|

†††††††††† The Age of

Winchell By Ralph D. Gardner |

|

|

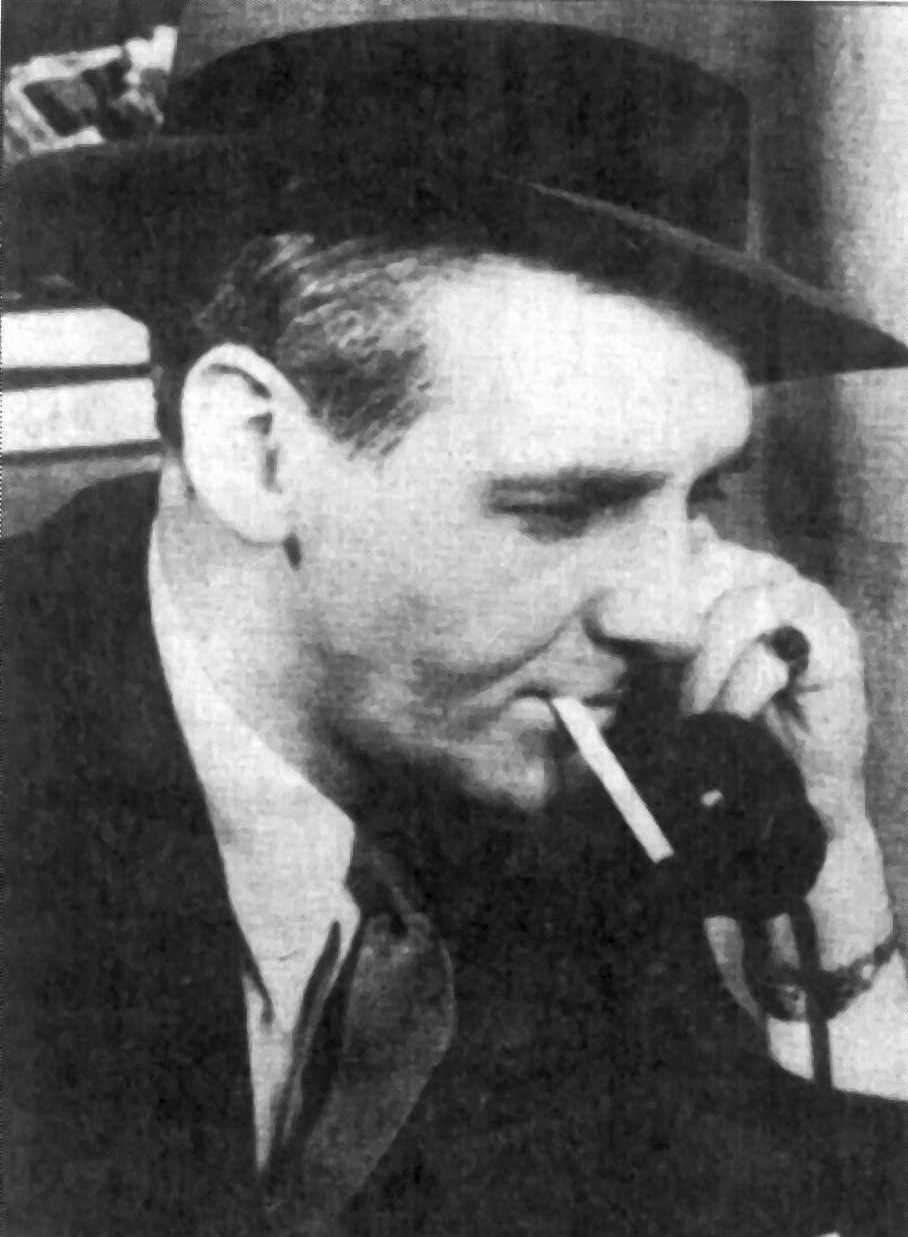

Walter

Winchell in his glory days, 1931. |

His virulent support of

Senator Joseph McCarthy, above, brought down the all-powerful Walter

Winchell. |

|

By Ralph D. Gardner Since retiring I occasionally lecture as

a visiting professor of journalism. At When I said I knew Winchell someone

asked: "Winchell who?" But from the 1920ís through the 50ís,

virtually everyone in During that time Winchell had imitators,

but no equals. And although his years of glory are not that long past, he is

today largely forgotten, except by an aged circle of what, in his day, was

called "Broadway press agents," by readers who once adored him and

by a now diminished handful of old newspapermen. Born in Starting during the Jazz Age, he wrote

six fast-paced columns each week (printed in nearly 2,000 newspapers), and in

the 30ís added Sunday radio broadcasts. Combined, they reached 50 million

homes. Feeding the publicís craving for scandal

and gossip, he became the most powerful -- and feared -- journalist of his

time. His articles were loaded with snappy, acerbic banter. Broadcasts were

slangy, narrated with machine-gun rapidity, a telegraph key clicking in the

background. "Mr. and Mrs. North and The columns, written in his own style,

were composed of short sentences connected by three dots. Fed by press

agents, tipsters, legmen and ghost writers, he possessed the extraordinary

ability to make a Broadway show a hit, create overnight celebrities; enhance

or destroy a political career. J. Edgar Hoover supplied scoops and favors in

return for Winchellís support. The workaholic Winchell was first to

announce big-name marriages and divorces, Hollywood romances, exploits of

socialites, international playboys, debutantes, mobsters and chorus girls,

plus latest reports of cafť society antics. He would also give timely plugs to

show-biz unknowns or has-beens who were sorely in need of a helping hand. At

the same time he savaged any whom he perceived to be his enemies. Throughout the Depression he was a

defender of the downtrodden. He backed President Roosevelt during those hard times

and throughout World War II. He became a cheerleader for our armed forces.

