|

Son of Sam and the Long Hot Summer of 1977 By Owen Moritz |

|

|

NYPD Mug Shot Son of Sam, David Berkowitz, the .44 Caliber Killer who

terrorized New York City during the summer of 1977, and murdered six young

people. |

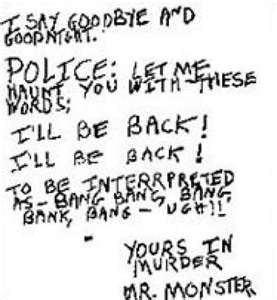

NYPD Police File The first Son of Sam letter to Captain Joseph Borrelli of the

New Yorik City Police Department. |

|

The rampage of murder comes to an end. |

|

|

Son of Sam and the Long Hot Summer of 1977 By Owen Moritz It may be hard to believe today, but in the summer of

1977 New Yorkers feared for their very lives. A serial killer was

preying on young people. In slightly

more than a year he killed six people, wounded seven others. No one knew what

he looked like and the descriptions from survivors were so sketchy that each

new composite drawing bore little resemblance to the previous one. We weren’t

even sure if we were looking for Jack the Ripper or Jill the Ripper. There

had been suggestions the killer might be a woman. I was among a number of Daily News staffers writing

speculative stories on the police manhunt for someone calling himself Son of

Sam. In my case I was getting feeds from Bill Federici and Pat Doyle at

police headquarters. Meanwhile, columnist Jimmy Breslin was working his own

sources. We all knew certain things about the killer—he stalked

couples in secluded parking spots, used a .44 caliber revolver and fancied

pretty girls with shoulder-length dark hair. Thousands of women were so

terrified they cut or dyed their hair blond or made a run on blonde wigs at

beauty supply stores. Moreover, there was the manic boast that put everyone on

edge. He sent wild notes to Police Captain Joseph Borrelli and Breslin.

“Sam's a thirsty lad,” he wrote Breslin, “and he won't let me stop killing

until he gets his fill of blood.” In the early morning of Ten days later, on The news travelled fast. We awaited an official press

conference. But 1977 was an election year and Mayor Abraham B. Beame,

fighting for his political life, wanted to be on hand for the announcement.

That meant nothing definitively until after Meantime, rumors of an arrest were swirling and I was

told to start writing. Like a mirage, the news room filled up with veteran

reporters, offering their services for one of the great news stories of that

or any era. Editor Mike O’Neill arrived from his home in O’Neill promptly bumped Bill Umstead, the night

assistant managing editor, from the news slot—a humiliation the late Umstead

never forgot. Some minutes later, into the now busy and humming news room,

came a police officer in uniform, escorting a black youth. He asked to see O’Neill. “He was driving your car,” the

officer told the editor. “Do you know him?” “Yes,” O’Neill said. “He’s my driver.” More facts were coming in from Doyle and Meantime, it occurred to me that in the pell-mell fury

of writing we didn’t have the suspect’s name from police. I turned to Brain Kates, in the next seat, who

was phoning everyone he knew in “Do you have a name for the perp?” I asked. “Yes,” he answered. “David Berkowitz.” It was one of those jarring moments. Any name is possible. But Berkowitz? I knew

a few people named Berkowitz and none of them was a serial killer. Finally, well after Back in the news room, O’Neill shouted, “Keep writing.”

Pages were added to the news hole to make room for sidebars and pictures. My lead remained unchanged. (“A 24-year-old, gun-loving

mailman was arrested late last night as Son of Sam, the .44 caliber killer

who has terrorized New York for more than a year and murdered six young

people. ‘Well you got me…’”). But inserts and urgent updates were added

through the night. Staff members called the victims’ families for

comment. When we got information that

Berkowitz may have grown up in the Glen Oaks section of Another mystery was solved. Where did Berkowitz get the

weapon? He had served with the Army in A front page proof came up. A copyeditor, Harry

Demarsky, didn’t like the headline—thought it had Berkowitz arrested and convicted-- and so told O’Neill.

The editor redid the headline to its iconic state: NAB MAILMAN AS .44 KILLER. We learned how police broke the case. A vigilant

dog-walker had come forward four days after the Bensonhurst attack and told

police she remembered seeing a cream-colored Ford Galaxy parked illegally

near a fire hydrant. The killer

“looked right in her face,” a detective said. Berkowitz’s car had been

ticketed and detectives were able to trace the ticket back to Berkowitz’s At Dawn came up through the big windows of the The Son of Sam edition flew off the newsstands. The Daily News had been selling fewer than

2 million copies a day since the mid-1970s, down from the highs of its

halcyon days. But it’s a safe guess the paper sold more than 2 million copies

on In the end, Americans saw a paunchy, nerdy-looking man

with a disturbing smile who had set off the greatest manhunt in city history.

Berkowitz admitted to some of the crimes, but not all. He claimed members of

a satanic cult were involved. While some experts put credence in his claims,

no other persons have ever been charged. He contended he got his orders to

kill from neighbor Sam Carr’s black Labrador retriever—hence his Son of Sam

moniker. Reputed to be a model prisoner, Berkowitz is serving life in prison. A postscript. Dreary news stories exploring Berkowitz’s

upbringing, drug use and demons ran for days without relief. Then, six days

after his capture, on |

|