of

unscholarly work. But he never cared what his colleagues thought and he never

flinched from playing a public role. He wanted to be an authoritative figure

in the American marketplace of ideas, both as an observer and participant. He

did this for over seventy years. He became a historian/journalist in the

finest sense of both words. |

|