His slashing attacks upon Former speakeasy owner Sherman Billingsleyís

Stork Club became Winchellís base of operations. There, at table 50 of the

exclusionary Cub Room, he held court, receiving film stars, politicians and

others whose names often were known because Winchell ignited and sustained

their fame. He was besiged by press agents whose

ability to get a name into his column was worth pure gold. It secured new

clients. Some were hired primarily for their access to Winchell. In return for a blurb, most of them

regularly contributed repartee and quips that contained no mention of their

own employers. Some were said to compose for him entire columns in Winchellís

jargon. I cannot remember when I began reading

Winchell, but it was while I was very young. During World War II, when I

spent some months at the Armyís However, it was at Lindyís, close to Lindyís, for decades a Broadway mecca

and the setting for many of Damon Runyonís fables of mostly softhearted tough

guys and their flashy dolls, was filled day and night. Customers lined up for

overstuffed sandwiches (for which loaves of rye bread were sliced lengthwise)

and gargantuan wedges of strawberry-topped cheesecake. It was during 1947 or í48, when I was 24

or 25, a couple of years out of the Army and working several blocks south at

the New York Times. First editions came up from the basement

presses at Owner Leo Linderman -- Lindy -- always

had a table for us in the section that, well into early morning, was occupied

by newspeople, press agents, racetrack types and assorted Runyonesque

characters who eventually disappeared (as did the original Lindyís) when that

neighborhood ceased to be The Great White Way, where the action was, all day

and -- especially -- all night. Often Winchell appeared, accompanied by

a celebrity and one or two big fellows who I was told were bodyguards.

Winchellís eyes darted all over the restaurant and frequently he paused to

talk with those he knew. On the evening Iím now trying to recall,

I was seated with a press agent and two Times colleagues. One

moonlighted for Variety as a reviewer of nightclub acts.The other was

Sam Zolotow, the Timesí legendary theater news reporter who, with an

inch of cigar clenched between his teeth, looked and spoke like someone out

of a Runyon yarn. Years earlier Sam had earned enormous respect and a place

in show business llore as the only person who ever persuaded Florenz Ziegfeld

to repay to him borrowed cash. Sam never revealed how he did this. The room suddenly became hushed and

heads turned toward the entrance to see Winchell. He was leading his

entourage to our table for a few words with Zolotow who introduced me to him

as a fellow Times man. As I appeared younger than my age,

Winchell looked at me, puzzled, and asked if I was a copy boy.

"No," Sam told him, "heís an editor. Winchell (I always called

him Mr. Winchell) seemed surprised and although he probably didnít

catch my name, thereafter greeted me either as Kid or The Boy Editor. But at

that moment folks wondered if I was someone important. A few weeks later he arrived with Bobby

Ramsen, the Copacabanaís stand-up comic. They joined Jack OíBrian, Winchellís

pal and fellow Hearst columnist, who said he had just seen a musical in which

Ray Bolger did his trademark soft-shoe dance. "Hell!" Winchell exclaimed,

"Thatís what I did years ago in vaudeville," and he proceeded to

entertain diners with an agile routine that drew appreciative applause. After that period I rarely saw Walter

Winchell because in 1949 I was assigned to the Times bureau in He gave my item a whole paragraph. It

was unusual for anyone to leave the warm, one-big-family atmosphere of the Times

of those days (Editor & Publisher reported my departure in an

article with a headline that stretched across the top of a page). Winchellís

mention helped me land two of my first accounts. And for his kindness I owed

him everlasting thanks. In the 1950ís Winchellís direction took

an odd turn that was distressing to millions of readers. He became a

supporter of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, filling his pages and broadcasts with

vindicative, denunciatory tirades and mean-spirited accusations that resulted

in lawsuits and loss of media outlets. He had climbed to the top and tumbled. For more than three decades his name was

a household word. But like many of those he boosted to fame, he faded into

oblivion. Nervous breakdowns followed, as did eventual isolation. Movie

audiences recognized as Winchell the destructive gossip monger portrayed by

Burt Lancaster in the 1957 film, "The Sweet Smell of Success." Upon his death in 1972, a front-page

obituary in the New York Times eulogized Walter Winchell as "the

countryís best-known, widely read journalist as well as its most

influential." Neal Gabler, in his definitive,

sometimes searing biography, (Knopf, 1994) wrote that one of the saddest

aspects of Winchellís reign was his belief that it would never end.

"Celebrities, like other commodities, have a built-in obsolescence. They

take the national stage, do their act and leave." What was so unfortunate, a longtime

friend of Winchellís noted, was that he stayed around too long. _______________________________ Ralph D. Gardner is a former New York

Times editor and host of a talk show on books. |

|