|

Through a Glass Darkly: Memories of Bloody Sunday By David Tereshchuk |

|

|

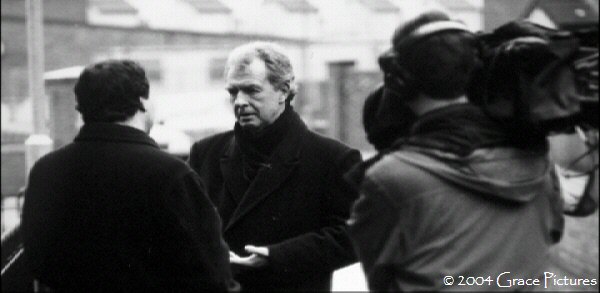

Michael

McHugh/Grace Pictures David Tereshchuk, eyewitness to the 1972 Northern Irish massacre known as Bloody Sunday," during the making of a documentary film exploring his memories. |

|

|

Domingo

Sangriento/Bloody Sunday A gripping moment from "Bloody Sunday," a film my Paul Greengrass, which relived the slaughter of 14 Catholic civilians by British soldiers during a protest march in the City of Derry more than 30 years ago. |

January, 1923. An African-American home in Rosewood, Florida burned by a rampaging lynch mob. The entire community of Rosewood was destroyed. Estimates of mortalities range from eight to several hundred. |

|

By David Tereshchuk How did I really get here? What’s

my true history? How did the past I call mine actually happen? Not long ago I was summoned back to my

old home country, the United Kingdom, to give eyewitness evidence at Tony

Blair’s Tribunal of Inquiry into a Northern Irish massacre that happened over

thirty years ago – the "Bloody Sunday" of January 30th,

1972, when British troops killed fourteen Catholic civilians during a protest

march in the city of Derry. I’d been a callow 23 year-old when I

covered the march and the resulting carnage for British television. Decades

later, I thought recalling the details was not going to be too difficult –

essentially it would be, even taking into account the passage of time and

some haziness that would naturally have set in, just a mechanistic matter of

getting the old grey cells to order up what I could remember and then putting

it in order. It turned out to be altogether more

troublesome – and I wrote about the discomforting experience for the New

York Times Sunday magazine. The paper headlined the piece "An

Unreliable Witness" – which didn’t endear me to Times editors - and an

insightful film-maker, Michael McHugh, tracked me to Derry and back to

produce a remarkable documentary with the same unflattering title. Now,

though, "an unreliable witness" is a label I have come to make

peace with. The whole endeavor started in me a set

of ruminations on the process of journalistic recall - and other modes of

recollection, too - that are still not fully resolved. I was tripped up by a detail. My mind’s

eye told me a soldier I had seen firing in the direction of my section of the

crowd had been wearing a red beret (the distinguishing mark of the Parachute

Regiment, the crack troops who had been unexpectedly ordered into action) but

most of the pictorial evidence, both newsfilm and photos, suggested he must

have been wearing a helmet. I ended up thoroughly confused. I consulted several noted experts on

memory and eyewitness testimony. One of them, psychology professor Elizabeth

Loftus of the Universities of Washington and California, later told me how I

had probably "superimposed" one snapshot recollection over another

in the tumult of gunfire. During the hearing itself one of the three judges

on the Tribunal panel pointed out to me there were other (beret-wearing)

soldiers photographed in the near vicinity, whom I could have been recalling.

Overall, the uncertainty did not detract substantially from the thrust of my

testimony – that the shooting had been unprovoked. But the questionable

recollection surely bothered me. And it was to prove only the beginning

of a widening arc of uncertainty for me and a humbling appreciation of how

little I understand the process by which experiences – especially traumatic

experiences – can work on a reporter’s, or anyone’s, developing

consciousness. I didn’t think at the time that Bloody

Sunday had any special effect on me. I’d already experienced a horribly

one-sided and atrocity-filled war when Pakistani troops savagely attacked

civilian populations as well as some overwhelmed freedom fighters struggling

for the territory that eventually became Bangladesh. And in my first year in

Northern Ireland I’d become accustomed to firefights and being held at

gunpoint by paramilitaries. But soon, as with many in my generation

of reporters who won spurs in "The Troubles" (a typically wry Irish

euphemism, quick to catch on, for the violence) my career took me into other

areas besides those beautiful but scarred Six Counties. I became a Third

World enthusiast, roaming internationally, and across Africa especially.

That’s not to say that I didn’t ever return to Northern Ireland, but whenever

I did, something … and during those years I couldn’t have told you what …

kept me away from that grim stretch of Derry’s Bogside district that had

become a killing field. When, with the turn of the century, the

call for my testimony came up, and the filming of McHugh’s documentary, I

finally met another eyewitness. It was Don Mullan, who had been a fifteen

year-old marcher on the fateful day, and was later catapulted to prominence

when his researches into suppressed testimony (compiled in a 1997 book, Eyewitness

Bloody Sunday: The Truth) helped significantly in persuading Tony Blair

to open his new Inquiry. With Mullan and with other witnesses I met, I

repeatedly found a (for me) unexpected bond. Sudden kinship would develop

with each encounter. Exchanges like "Where were you?

Sure, you must have been just 30 yards from me!" echoed among us. And we

often turned out to share an onerous sense of having unaccountably -- even

somehow unjustifiably -- escaped while others died. But "survivor

guilt" was a phrase that hadn't even occurred to me until it was voiced

by Mullan, who had been (we figured) about 25 yards from me when the shooting

started. Another fellow-witness, Derryman Terence McClements, who had been 17

at the time, said: "My instinct for self-preservation took over and I

ran. I've felt guilty that a fella I knew, two feet from my shoulder, was

shot -- and why was I not shot?" How might such feelings have played out

in my life? I still didn’t know – until, curiously enough, I was in Chicago,

and got thrown a question I wasn’t prepared for. I was taking part in a panel

discussion on the documentary, when I was asked: "What effect has Bloody

Sunday had on your reporting work?" And suddenly it tumbled out. I am by no

means a mass-murder specialist – God forbid – but the record is very telling.

I’ve written in print and for the screen about flower-shows through to summit

conferences, but there is – I realized that evening - an undeniable thread

woven through it all. There I am in 1974, embroiled in

controversy in the pages of The Times of London over Portuguese

colonial soldiers having mown down residents of Wiryamu, a remote village in

Mozambique – a massacre that gained little coverage in the US, although Time

magazine did briefly make a comparison with the 1969 My Lai atrocity in

Vietnam. And I’m on British television pointing

out frame after condemnatory frame of footage that captures South African

policemen firing at schoolchildren during the Soweto uprising of 1976. In the

1980s, for a television history of South Africa’s long struggle, I’m

reconstructing the Sharpeville shootings of 1960, when 69 unarmed anti-apartheid

protestors were gunned down by police. By the 1990s my first national

television documentary in the United States is the (then little-known) story

of a rampage by a KKK-inspired lynch-mob in 1923 that wiped out the

African-American community of Rosewood, Florida. Like it or not, aware of it or not, I

have clearly been drawn back again and again to the haunting narrative of a

powerful, armed group of men taking - initially with complete impunity - the

lives of ordinary citizens. Then finally in the 2000s I am back in

Derry, a citizen myself - not a journalist at all, and using none of the

paraphernalia of a journalist’s craft. I’m a man in a witness-box, telling –

in the face of whatever uncertainties and complex feelings may have

intervened - simply what he believes happened a long time ago. |

|